Sr. Marjolein Bruinen, front left, on a visit with inmates of the women's prison (Frauengefaengnis) in Riga, Latvia, in 2008 (Bethany Dominicans)

Fifty years ago, I was engaged to be married when God found me in Aruba on vacation and lured me into religious life through the Sisters of Bethany. Although baptized and educated as a Catholic, I had no interest in church or religion, so it was a shock when I heard in my heart: "I want you with your whole life and all you have." What could I do but leave behind my fiancé and dreams of a married life?

I was drawn to the Dominican way of life, and the story of the Dominicans of Bethany amazed me. Its unique beginning was 155 years ago, in 1864, in a women's prison in Cadillac-sur-Garonne, France. A young priest, Dominican Fr. Marie Jean Joseph Lataste was assigned to preach a retreat for the women inmates at the local prison. He was not excited about it, since incarcerated persons were not those he wanted to associate with. But he went out of obedience, expecting nothing. To his surprise, 400 inmates came to the night retreat after working for the previous 14 hours.

In shock, he welcomed them as he thought Jesus would: "My dear sisters." Having been called "tramps" or worse for most of their lives, hearing someone address them as "dear sisters" brought most of them to tears. These women were not hardened criminals. They were women from poor country families who sent their daughters to the city to find work, which they most often found with wealthy families. However, once they were employed, abuse and frequent rape were common. When an unwanted pregnancy occurred, they were chased away penniless. Having no way to raise a child, in desperation the women often aborted the babies. When their action was reported (sometimes by the rapist himself), they were imprisoned as child murderers.

Advertisement

Fr. Lataste, of course, knew this history. When he saw the tears, he told the story of Mary Magdalene as he knew it at that time. Mary, known in the city as a prostitute, meets Jesus and repents because he shows her unconditional forgiveness and love. Father told the women that Jesus offers them the same forgiveness and unshakable affection of God. The words often touched the innermost longing of their hearts to give themselves to God.

After many encounters with the women and experiencing their conversions, Fr. Lataste said that even prison could become like a convent for them. This idea eventually evolved into founding a religious congregation for those released from prison. For some, release from prison meant facing more rejection and despair and sometimes led to suicide. Having an alternative gave them hope, even if they did not remain sisters.

Mother Henri-Dominique Berthier and Fr. Lataste together founded the congregation in 1866 in Frasne-le-Château; they were called the Dominican Sisters of Bethany with the motto: "The greatest saints have a past, and the greatest sinners have a future." The name was based on Lataste's interpretation of the story of Martha and Mary. Martha was characterized as the righteous woman, while Mary was the sinner who seemed to love Jesus more, sitting at his feet as she did. "Happy are those whose past urges them on to greater love," is another group motto.

A children's village in Horn Netherlands, pictured in about 1950 (Bethany Dominicans)

Experiencing the overwhelming forgiveness and love of God is the spiritual bond among the sisters of Bethany, whether or not they have been in prison. They practice a tradition of privacy about their former lives, only sharing it if they choose to do so. Some use their past life and conversion as examples for those to whom they minister.

The congregation increased its membership in France, and young women from Germany also entered. However when World War I occurred, 22 of these German women, including one professed sister, fled for safety to Venlo, Netherlands. Communication with the French foundation was difficult to maintain, so the bishop of Roermond, Netherlands, approved the group as a contemplative congregation in his diocese.

That changed after World War II, when many children were orphaned or abandoned by parents who had been imprisoned as collaborators. The bishop asked the sisters to care for these children. They lived in separate houses for boys and girls, which meant breaking up families. This practice persisted until a family of eight arrived and the eldest girl said outright: "Don't you even think we're breaking up; we've been through too much trouble together for that. We are either together or we leave."

So the children's homes transformed into Bethany Children's Villages, a precursor of SOS Villages of today. In these villages, children lived a semi-normal form of family life, with a sister or lay woman as the "mother." Throughout the various changes in our congregation from contemplative to active and combinations of these two elements, women from prison still entered, and ministry to women in and out of prison continued. Today, our congregation has a membership of about 100 located in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany (adjoining children's villages) and Latvia.

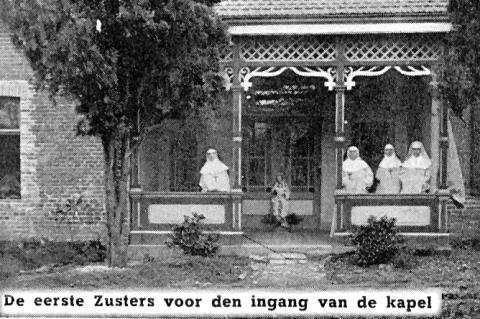

The first community of Bethany Dominicans are pictured in 1914 in Venlo, Netherlands. The caption imposed on the image reads: "[Photo] of the first sisters before the entrance of the chapel." (Bethany Dominicans)

Latvia is our newest foundation. In the early 1990s I was asked to found a community in a new country. Our first impulse was to go to Korea, as some Korean women had entered with us in Germany, but they had no desire to return. The master of the Dominican order then asked us to consider the Baltics — recently liberated from communism. Latvia was our choice, so four of us moved to Riga, the capital.

Our house had no heat and only limited water and electricity — winter was almost unbearable. Living in a society transitioning from communism to freedom was also challenging. The society looked down on Catholics, considering them "poor, filthy and smelly" people. Those who were not exiled to Siberia for religious beliefs were not allowed to study; they became unemployable and lived in abject poverty.

Two groups of Catholics emerged throughout the years of communism. One group remained faithful to their faith and practice: these were persecuted, tortured, deported or killed. The other group adapted themselves so they could live in peace, but they often helped each other maintain their faith in secret.

Catholics themselves were unfamiliar with active sisters, but gradually accepted us. Many young women entered and left. Today three Latvian and one German sister of our congregation remain in the Bethany community in Riga and are a vital part of the Latvian church. The sisters offer reflection days for youth and elders, teach Communion and confirmation classes, offer massage to the inmates of Riga's women's prison, give weekly radio instruction, visit those who need assistance, and provide refuge for women in danger. They also provide a safe living space for students in their convent, where they all live cordially with the sisters.

Bethany Dominican community pictured in Riga, Latvia, in 2003 (Bethany Dominicans)

Our charism was also transported to America: One woman who entered and left became the foundress of a Bethany community in a Norfolk, Massachusetts, prison for men. As a lay woman, she was assigned as chaplain to the prison by the bishop of Boston. Her message of God's mercy and love ignited a fire of devotion that led prisoners to form a community of prayer. In 1999, the Master of the Dominican Order, Timothy Radcliffe welcomed them into the Third Order of Dominicans. The prison administration provides them with a chapel where they celebrate liturgy of prayer and Eucharist. One of the brothers said: "… Bethany community is nothing more or less than a miracle… ."

Being part of these Bethany evolutions has been a fruit of God's call that I never dreamed of.

[Born in the Netherlands, Marjolein Bruinen taught and directed a school for secondary education there before entering her congregation in Aruba in 1975. Later, she ministered in Germany and Italy, helping direct the congregation's children's villages. Called to Riga, Latvia, she established a community of the congregation there. After the Latvian sisters were able to take over its leadership and a short sabbatical, she served in the Generalate, in the Netherlands, for 12 years. In those years she was also involved in actions against human trafficking. Currently she is the General Secretary of the Union of the European Conferences of Major Superiors (UCESM).]