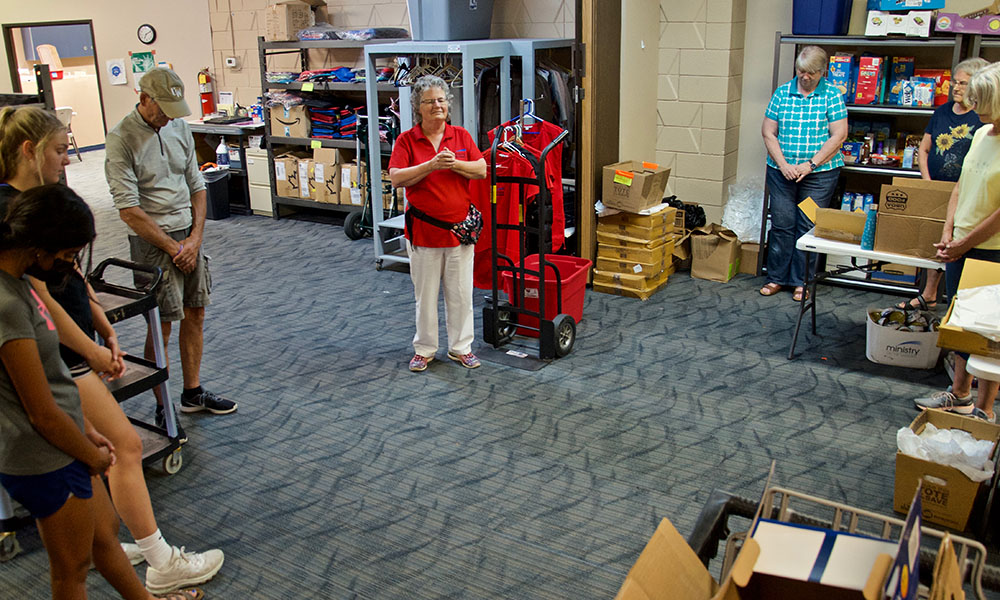

Volunteers hand out food during the twice-weekly food pantry at Ministry on the Margins in Bismarck, North Dakota. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Editor's note: The phrase "just transition" is part of the growing lexicon about moving from an economy based on fossil fuels to clean energy. But this phrase's meaning varies. The term can also mean the need for a just transition to new jobs for those employed in industries such as mining. Catholic sisters are involved along the spectrum of transition efforts.

Global Sisters Report presents this series as world leaders, climate experts and activists gather in Glasgow, Scotland, for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP26. The Oct. 31-Nov. 12 conference is expected to establish new international targets for reducing harmful emissions caused by fossil fuels.

Benedictine Sr. Kathleen Atkinson looks over the area outside the Ministry on the Margins building, where the hot sun still beats down but shadows are growing longer as the afternoon turns to evening.

In the parking lot, people who have been outside all day are grateful for popsicles, while others take a cup of hot coffee. Families carry away bags of groceries to beat-up cars or to mobile homes in dirt yards across the street. At the door to the building, people request personal items such as hygiene products and toothbrushes, which are retrieved by volunteers. On the sidewalk, parents choose from boxes of grocery items and produce while they hold babies or hang on to children.

In the first hour of today's twice-a-week food pantry, 66 households have already been served, and people are still arriving on foot, on bikes, and in cars and trucks. Ministry on the Margins serves about 1,000 people a week in Bismarck, a tiny fraction of the more than 37 million people living in poverty in the United States in 2020, according to the latest Census figures.

The need in the region has increased dramatically since the start of the pandemic, Atkinson says. Even in an area where jobs are plentiful, many were laid off during the extended lockdowns, homeless shelters closed and jails released inmates.

"They were trying to stop the spread of the virus, but no one was asking where these people were going," Atkinson says. "We were locking ourselves in, but there's all these people that were locked out."

Making sure people aren't locked out as the economy changes from being based on fossil fuels to more sustainable forms of energy is one of the keys in a "just transition" to clean energy. Even as world leaders, experts and activists convene for COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, to try to hammer out ways to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis, places like North Dakota are grappling with how to handle the effects of an oil boom while laying the groundwork to tap other forms of energy.

There's a lot at stake. The U.S. Department of Energy reports there were 8.4 million people employed in the energy industry in the country in 2019. The downturn in the economy caused by the pandemic cost the industry 1.4 million jobs in the first half of 2020, though 560,000 of those were added back by the end of the year, the Department of Energy reported.

