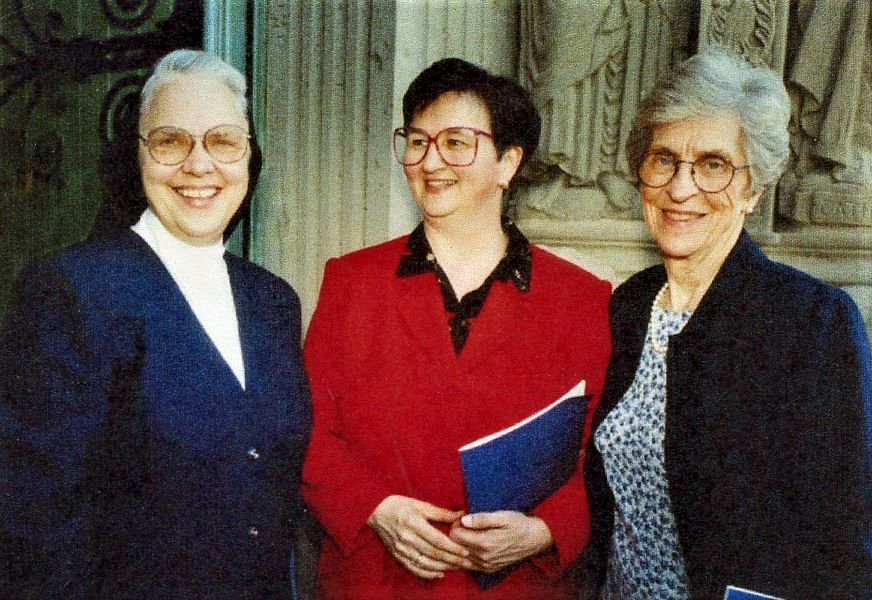

The inaugural recipients of LCWR's Lifetime Achievement Awards: from left, Sr. Amata Miller of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary; Sr. Helen Prejean, a Sister of St. Joseph; and Sr. Joyce Meyer of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Photo courtesy of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary; CNS photo/Paul Haring; GSR photo/Gail DeGeorge)

On Aug. 13, the Leadership Conference of Women Religious will hand out three Lifetime Achievement Awards, the first time the organization, which represents about 80% of the more than 40,000 sisters in the United States, has given the award.

The inaugural recipients are:

- Sr. Amata Miller, a member of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and an economist who has taught countless sisters and students about economics as a tool for social justice;

- Sr. Helen Prejean, a Sister of St. Joseph whose tireless advocacy against the death penalty was made famous in her book Dead Man Walking and the movie of the same name; and

- Sr. Joyce Meyer of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who is a member of the board of directors of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and Global Sisters Report's international liaison.

The recipients were scheduled to receive the awards last year, but the presentation was pushed back in hopes they could be given out in person this year. This year's assembly will also be virtual, but the three will be presented with their awards anyway.

Sr. Amata Miller: Educating others on economics, to effect change

For Sr. Amata Miller, economics isn't just about understanding how the world works, but also why it doesn't work for so many people. It's about addressing the hard questions of inequality, poverty and homelessness, about using investments and advocating for public policy to effect social change and create a more just and equitable system.

"If you want to change the world, you've got to understand it," said Miller, a member of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary who has taught economics at Marygrove College in Detroit; St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas; St. Catherine University in St. Paul, Minnesota; and at countless workshops across the country.

Miller initially studied economics because she was assigned to: The community's economics professor at Marygrove College was going retire, and the school needed a replacement.

Sr. Amata Miller of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (Courtesy of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary)

"People forget what religious life was like then," said Miller, 89, who recently celebrated her 70th jubilee.

She had been a math major and, at the time, hardly understood what an economist was.

"It took me four years of graduate school to say yes to God," she said. "A friend said, 'It'll be OK when you start teaching it.' And it was, and I enjoyed it."

Economics gave Miller a platform to expand on the social justice teachings she'd been steeped in since childhood. She was the eldest of four children, and her parents demonstrated to her, her two sisters and brother the importance of living out Catholic values: They opened their home to World War II refugees from Europe, and her mother gave talks on disarmament.

"That spirit of social justice was engrained in me," she said.

Jesuit priests and Immaculate Heart of Mary sisters at Gesu Catholic Church and Immaculata High School in Detroit reinforced those lessons. By second grade, she knew she wanted to be an Immaculate Heart of Mary sister and entered the community in the class of 1950 at age 17.

