Sacred Heart Sr. Regina Martinez Méndez is at a loss to understand why young people in the colonia of La Chacra join gangs. "I've never understood why," Martinez said earlier this year on the eastern outskirts of the capital city of San Salvador, where she lives and works. (Chris Herlinger)

Why young people in the colonia of La Chacra join gangs is still a mystery to Sr. Regina Martinez Méndez, even after five years of ministering in the neighborhood on the eastern outskirts of the capital city of San Salvador.

"I've never understood why," Martinez said as she sat down at the dining room table of the small parish residence she shares with two other sisters of her congregation, the Apostólicas del Corazón de Jesús, or the Apostolic Sisters of the Heart of Jesus. On that afternoon La Chacra was quiet. But it is not unusual to hear gunshots on the streets of the colonia, which often reflects El Salvador's larger issues with poverty and violence.

In La Chacra, stories about bad decisions leading to tragedy are legion. They point to a serious social problem in a country still recovering from a calamitous 12-year civil war that ended in 1992, and in which gang violence is a daily threat.

Healing the wounds of violence and offering support for communities affected by gang activity are at the center of ministries like those of Martinez.

A poignant example of the outcome of gang life is the case of Juan (a pseudonym Global Sisters Report is using to protect his family). Martinez knew the 13-year-old when he was enrolled in a parish school run by the congregation in La Chacra. He was a typical kid — studying as best he could but maybe not with a full heart.

Not long after Martinez arrived in El Salvador in 2014, he told her that he had enough studying. Six months later, he disappeared, left home and joined one of the four gangs that rule the streets of La Chacra. "Suddenly, he had a gun, hung around these guys," she said in an interview earlier this year. "His mother tried to convince him not to do this. It didn't work."

Two years later, Juan was killed by police in a street skirmish. Martinez said police shot the youth thinking he was shooting at them when in fact he had been shooting at a member of an opposing gang.

"He suffered while he lived," Martinez said, reflecting on Juan's short life. "He was a hyperactive kid," she said, and that may have led to his being bullied by other boys. But whether that led him to join a gang, no one knows.

Outside the home shared by three Sacred Heart sisters in La Chacra, on the outskirts of San Salvador, an economically depressed area and vulnerable to violence; the late Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero is depicted on the street mural. (Chris Herlinger)

"At first, I thought it was because they are poor," said Martinez. "But since working here I've seen poor kids who've become doctors. I have no idea why some do that, and others join gangs."

Martinez smiled when recalling her congregation's decision to send her to El Salvador, because, she was told, she had the inner strength and fortitude for a difficult mission.

"They can't send just anybody here because of the intense violence," she said. "So they sent me."

Martinez is part of an initiative called the Color Movement, which has backing from the Minneapolis-based humanitarian organization Alight, formerly the American Refugee Committee, as well as Salvadoran and American business people.

The initiative supports sister-led programs for youth in challenging communities like La Chacra. Twelve sisters of different congregations work under the Color Movement umbrella and teach, mentor, engage with youths in after-school programs and offer pastoral support.

Such programs — small in scale, but rooted in the needs of affected communities — are a balm in El Salvador, where violence remains a daily challenge.

El Salvador was the second-most violent country in the world (after Syria) in 2016, and had the highest rate of any country of the use of firearms in at least 50 percent of deaths, according to a 2017 report on global violent deaths by the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey, which studies armed violence globally.

The presence of gangs is a key reason. Noting that gangs exert strong control over large areas of El Salvador, the New York-based monitoring group Human Rights Watch said in its 2019 report that the country last year had about 60,000 gang members spread across nearly all of the country's municipalities, 247 out of 262 total.