There are already millions of people struggling in the current economy. Some fear a sudden shift away from a petroleum-based economy — without proper job training and alternatives — could shut out millions more.

"People are already being left behind" even in a booming economy by a lack of education, job training, transportation, child care or health issues, Atkinson says. "That's our people here. They're long-term stressed."

Snow globes for sale in the Fargo, North Dakota, airport gift shop highlight the state's oil industry. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

So how do we change our economy without leaving millions of people out of work? How do we transition to sustainable energy in a way that is just and benefits more than just those making capital investments?

"We're looking at how to properly manage the energy transition to renewables and ensure workers and communities are not left behind in that transition," says Stephanie Lavallato, associate program director for climate and environmental justice at the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility, which lobbies corporations on social justice issues. "Often companies do not include these stakeholders by default."

A just transition to a sustainable economy has become one of the group's focus points.

"We need to make sure that those most impacted are front and center in any transition process," she says. "We're still very far from that."

The Sacred Heart Benedictine Monastery in Dickinson, North Dakota, has a framed photo of the community's former convent, which had the first commercial wind turbines in the state. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

One hundred miles west of Bismark, Benedictine Sr. Paula Larson has seen that it is possible: The end of the North Dakota oil drilling boom has been eased somewhat by the growth of sustainable energy, a field the Benedictines were pioneers in.

In 1996, the Sacred Heart Monastery near Dickinson began operating the first two commercial-sized wind turbines in North Dakota, generating enough electricity to cut the convent's energy bills in half, and providing a platform to educate thousands of high school students on field trips about sustainable energy. "We were the pioneers," Larson says. "It was quite a challenge, I tell you, to get hooked up to the utility, but now they own turbines themselves."

Larson said the growth of the sustainable energy industry in North Dakota has definitely helped ease what could have been an economic disaster for the region when oil drilling slowed dramatically.

"I heard on the news today there are more job openings in sustainable energy than there are in the fossil fuel industry," Larson says. State officials said there were more than 18,000 job openings in North Dakota in October.

Benedictine Sr. Paula Larson holds a photo of the community's former convent, which had two wind turbines, the first commercial wind turbines in North Dakota. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

The Department of Energy says there were about 100,000 jobs in the wind industry nationwide in 2020. Even as hundreds of thousands of jobs in the traditional energy industry were being lost during the first year of the pandemic, the number of wind generation jobs grew by 2%, and jobs producing hybrid vehicles grew by 6% and jobs building electric vehicles by 8%.

In December 2019, the Bismarck Tribune reported there were more than 1,700 wind turbines in the state, double the number in 2010. From 2010 to 2018 wind energy went from providing 12% of the state's power to 25%, while coal's share dropped from 82% to 65%. All while an oil drilling boom in the Bakken oil fields of western North Dakota came and went.

Geologists had long known there was oil beneath western North Dakota, but it wasn't until the early 2010s when companies began using hydraulic fracturing (known as fracking) that it was accessible. An oil boom followed: "Oil production soared from 236,000 barrels per day at the start of the decade to 1.5 million barrels per day by the end," the Tribune reported.

McKenzie County's population more than doubled from 6,360 in 2010 to 14,704 in 2020. During the most frenzied part of the drilling boom in mid-decade, "man camps" were set up to house the thousands of men who came to work in the oil fields. Crime, prostitution and other social ills soon followed and the police force was overwhelmed.

Wind turbines that are part of the Bison Wind Project west of Bismarck, North Dakota. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

About the time the county began to catch up with the infrastructure and service needs of its new population, the drilling boom ended, and many of the jobs drilling new wells disappeared.

But while most of those jobs were gone, there was still a need for people to maintain all the wells that had been drilled and were now pumping oil. There was also the trucking industry needed to carry the oil, pipelines to be built, and equipment to be repaired.

"The fracking crews — which are transient anyway — they left, but the crews to run the wells stayed," Larson says. "There were so many jobs available the minimum wage hasn't affected us for probably the last 10 years."

Most oil wells also produce natural gas, and in the boom period most drillers didn't bother trying to capture it — instead burning it in gas flares. Once drilling slowed, there were jobs created installing equipment to capture the natural gas so it could be sold and used instead of wasted. When the coronavirus pandemic brought the economy to a halt and oil prices plummeted, people were hired to seal up abandoned wells that were no longer producing. Those long-term jobs brought not just workers, but their families, which created more jobs to serve them.

