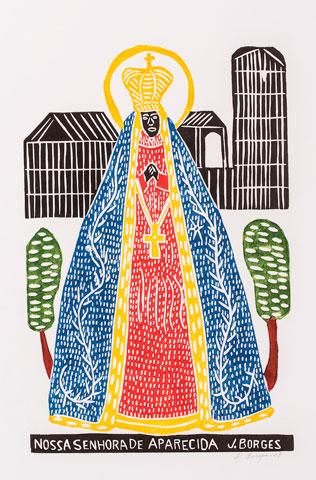

"Our Lady of Aparecida, Patroness of Brazil" by José Francisco Borges (Paul Primeau)

From the outside, South Africa's largest Roman Catholic church, Regina Mundi (Queen of the World), looks rather generic -- at least to the extent that a church can when it is set in the township of Soweto, not far from houses whose roofs are secured by rocks.

Inside, Laurence Scully's "Madonna and Child of Soweto" -- often called the "Black Madonna," although the Christ Child is also black -- leaps off the wall. Two forks and a machete, mapped out over Soweto's houses at the bottom of the work, symbolize the people of Soweto's suffering, per the church website.

Elsewhere in the church is a sculpture of Our Lady of Aparecida, based on the 18th-century Nossa Senhora Aparecida in São Paulo, Brazil. The depiction of the Virgin Mary, widely held to be Brazil's most important after three fishermen discovered it under miraculous circumstances in 1717, also has black skin. That tradition dates back to the Middle Ages, but when the sculptures are located in a contemporary context -- particularly slavery and oppression in South Africa and in Brazil -- they are all the more striking.

The latter country is the subject of the exhibition "Bandits & Heroes, Poets & Saints: Popular Art of the Northeast of Brazil" at American University's Katzen Arts Center in Washington, D.C. (through Aug. 14), an exhibit that features its own Lady of Aparecida.

The undated woodblock print by José Francisco Borges shows her in a long blue and red robe with gold trim, her hands clasped in prayer above a dangling cross. Flanked by two trees, she wears a crown with a cross upon her haloed head, as she stands in front of a structure, perhaps a partial representation of São Paulo's Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady Aparecida.

Although the work represents the protection of the oppressed, it is regal and uplifting in its palette and treatment. Like many of the works that hang in the exhibition's display cases and on temporary walls, it is colorful and lively. But as visitors meander through the exhibition and take a closer look, the joyful gives way, in certain places, to the difficult and challenging.

In a section on slavery in Brazil -- where 45 percent of the 11 million African slaves imported to the Americas from the 16th to the mid-19th centuries arrived to work sugar plantations, according to the catalogue -- a wooden figure in a cruciform position hangs on the wall. Metal chains shackle the wrists and legs of the man depicted in "Untitled (Enslaved Man)" (1994) by Louco Filho.

The sculpture reflects both African and European influences, a wall label reveals, and it ties the Crucifixion to suffering slaves. Ultimately, the label suggests, the figure's uplifted arms, posture and gaze "suggest a strength and spirit stronger than the chains."

Alfredo Cruz's painting "Untitled (Slave and Slave Driver)" (1993) shows five black slaves working a field, while a white man leads a horse with one hand and prepares with the other to strike a black slave. Tied to a tree, the latter's pants hang at his knees, and red gashes already crisscross his head, back and buttocks.

The slave's nakedness, and the other slaves' half nakedness, starkly contrasts with the slave driver, who wears a hat, boots with spurs, a knife on his belt, and a vest. A dog relaxes at his feet. Part of the horror is that from some perspectives all seems well in the world -- at least the dog's -- while mere inches away, atrocities transpire.

Where the exhibit exposes disturbing racial oppression, it also highlights religious tolerance between Catholics and adherents to African faiths in Brazil.

"It's fascinating to see what kind of syncretization goes on, and how the images can work for saints and gods. That translation between the two is awfully intense," Jack Rasmussen, the Katzen Center's director and curator, said in an interview. "On the surface, you can't think of anything more different, but there's a wonderful correspondence. It gives one pause that maybe there is some kind of universality."

Franklin Silva Netto, who has worked at the Brazilian embassy in Washington for two years, agreed.

"The Catholic religion was present in our history since the very beginning," he said in an interview. "The first official act in Brazil was a Catholic Mass."

Catholicism in Brazil has been very inclusive, he added, and African religious traditions and Catholicism meld in unexpected ways.

"They never fight each other. Actually, they are two layers of the same phenomenon," he said. "In Brazil, the Catholic religion was always mingling and always having a dialogue."

In Brazil, where the largest number of Catholics in the world live, there are mappings of African deities upon Catholic ones, and adherents are comfortable with the hybrids. "They are real Catholics, but at night they go to places where they worship deities from Africa," Netto said.

That's been the experience of the exhibition curators, Marion Jackson and Dominican Sr. Barbara Cervenka, as well. The two estimate they've visited Brazil about 20 times since 1992. Starting in 2000, they traveled more broadly in northeast Brazil, a part of the country that is much less known to foreigners than the south and the Amazon. In the northeast's small villages and towns, the two were enchanted by what they found.

"This show is made of the materials that are at hand. Nobody had much money for buying supplies," said Jackson.

The two made a special effort to avoid touristy hotels, to learn the language, and to make friends with locals. That brought them to ceremonies of the Candomblé faith.

"They're very, very different, and at the same time, there was a familiarity about them," Cervenka said. "There's a kind of formality in them -- a kind of ritual that would not be unfamiliar to people from Catholicism."

Candomblé was forbidden until the 1970s, so it came to incorporate elements of Catholicism alongside West African traditions. If one goes to a religious goods store in Brazil today, according to Cervenka, one is likely to see sculptures of St. Barbara that are connected to a thunder and lightning god, or an orisha named Shango, and images of Mary alongside "a rather lascivious-looking mermaid" called Yemoja.

"There are millions of St. Georges, and they are slaying all kinds of dragons, but it's really Oshosi, the god of the hunt, that's being celebrated," Cervenka said.

There have been, and remain, purists on both sides, who would rather see Catholicism and West African traditions stay distinct for a variety of reasons, Cervenka said. But perhaps most surprising to viewers will be the ways that the two can share the same sacred space. That, as well as the region the exhibit focuses on, charts untrodden ground, said Netto.

"Brazil is a very famous country," he said. But reducing Brazil to the Amazon region and to the touristy cities of the southeast would be like thinking of the United States as just New York City and the Grand Canyon.

"This Brazil will be a surprise for many Americans," Netto said.

[Menachem Wecker is co-author of the book Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]