Sr. Sheila Campbell reminisces on her world travels (Courtesy of Sheila Campbell)

Back when I was 18 and joined the Medical Missionaries of Mary, I could never have imagined the life that was to unfold before me. Part of the journey was traveling outside of my own culture, adapting and adapting again every time I moved. What helps adapt to a new culture? What hinders involvement with the new? I am not a psychologist, sociologist or any other "-ologist," but I do have my life experience and information from others.

At the age of 27, I left Ireland and England, where I was born and educated, and went to Brazil. As a more experienced sister said to me at the time, "I can understand what you are going through, but I can't help. I can't do it for you." Since then, I have watched several other sisters, priests and lay missionaries as they went through the transition process. Perhaps by sharing, we can alleviate some of the loneliness of that period.

Moving to a new culture does not automatically mean that you take on that culture; people can cling to their own traditions in "cultural ghettos." Think about young professionals who take on short-term contracts abroad for their firms or government. I met some of these in Brazil. Some came with their families but only mixed socially with their own and lived in comfortable middle-class areas, often symbolically (and tragically) surrounded by high walls and armed guards.

Unfortunately, even within the church and mission-sending groups, the same thing can happen. To mix socially with only one's own nationality, to shrug off difficulties and the hard work of transitioning with an "I'm only here for two to four years" promotes an attitude of service to the poor rather than learner with the poor.

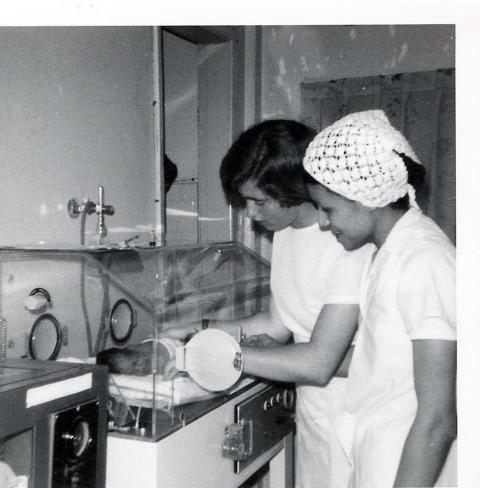

Sr. Sheila Campbell, left, and another nurse work with a baby at a small diocesan hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, in the late 1970s. (Courtesy of Sheila Campbell)

What helped me understand the process of transitioning between cultures was an article (later a book) by Sean D. Sammon, describing midlife transition as having:

- an ending;

- a seemingly unproductive "time out" during which the person feels disconnected from people and things in the past and emotionally unconnected to the present; and

- a new beginning.

For missionaries, the ending is often a little missioning ceremony and the goodbyes to friends and family. It can be a bittersweet time: You want the new experience but don't want it, all at the same time! And when you arrive, you still cling to the before.

In my day, it was letters and trips to the post office; nowadays, it is social media like Facebook. We surround ourselves with photographs and souvenirs, play music from home, sing our songs. For missionaries I have known, food becomes an important issue. Some foods evoke memories: We had many a "Passover meal" of Irish bacon, sausages and Irish brown bread in our small kitchen in São Paulo.

Facing a new language is another ending. No more am I understood by nor can I understand the people around me. My independence is stripped from me, as I cannot travel alone, talk with people alone or shop alone. I lose a sense of being in control of my own life and may react in anger. One sister who went to America when she was 18 shared with me her anger at not being understood when she spoke. There was only one right way of being a religious, and it involved the way you walked, talked, ate and even wrote. She was forced to change her handwriting to "the American way" and naturally felt violated in her personhood.

The experience of anger is very common. My brother shared his frustrations and anger at Japanese power outlets that didn't fit with his Western machinery. ("These damn sockets, why won't they work?") Allowing Japan to be Japan was crucial in his adapting. If I keep up negative comparisons, I withdraw and end up as an observer rather than a participant in the new experience.

Advertisement

These initial letting-gos are stressful, and it is normal to feel an increased need for privacy and independence. Enabling a person to accept and value these as legitimate needs at this time will not encourage the person to opt out, but rather give a needed breathing space for the completion of transitioning.

The second period (of disconnection) begins once we have enough psychic energy to let outside influences into our world. I remember my first sense of this: complaining to my friends, "It's not the language so much that is getting me down. I just don't understand the theology." I remember the first stirrings of excitement when I began to grasp some of the fundamentals of liberation theology.

But at the same time, I was upset because it didn't fit in with my own God-and-me, private spirituality I had worked at so hard to develop during my formative years. I began to love the rhythms and beats of Brazilian music, but was it good music? My brother in Japan sensed formality, a value in Japanese culture, and struggled to integrate this, given his own easy-going, extrovert charm.

The work of the second period is identifying the new values in the culture and constructively blending them into our own personal value systems. The actual experience of living through this period is one of the key factors in resolving it. As we live in the new culture, we gradually form friendships, live through historical events, and become immersed in life and work in new ways. More than anything else, it is the sharing of experiences that finally promotes the bonding necessary in the transition process. It is a period of confusion, of disconnectedness at times, but it is also a stimulating time for those open to the challenge of the new.

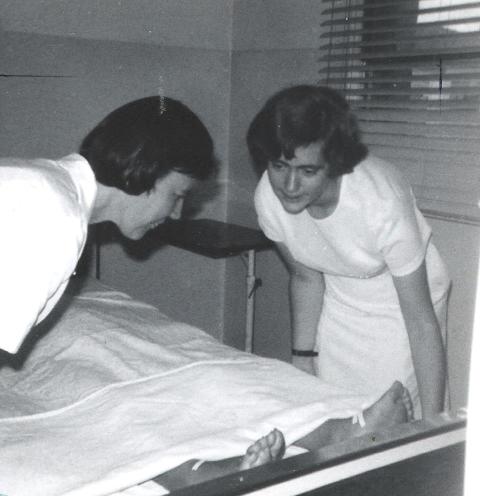

Sr. Sheila Campbell, right, and Sr. Edel Tanner make a patient's bed at a small diocesan hospital in São Paulo, Brazil, in the late 1970s. (Courtesy of Sheila Campbell)

Finally, there is light at the end of the tunnel! We come to the new beginning. In some ways, we never fully achieve transcultural transition, as we are always foreign or apart. And yet we achieve a sense of belonging. We begin to look at life through the eyes of the other culture. For some, this sense of comfort comes on slowly, and they are not aware of a new beginning. For others, a certain date or place will evoke the memory of arriving, of belonging. Some never get this sense and struggle with the new culture for many years.

One sister who had been in Pakistan for 15 years told me it took 10 years for her to feel this sense of ease. Why so long? She had been teaching in a school, and only when she moved out to live among the villagers did the transition process run its course. Perhaps institutions such as schools, hospitals or orphanages have their own subcultures that, in fact, block or lessen the transitioning experience?

I don't think I began my ending until I returned to Ireland for a five-month period and then returned to Brazil. I had forgotten so much of my Portuguese that I cried for the first month. But, in my tears, I recognized a feeling of wanting to be near the culture. In spite of my foreignness and incapacity, there was as a sense of homecoming. I spent 40 years in Brazil and became a Brazilian citizen. But that is story for another day ...

"Our first task in approaching another people, another culture, another religion, is to take off our shoes, for the place we are approaching is holy. Else we may find ourselves treading on [people's] dreams. More seriously still, we may forget that God was here before our arrival."

— Max Warren