There were construction jobs to build infrastructure such as highways and water treatment plants, new schools, new houses and apartment buildings and businesses, and jobs working in the new schools and businesses and health care. The number of new housing units under construction in the oil-producing counties went from less than 500 a year to more than 4,000.

"Every town [in the oil region] has had to build new schools," Larson says. "The fastest-growing part of our population is people under 18. …There's been a tremendous baby boom."

Railroad tank cars wait to be filled with ethanol at the Red Trail Energy plant in Richardton, North Dakota. Some of the jobs lost when the oil drilling boom ended in North Dakota have been made up for with growth in areas such as ethanol production and wind farms. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

There is also the booming wind energy industry, and ethanol plants popping up to make cleaner-burning gasoline from corn. The five ethanol plants currently operating in the state produce a half-billion gallons a year, a five-fold increase from 10 years ago. Some ethanol plants are now looking to capture carbon dioxide and store it underground where it can't cause the atmosphere to warm.

Larson said the wind turbines cut the convent's electricity bills in half and paid for themselves in about seven years. They operated the turbines about 20 years before moving to a much smaller, more centrally located convent in Dickinson.

To see what happens without a just transition, simply look to West Virginia.

Wind turbines along Interstate 94 west of Bismarck, North Dakota (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

At its peak in 1940, there were 130,457 people employed in the state's coal mines. But as demand shifted to lower-sulfur coal from western states, workers were replaced by machines and the industry adopted surface mining, which requires far fewer workers than underground mines, the jobs disappeared. In 2020, there were 50,089 jobs in the state's coal industry, and only 11,646 of those were at the mines themselves.

The contrast is stark: U.S. News & World Report says for 2021 North Dakota ranks No. 27 among states in health care, No. 25 in education, No. 32 in economy and No. 4 in infrastructure. West Virginia, meanwhile, ranks No. 47 in health care, No. 45 in education, No. 48 in economy and dead last in infrastructure. North Dakota ranks No. 11 in employment, West Virginia is No. 48.

St. Joseph Sr. Gretchen Shaffer who ministers in Kermit, West Virginia, said one of the local mines closed recently, cutting not only the high-paying mining jobs, but truck driving and related jobs, as well. It is just the latest economic blow to a state that has suffered them for decades as its coal mining-based economy died.

"It's hit this community hard," she says. "We're happy to have less mining because of climate change. We have to stop burning coal. But we also need alternatives."

With no transition, there is little hope.

"Lots of young men just finished high school to go into the mines and earned a very good salary. They could make $45-$50,000 with almost no formal education," Shaffer says. "Then they're laid off in their late 40s or 50s. They can't sell their houses and move — nobody wants to buy their home. There's talk about retraining, but it's a fluke if a man comes out of the mines and gets a job. What can you train them for if there's nothing else?"

Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility's Lavallato said it's important to remember corporations have to answer to their shareholders, and change is never easy.

"They're not planning to ruin the world or peoples' lives, but there's constraints they face," she says. "And in the case of big energy utilities, they're not designed to be nimble or fast. In these dialogues, it's a very big learning experience both for the investors and the company."

Advertisement

Sr. Susan Mika, from the Benedictine Sisters of Boerne, is the director of the Benedictine Sisters' corporate responsibility program in San Antonio, Texas, and works with the Benedictine Coalition for Responsible Investment, a coalition of 24 Benedictine monasteries and the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth, Kansas.

She says the widespread blackouts Texas experienced in February as a winter storm froze energy production as demand surged, overwhelming the state's electric grid, shows we cannot continue with business as usual. Millions were left for days without power.

"[Corporations] know things are changing," Mika said. The key is ensuring the transition happens in a just way, not in whatever way most benefits shareholders.

Mobile homes bake in the summer sun across the street from the food pantry at Ministry on the Margins in Bismarck, North Dakota. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Back in Bismarck, Atkinson sees on a daily basis what happens when people are left behind, even in a booming economy. She tells of a couple with eight children living in a single-wide trailer. A farm family that moved to the city to be closer to medical care now has no income and is living in their car while the father gets chemotherapy. Migrant workers who travel to harvest crops only to find a drought has left them out of work and with no gas money to return home. The maitre d' of a fancy restaurant comes to the food pantry because the restaurant closed under coronavirus restrictions.

Even the social safety nets have holes, she says: Food stamps are great but can't be used for essentials like toilet paper.

When she asks a client how they're doing, the response is brutally honest but hopeful. "Kind of miserable," the woman says, "but I got to work a little today."

Atkinson's admiration for the people she serves is obvious.

"They're the survivors," she says. "I've found my people."