After stints teaching at Detroit-area grade schools, she attended graduate school at St. Louis University and the University of California, Berkeley.

Though she was one of only 10 women in the economics program at Berkeley, "I never thought of myself as a feminist and pioneer," she said. Being dressed in a full habit made her even more of an oddity on campus, she said.

In the wake of the Second Vatican Council, the issuance of Gaudium et Spes in 1965, and bishops' letters about economic justice and peace, women religious were encouraged to apply the council's teachings to their communities.

"It was important to know about economics if you're going to deal with the sorrows of the world," she said.

"It was important to know about economics if you're going to deal with the sorrows of the world."

—Sr. Amata Miller

Changes within religious congregations meant sisters had to learn about personal finance and budgeting because for the first time, individual sisters had control over some of their own money. Before Vatican II, communities had invested large sums of money into new hospitals, schools and other facilities. But as it became clear that sisters were going to have to provide for their own retirement, congregations realized they had to invest.

At the same time, the corporate social responsibility movement was growing, and faith groups, including Catholic sisters, were pressuring corporations to stop doing business in South Africa to help end apartheid. The Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility formed in 1971 to coordinate and enhance efforts to advocate for a number of environmental, labor and social issues, with Catholic sisters often taking a lead role.

In 1976, Miller became the financial vice president of her community while continuing to teach and give workshops. Exemplifying the congregation's social justice commitment through social responsible investing, she filed shareholder resolutions at meetings of Detroit Edison out of concern for the safety of the Monroe County Fermi 2 nuclear reactor site. She emphasized fundraising and congregational saving to provide for sisters' retirement and assisted other religious congregations in their efforts to increase compensation for women religious.

Miller traveled to congregations across the country in the 1970s and '80s, conducting workshops on personal finance, budgeting and investments.

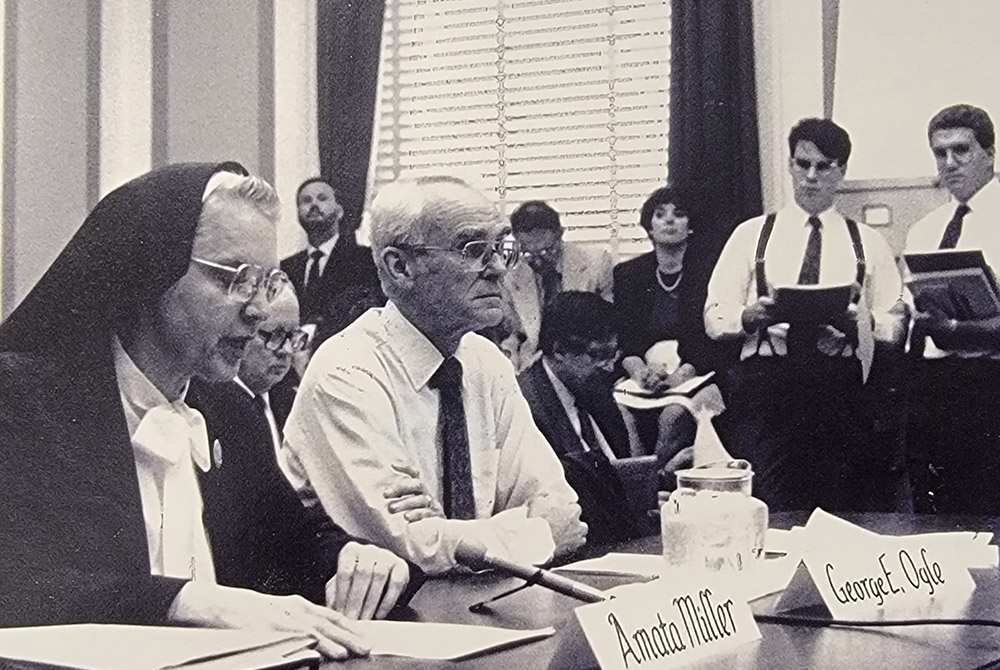

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Amata Miller, coordinator for Network, and George Ogle of the United Methodist Church testify June 27, 1990, before the U.S. House Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs regarding the Economic Adjustment, Diversification, Conversion and Stabilization Act of 1990. (Courtesy of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary)

"She could explain how to use your money in a way that people who didn't know about economics could understand it," said Sr. Corinne Florek, an Adrian Dominican sister and former executive director of the Religious Communities Impact Fund.