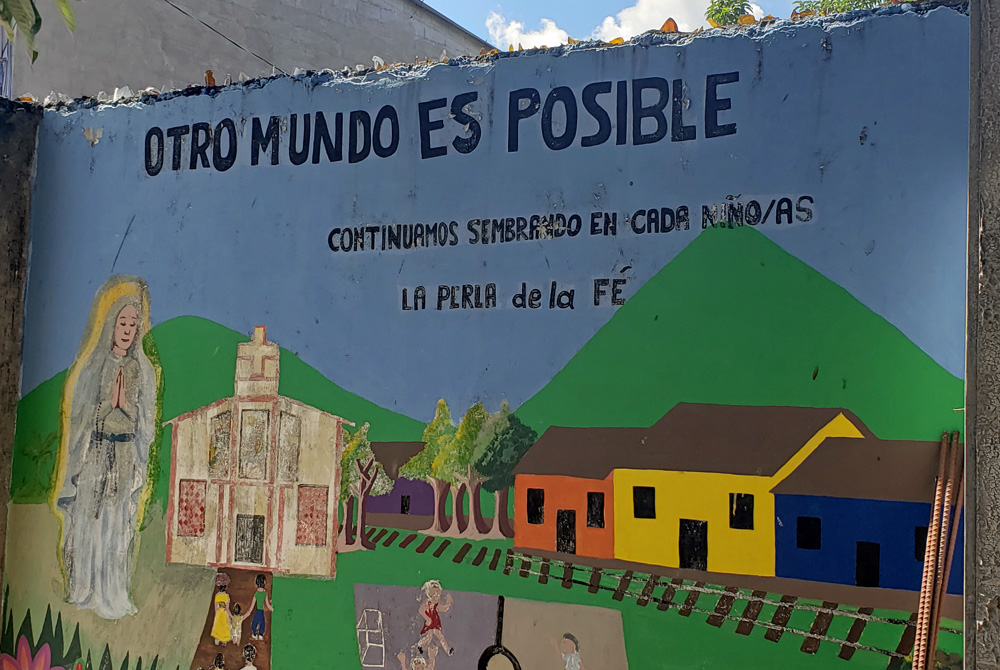

“Another world is possible” says this mural near a parish school and school rooms used for after-school activities and run by a group of Sacred Heart sisters in Chacra, on the outskirts of San Salvador. (Chris Herlinger)

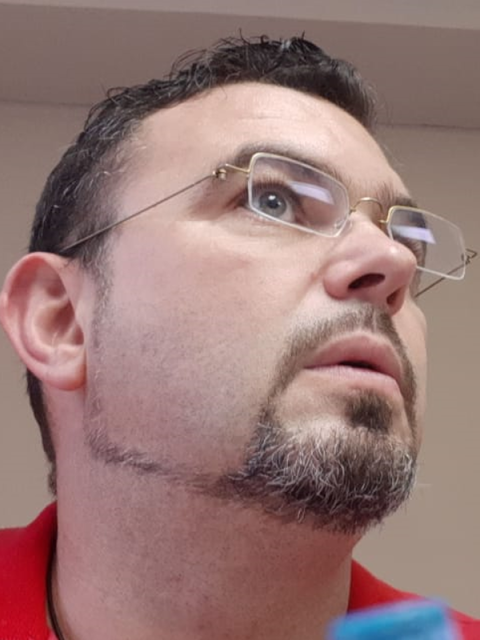

The ubiquity of gangs does not surprise human rights activist and former Passionist priest Antonio Rodriguez, originally from Spain but who now lives and works in El Salvador. The now-former priest's advocacy for the rehabilitation of gang members has proven controversial — and also landed the cleric briefly in jail in 2014 for activities that included bringing in cellphones to gang members in prison.

In an interview in San Salvador, Rodriguez, who describes himself now as a "secular priest" and is well known in El Salvador by the name Padre Toño, believes the lens through which the Salvadoran gangs are perceived is skewed. Efforts to humanize or reintegrate gang members are seen as threatening in what continues to be a war-like environment, he contended.

