People look up as a C-130 aircraft flies over the World War II Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial situated above Omaha Beach during the 77th anniversary of D-Day in Colleville-sur-Mer, France, June 6, 2021. (CNS/Reuters/Stephane Mahe)

From Homer, to the World War I poets, to the novelists of Vietnam, chroniclers of war are alert to the dangers of glorification. This Memorial Day, it's good to ask why.

Perhaps no conflict in American history has been more prone to such dangers than World War II, fought by the "Greatest Generation." In World War II Memoirs: The European Theater, the Library of America has compiled a collection of five veterans' voices; Charles B. MacDonald ("Company Commander"), Elmer Bendiner ("The Fall of Fortresses"), J. Glenn Gray ("The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle"), Mary Lee Settle ("All the Brave Promises") and James Harden Daugherty ("The Buffalo Saga") are all sensitive and perceptive observers, adept in examining the deeply complex and ambiguous nature of war — yes, even "The Good War."

Part of that ambiguity is due to the elusive nature of memory itself. The American novelist Wright Morris, quoted in Paul Fussell's 1975 The Great War and Modern Memory, said anything processed by memory is a kind of fiction.

In her insightful introduction to the volume, editor Elizabeth D. Samet suggests that "every narrative of remembrance works some violence on the facts for the sake of coherence; every memoir is a careful negotiation between past and present, between the actor embroiled in war and the narrator who somehow survived it."

The five authors all had survival in common, of course. They lived to tell their stories. But it is gratifying that their differing experiences make for an unusually rich volume that should be commended for its willingness, as Samet notes in paraphrasing Settle, to focus on some of World War II's "small, poorly lit corners."

Settle's memoir is the most inter-cultural and inter-national. An American who was married to a British citizen, Settle volunteered for the British Women's Auxiliary Air Force, or WAAF, working mainly in an airfield control tower.

A profoundly gifted writer, Settle chronicles the dull "grayness" of war in an engaging and arresting way. "For every 'historic' event, there were thousands of unknown, plodding people, caught up in a deadening authority, learning to survive by keeping quiet, by 'getting by,' by existing in secret, underground; conscripted, shunted, numbered."

If much of the memoir is taken up with the "gray days" experienced by Settle and her fellow WAAFs, Settle is also alert to war's shock and dangers, menace and ironies. In one masterfully understated description, Settle, on night duty, finds herself on the fog-obscured airfield of her air base. Something "like a football" brushes up against her leg. It turns out the object is the decapitated head of a man who, while refueling a plane, had slipped on the craft's wing and fallen into the propeller. Later safely inside, Settle learns what had "bounded past" her. She drops to the floor, sick and shattered.

British Women's Auxiliary Air Force members stand during inspection at a Royal Air Force base in England in 1942. (Wikimedia Commons/Public domain/Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer)

Of all the memoirs, MacDonald's is perhaps the most traditional and straightforward, vividly chronicling the challenging experiences of the foot soldiers, the GI Joes. But MacDonald, an infantry captain, also writes sensitively of the liberation of Czech areas once under German occupation.

"Suddenly, I began to realize what no one had thus far been able in the war to put into words — what we were fighting for," he recalls. "And I found a lump in my throat which I could not swallow."

MacDonald's heartfelt observation affirms the standard American narrative of the European war, and should not be downplayed. But in an interview, Samet cautioned that we should not fail to recall "the indifference of many Americans toward European freedom and especially toward the fate of the world’s Jews" prior to the 1941 U.S. entry in World War II.

That points to startling undertones of a troubling cast, particularly in Bendiner's work.

Bendiner's reflections and assessment of the use of American air power against German civilians are nuanced and often critical. A member of a bombing crew, Bendiner says the Allied war against Germany was assuredly just. But he also muses about what he calls a "dangerous kind of bookkeeping" and a "terrible and Godlike arithmetic" in the bombing of civilian population centers.

He also relates a telling incident of prejudice at the end of the war. Over drinks, a military information officer thanks Bendiner, who was Jewish, for his service — but ends up offending him. "You made it all the way," the man says. "Not many of your people stick it out."

A startled Bendiner walks out of the bar and later reflects that living in the "same century as Auschwitz, I ought not to mention my little encounter." Still, the incident rattles him. "(It) would have left no mark on me," he writes, "if I had not been rendered so vulnerable by a false sense of security derived from the battlefield where death creates the splendid illusion of brotherhood."

'In order to survive this time I must love more. There is no other way.'