Unless a sister was in top management of a school or hospital, "the idea of how to use money, let alone how to use it for mission, was alien," Florek said. "Amata was a great educational resource to educate all of us."

In the 1980s, Miller became connected with the Catholic social justice lobby Network through Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Nancy Sylvester, who was then the national coordinator, and Adrian Dominican Sr. Carol Coston, the founding director. She worked at Network in Washington, D.C., from 1988 to 1994 as education coordinator and economic analyst, training sisters and laypeople in social activism and Catholic social teaching, writing position papers. She also testified before congressional committees about the detrimental effects of the military arms buildup, poverty issues, and the impact of legislation on economic policies.

"I knew Network would be perfect for her," Sylvester said. "She could say the most radical thing, and people of all persuasions could hear her."

From left: Sr. Amata Miller, Sr. Andrea Lee and Sr. Margaret Brennan in front of the Our Lady of Victory Chapel at St. Catherine University in St. Paul, Minnesota, in the early 2000s (Courtesy of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary)

Miller continued to wear a habit and then at least a veil until 2005, long after other sisters in her community had given them up.

"We needed to have bridge people," she said. "I could say things that sounded radical by looking like a conservative."

Miller continued to work as a financial director at colleges and teach economics, her passion. She retired as professor emerita from St. Catherine in 2016 and continued to teach at Marygrove College until it closed in 2019.

News of the LCWR award has prompted accolades from many former students.

"I'm getting all these tributes that we woke them up and made the world present for them, and it has influenced their own life choices," she said.

Advertisement

Sr. Helen Prejean in her home in Louisiana in 2019 (Courtesy of Ministry Against the Death Penalty/Cheryl Gerber)

Sr. Helen Prejean: Teaching others through her witness

Sr. Helen Prejean has spent more than six decades in ministry, with half of that devoted to a prominent campaign against the death penalty.

But the Sister of St. Joseph, 82, says it's too early for a lifetime achievement award because she's nowhere near done working.

"We are making progress, and we're going to keep doing our work," Prejean said. "It is going our way. [Capital punishment] is going to end."

Prejean said she is "just touched" by the award but insists the spotlight should be on the work of all sisters, not just her.

"I have such respect for my sisters that do the work steady, day in and day out," she said. "So you know what I'm going to do? I'm just going to be a prism reflecting the light right back on them."

Prejean said Catholic sisters are like the root system of a tree, constantly nourishing and anchoring the church in the Gospel.

Sr. Helen Prejean with death row inmate Dobie Gillis Williams at Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana in 1999. Williams was executed that same year. (Courtesy of Ministry Against the Death Penalty/Joup Bouma)

Prejean worked in Catholic education for decades but shot to national prominence when her 1993 book Dead Man Walking was made into a 1995 movie starring Susan Sarandon, who won an Academy Award for her portrayal of Prejean, and Sean Penn. The book, which sold hundreds of thousands of copies and has been translated into 10 languages, has also been made into a play and an opera.

Prejean spends her time working to end not only capital punishment, but also support for it among those who call themselves people of faith. When Dead Man Walking was published, national support for the death penalty was higher than 80%, according to Prejean's Ministry Against the Death Penalty. In 2021, support had fallen to 60%, with only 27% saying they "strongly favor" capital punishment, Pew Research Center reported.

Prejean personally implored both St. Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis to strengthen the Catholic Church's opposition to capital punishment. John Paul later declared it was only permissible in very few instances, and Francis said it was never justified and called it a "grave" violation of human rights.

"I just got lucky and met two popes," Prejean said. "I'm just trying to do my best with what I know."

Sr. Helen Prejean outside of Angola State Penitentiary in Louisiana in 1999 (Courtesy of Ministry Against the Death Penalty/Joup Bouma)

Prejean's 2019 book River of Fire: My Spiritual Journey is a memoir of the years leading up to Dead Man Walking and how she came to focus on social justice issues. The preface to the book begins with a poem she wrote:

They killed a man with fire one night,

strapped him in a wooden chair and pumped electricity

into his body until he was dead.

His killing was a legal act.

No religious leaders protested the killing that night

but I was there. I saw it with my own eyes

and what I saw set my soul on fire,

a fire that burns in me still.