Adding to the problems were the deportations back to El Salvador of thousands of young people whose families had fled the war to U.S. in the 1980s and joined gangs in cities like Los Angeles, he said.

Human rights activist Antonio Rodriguez, a former Passionist priest but still well known in El Salvador by the name Padre Toño, says efforts to humanize or reintegrate gang members are seen as threatening in what continues to be a war-like environment. (Courtesy of Antonio Rodriguez )

In the face of these challenges, Salvadoran politicians of both the left and the right, Rodriguez said, have embraced the language of "punitive populism" to further their political agendas without getting to the root of the problem.

"Violence is not a security problem, it's not a problem of gangs by themselves," he said. "It's a problem of historic conflicts." The only dialogue now "is through bullets," he said, adding that in neighborhoods where gangs thrive, the only government presence is through a "very violent police force." Such areas can feel neglected and abandoned, he said.

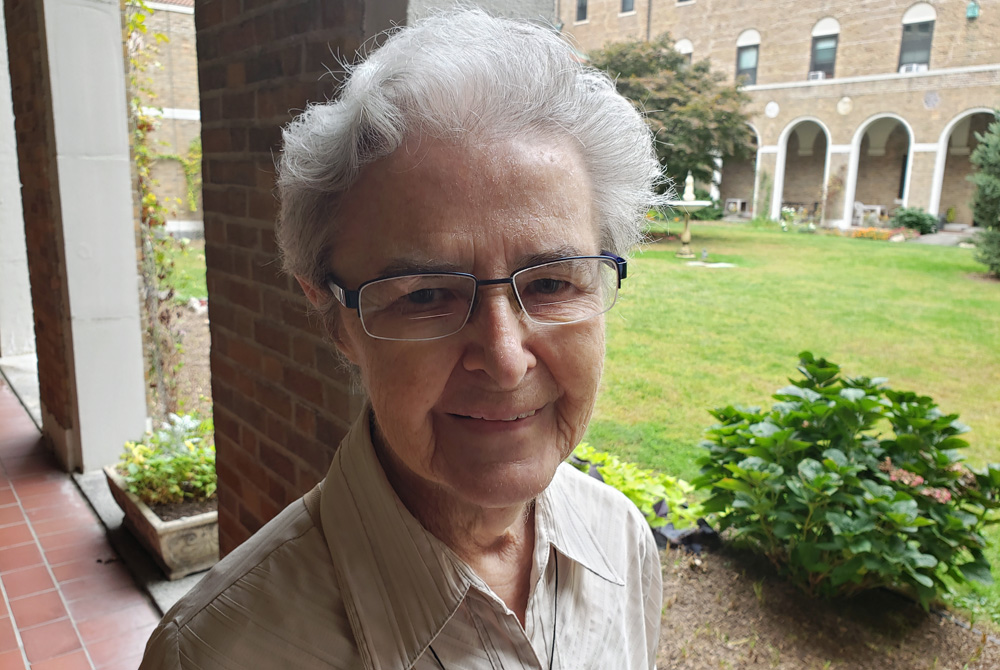

Maryknoll Sr. Angela Brennan understands those dynamics in El Salvador. Brennan returned to the U.S. in 2018 after eight years of prison ministry in El Salvador, including at maximum and other high security prisons. One of three Maryknoll sisters in El Salvador at the time, she worked as a member of an archdiocesan prison ministry team. (She is not affiliated with the Color Movement.)

Brennan cited bureaucratic challenges in the prison system for her return to the U.S. and has no immediate plans to return to El Salvador.

Calling herself "privileged" to minister to incarcerated gang members, Brennan believes that many gang members grew up in a war-fueled environment in which families were divided and separated. Many joining gangs said they "found acceptance and support" within them, Brennan said in a recent interview with GSR at the Maryknoll Center in Ossining, New York. "It's like a family."

Brennan noted a "post-war dilemma" in which "many teens and, later, children as young as nine years old, looked for 'family' (kinship) from older youth, gang members, with whom they were proud to be seen, like older brothers and sisters with whom they felt safe, at least at first."

