Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards volunteers in the water drop-off ministry in the Sonoran Desert near Ajo, Arizona. (Peter Tran)

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards is vice president of the Aguilas del Desierto (Desert Eagles), a nonprofit that rescues and recovers men, women and children who are lost in the desert or mountains in California or Arizona while trying to cross the border into the United States. In 2021, volunteers of the organization rescued more than 183 people. They also began a yearly prevention campaign to encourage migrants not to cross the border.

Based in California, Edwards was in Arizona for a month from October to November to network with church and civic groups working in the border ministry. She joined for the first time Ajo Samaritans to drop off water, food and blankets in remote locations along migrant trails in the Sonoran Desert. Founded in 2012, the Samaritan group offers humanitarian relief to help those crossing the U.S. border survive threats from the external desert environment.

Edwards, who took her first vows as a Felician sister in 2014, has served at Holy Name of Mary College School in Mississauga, Ontario, and at the Angela Spirituality Center in Pomona, California. She talked with Global Sisters Report about her work with Aguilas and how she came to volunteer for the water drop mission with the Samaritans as well as her volunteer time with the migrant resource center in Agua Prieta, Mexico.

GSR: You are working with Aguilas. How did you hear about the Samaritans?

Edwards: Aguilas del Desierto has a camp in Ajo for volunteers to stay when we conduct searches. Some of the Ajo/Tucson Samaritans have joined the Aguilas group for searches.

Advertisement

Why are you involved in the border ministry?

When I learned that many people were crossing and dying in the desert, I joined Aguilas to learn firsthand what was happening. It was hard to believe that so many people were dying and it wasn't on the news.

In my first search, we found the remains of a young woman and a little girl — only part of her foot in a shoe. I asked myself how this can be happening. How could it matter so little that it's not in the news?

As a sister, my heart was breaking because, regardless of who they are, they are loved dearly by God. They must have people who love them, families, children and dreams. From that moment on, I wanted to be involved to remember each one and to say, "This is not OK." No one should be dying because they hoped for a better life.

Tell us about your present ministry.

Even though I've been volunteering with Aguilas del Desierto since 2018, it was 2021 that I was appointed vice president of the organization. We are a search-and-rescue group that tries to help families find their loved ones who are missing along the U.S.-Mexico border.

At the border of the Tohono O'odam Nation in Arizona, Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, right, works with Officer Mario Agundez, founder of the Missing Migrant Program of the U.S. Border Patrol. Edwards is vice president of the Aguilas del Desierto (Desert Eagles), which has helped in the search, rescue and recovery of migrants in the desert and collaborates with the similar Border Patrol program. (Peter Tran)

Our group receives numerous calls or contacts every day from someone looking for a loved one. Sometimes, border-crossers themselves call in distress. Sometimes, someone reports seeing a body or knows that someone was left behind.

We conduct searches about once a month, not more often due to lack of funding. Our group is 95% volunteer, with our president receiving a small stipend. Our vehicles are about 20 years old, and we camp in the desert with a group of faithful volunteers. We believe that each life matters.

You must have seen many human remains in the desert.

Different moments have stayed with me as I've met migrants along the journey since 2018. I've seen skulls, bones and even a little girl's shoe with some of her foot still inside, but it wasn't until October 2018 that I helped the group recover the body of a young man who had been deceased for 24 to 48 hours.

A black empty water container was left by migrants after crossing the border into the U.S. from Mexico. Volunteers who do the desert water drop-offs for migrants pick up the empties as part of their work. (Peter Tran)

The group received a report of the location of a body that had been on the side of a busy road. His body had been stripped of anything that could identify him. As we approached the location, the smell was overwhelming. He was lying face up in a ditch wearing only pants and a bracelet with bright teal beads.

I couldn't take my eyes off his bracelet. He was no longer a body, but a man who had family and dreams. Maybe his girlfriend gave him that bracelet. Maybe his daughter. Maybe it reminded him of why he was risking his life. We'll never know.

On the way back to the Aguilas campsite, our president, who had seen many bodies himself, knew I was in shock. Quietly, he began singing a silly children's song ["Baby Shark"]. The tension broke, and a few joined in, quietly singing. It was the first time I understood how humor helps us hang on to a sense of humanity.

After recovering that young man's body, I realized how easy it would be to harden my heart, to insulate myself from so much suffering and death. God's grace enables me to continue to reach out with compassion and mercy and to let my heart be broken over and over again without destroying what makes me human.