When Global Sisters Report interviewed Prejean by phone for this story, she was in Montana, working on another memoir, Riding the Mighty River, on the experiences and encounters she has had with people as well as her meditations and insights.

Prejean has essentially been on a speaking tour since the 1990s, and while the coronavirus pandemic limited her travel — "I got to go home for 11 months, and I got to cook some good Louisiana food," she says — she didn't slow down.

St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean spoke with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in a panel discussion that included Prof. Vincent Harding at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, May 11, 2011. (Courtesy of Ministry Against the Death Penalty)

"I was busier than I was before COVID," Prejean said. "I did 150 engagements last year because Zoom makes it so easy."

She said virtual appearances allow one to, at least virtually, have the characteristics of the resurrected body of Christ, who could go through locked doors and appear in the midst of groups.

Between speaking engagements, Prejean counsels prisoners on death row and works with family members of murder victims. She is currently a spiritual adviser to one prisoner on Oklahoma's death row and another in Louisiana.

She also facilitates education programs on capital punishment for colleges and high schools.

"You've got to teach people. You've got to persuade them. And you do that through stories," Prejean said. "Those of us who are witnesses to this, we've got to get out and tell people what really happens."

Sr. Joyce Meyer: Serving as a citizen of the world

She grew up in a town so small, her primary school had only 12 students. But Sr. Joyce Meyer, a Presentation Sister of the Blessed Virgin Mary, has truly become a citizen of the world.

Now, Meyer's work on the board of directors of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and as a founder of Global Sisters Report, where she is international liaison, has her traveling nearly constantly: She has visited 57 different countries and counting. (The Hilton Foundation is a funder of Global Sisters Report.)

"I never expected that I'd be given an award for something I have such joy in doing," Meyer, 80, said in an interview with Global Sisters Report. "My years working with these sisters has been pure pleasure, a pure privilege."

Sr. Joyce Meyer of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary with sisters in Malawi (Courtesy of Joyce Meyer)

Born in Willmar, Minnesota, in 1941, Meyer is the eldest of six children. She did not attend Catholic schools but was contemplative and liked to read about saints. She thought religious life might give her experiences she would never have in Willmar.

"There was a spiritual adventure about religious life," she said. "I didn't want to be stuck in a small little town for the rest of my life, and I thought that religious life might give me opportunities, but never thought it would go where it did."

Eventually, she narrowed her choices of congregations to the Presentation Sisters and the Franciscans.

"I went home and flipped a coin — heads for the Franciscans; tails, the Presentations — and it came up Franciscan, but my gut said, 'No, join the Presentations,' " Meyer said.

She was initially a teacher, then earned a degree in theology and wrote about the spirituality of her congregation and its foundress, Nano Nagle. Always interested in international service, Meyer moved to Zambia in 1981 to teach English at a secretarial school and later served as secretary for the Zambia Association of Sisterhoods. Eager to develop local sisters, she made sure a Zambian sister replaced her when she left the country after five years, returning to South Dakota to serve in community leadership, including eight years as president.

Her horizons expanded in 1999, when she joined the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters, which provides grants for sisters' projects worldwide. The United Nations' millennium development goals, released in 2000, provided a framework to expand the fund's reach, and Meyer traveled to more than 50 countries to visit projects and encourage sisters to apply for grants.

Sr. Joyce Meyer of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary visits with tribal undocumented families in the mountains between Vietnam and Cambodia. (Courtesy of Joyce Meyer)

Meyer's engaging smile and delight in learning about other customs and cultures won her friends around the world. She has jumped over a cow as part of a ceremony in South Sudan and done the chicken dance with Karen refugees on the border of Thailand and Myanmar.

She joined the board of directors of the Hilton Foundation in 2009, and over the next several years worked with Thomas C. Fox, then the publisher of National Catholic Reporter, to create a publication that would report on the work of and be a platform for Catholic sisters, resulting in Global Sisters Report. As its liaison for international sisters, Meyer taps her widespread contacts to encourage sisters to write columns and connect journalists with sources for stories. Thanks to her work, more than 340 sisters, associates and oblates from more than 45 countries have written for GSR.

Meyer said her travels have shown her that the future of religious life is in developing nations.

"We need to find ways of partnering with sisters there so they can shape religious life into the future the way they want to or the Spirit leads them so we can support them however that may evolve," she said. "Working with the sisters has been my constant form of transformation. ... I've learned so much from them about courage and living simply without fear and facing all sorts of challenges."