—J. Glenn Gray

Such "illusion of brotherhood" was no stranger to Daugherty, who chronicles his experiences as a member of the only African American infantry division in Europe. As the last piece in the collection, Daugherty's memoir ends in a forward-looking way, with an epilogue that takes the reader into the cherished early days of Barack Obama's presidency.

Doughtery, who died in 2015, proudly hails that landmark as something he and other African American World War II veterans helped usher in. But earlier, in recalling a visit to Washington, D.C., that he and his soldier friends took at war's end, he addresses white America in words that are strikingly prescient for today.

"To you our big fertile country we say: our eyes are wide open. We are looking to see your freedom." Will he and his fellows see the "the winds of freedom, " or "the sands of humiliation?" More pointedly, Doughtery asks, "Will it be that we fought for the lesser of two evils? Or is there this freedom and happiness for all men?" He concludes, "Answer us, our big fertile country! Answer us! Answer us."

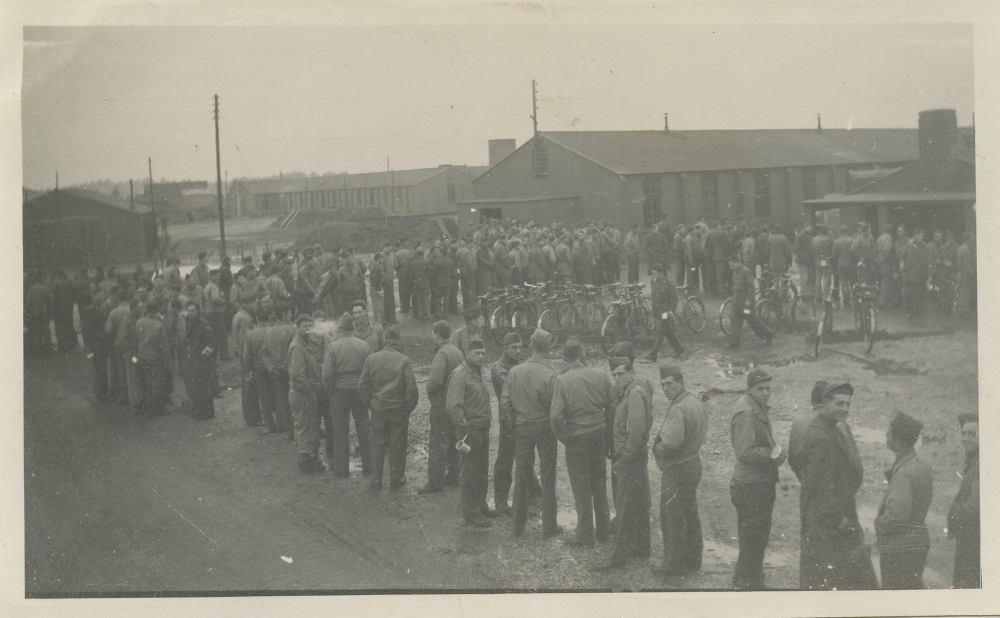

American soldiers stand in line waiting for food in December 1943 in England. (Wikimedia Commons/CC0/Anonymous-Froggy)

If that unsettles the reader, so does much of Gray's work, the one that is perhaps hardest to classify. Gray, who served as a counterintelligence officer, was drafted on the very day he learned he had successfully completed his doctoral work at Columbia University.

Gray crafted a hybrid work of meditations on the nature of war and excerpts from a diary kept during his service. Both elements are moving — though read now, some of Gray's meditations feel a bit dated, particularly in a section focused on battle and eros, as recent feminist scholars have added new and welcome insights about war and gender. Meanwhile, Paul Fussell's landmark study helped shed new and welcome light on homoeroticism and war, a topic Gray avoids. But those quibbles don't take away from Gray's considerable achievement.

Advertisement

At one point Gray comes to realize "with a kind of horror that I was becoming inured to cruelty and not above practicing it myself on occasion." In a moving reflection on the "ache of guilt," Gray speaks of how his interrogation of an elderly Gestapo agent may have contributed to the suicide of the man and his wife.

Gray writes in his diary of laying awake at night, thinking of "all the inhumanity of it, the beastliness of the war." He rose one morning in December 1944 "tired and distraught," "caught in an evil time" and knowing "that in order to survive this time I must love more. There is no other way … "

In a volume of strikingly rendered examples of "literature of catastrophe" by five gifted American World War II memoirists, that word "love" practically jumps off the page.