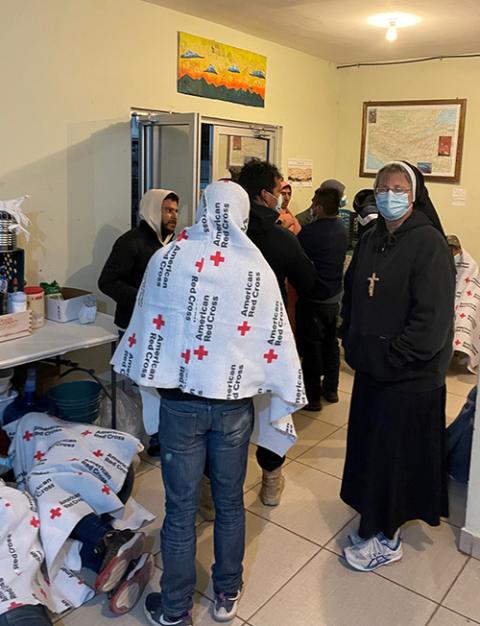

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, right, welcomes returned migrants to the Migrant Resource Center in Agua Prieta, Mexico. (Peter Tran)

What did you learn from your monthlong experience in Arizona?

I have a better understanding of efforts to respond to the crisis at the border beyond our search group. This year, I am researching ministries at the border for my community so that we might respond to what is happening.

Recently, I was blessed to volunteer at a migrant resource center in Agua Prieta, Mexico. Those returned to Mexico from the U.S. border walk from the bus through the gate to the welcome center, where they can rest, charge their phones, call loved ones and get something to eat.

As each group lined up, I couldn't help but notice how cold they were. Many only wore a thin T-shirt and jeans. They eagerly reached for the hot coffee we offered but were shaking too hard to pour sugar into the cup. We couldn't pass out blankets, hats and sweatshirts fast enough. They were visibly discouraged, often injured, and maybe not even sure where they were.

I will never forget two women who approached for coffee, both very young. Clearly, the one woman was caring for the other, who could not stop crying. She cried very softly the whole time, and then they left right away. I wondered what trauma had happened to her and how much her life had changed.

After dropping off water on a migrant trail in the Sonoran Desert, volunteers walk back to their vehicles with empty water bottles in October 2021. (Peter Tran)

Later, a young man shared that he had to try to cross the border again. He said, "Here, I might make $10 a day, but on the other side, I might make $10 an hour. I have to help my family." I could see the desperation in his eyes. I thought any young person would do the same thing.

Another memory that stays with me are the people who couldn't walk because the blisters on their feet were so painful. The last day I was there, I helped to soak and bandage blistered feet for hours. They had blisters between their toes, on their heels, and one woman, the entire ball of her foot was a blister.

As I cleaned and sanitized their feet, putting on anointment and bandages, I couldn't help but think of Holy Thursday and Jesus washing the feet of the disciples. As I worked lotion into their dried cracked skin, I tried to pamper them a little and massage their feet as if to say, "You are still important, you will be OK."

One gentleman spoke softly and gestured to his heart. I didn't hear all that he said, but I understood he was grateful from his heart.

Sisters from various congregations have come to participate in the border ministries. What does that say about religious life today?

Historically, sisters go toward where there is suffering. We look to find our suffering Lord. It's where the Holy Spirit is moving most powerfully. Sisters are called to go, like a first responder, to where the suffering is, where hearts are crying. We are called to go there and lift it up. Lift up those who are suffering.

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards (in neon yellow shirt, seated in background) writes messages to migrants on water bottles with volunteers in the Sonoran Desert near Ajo, Arizona. The messages include the dates of the water drop and encouraging words, such as "Don't give up" and "God loves you," sometimes accented with a cross or smiley face. (Peter Tran)

I've grown to love my volunteer colleagues. Their heart, for those who are in distress and dying, inspires me. They help me stay focused in the midst of so much suffering and death. It is through them I have learned to respect those who are crossing the border and those who did not make it. I know Jesus loves them, and he must feel pain and sorrow for each one of them.

It's this understanding of how much Jesus loves them that helps me realize what it means to be a sister, to know Jesus' love and share it.

There aren't words or scenarios to justify what's happening at the border. My prayer for a long time had been, "Lord, break my heart for what breaks yours." Now that I've experienced some of the pain in his heart, I don't want to leave.

Nothing will convince me to see these border-crossers as anything but my brothers and sisters, deeply loved and cherished by God.