While saying that "you can't generalize about all people," Brennan said many of the gang members she met simply didn't have anyone "who believed in them."

"You are not your crime," she recalled telling prisoners. But sadly, she said, "Society looks at them like they are [their crime]."

Maryknoll Sr. Angela Brennan returned to the United States in 2018 after eight years of prison ministry in El Salvador, including at maximum and other high security prisons. (Chris Herlinger)

And youths like Juan who die on the streets of El Salvador are remembered exactly for that.

It needn't be that way. Martinez notes that the young people in La Chacra who remain in the parish school are intent on not joining gangs, and that may have something to do with family pressure or the ability to see a future beyond the streets. "The kids in the school have an interest to know and to study. They want to know about things and learn," she said. "That's why they're not in gangs. They grow as human beings."

One youth grateful for the work of the sisters involved in the Color Movement is 16-year-old Jefferson Rafael Carabantes. He spends a few hours a week seeing friends and playing soccer at a center run by the Guardian Angel sisters in Apopa, another community on the outskirts of San Salvador also challenged by a gang presence.

"We feel so safe here. So safe. So great," Carabantes said. If Apopa's day-to-day environment doesn't feel safe, the center feels secure. "They treat us beautifully," he said of the Guardian Angel sisters. "I'm really, really grateful."

Asked about the gang situation, Carabantes said his parents — his father is a salesman, his mother is a vendor of baked goods — are careful about when he goes out on the street. "If you search for it, you'll find it — if you search for a gang, you'll find it," he said.

Has he been tempted to join a gang? "No. I want my mom to be proud," he said. "If you want to follow the good path, don't follow something that won't be good."

One youth grateful for the work of the sisters involved in the Color Movement is 16-year-old Jefferson Rafael Carabantes. He spends a few hours a week seeing friends and playing soccer at a center run by the Guardian Angel sisters in Apopa, another community not far from San Salvador also challenged by a gang presence. "They treat us beautifully," he said of the sisters. "I'm really, really grateful." (Chris Herlinger)

Martinez and her other sisters take a pastoral approach to gang members. Though the members mostly stay away from the school, the sisters have allowed some to use the facility's basketball courts for an hour each afternoon. Sometimes Martinez provides them with a little lunch — a kind of neutral act that doesn't threaten anyone.

"One reason why the gang members might respect the house (the parish school) is because when they get in trouble and go to court they need to do community service. And the sisters let them do it in the center," Martinez said, referring to the school and school rooms used for after-school activities and parish services. "They clean floors, take out the trash … they always pick the center for community service. They respect this place."

That amounts to a kind of "normal relationship," she said — though still not comfortable enough for her to ask the young people why they belong to a gang.

In the end, speculation doesn't count for much. Martinez can only be sure that in the case of Juan, a young man is dead, his family still grieves and gangs still control the streets of La Chacra.

Advertisement

Juan's mother told Martinez before her son died that, "I hope my son rests in peace." The mother knew that Juan's path would probably end violently. "She knew there was no way he was going to change."

The tragedy of Juan's death still haunts his family, Martinez said. The young man's sister, she said, "feels guilty, feels isolated." She doesn't leave the house and cuts herself. Martinez has reached out to the sister, urging her to come out of the house. But to no avail. "She feels such guilt, such isolation."

One hope is that Juan's younger brother, now 17, has not joined a gang, Martinez said. He is still in school, and has been involved with Color Movement activities.

"He was a part of the first core group of kids to give us ideas," said Alight staffer Carly Lunden, such as acquiring more books for the parish school library, organizing picnic lunches for families and getting more soccer equipment.

"He helped to brainstorm ways to make his community and his family stronger," she said, "and then helped to participate in bringing those ideas, and the Color Movement, to life."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is cherlinger@ncronline.org.]