Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Mary Alice McCabe welcomes an Angolan father and son to the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, in January 2020. (Courtesy of Mary Alice McCabe)

Successfully crossing the United States' southern border is only the beginning for the thousands of migrants who don't plan on building a home on the finish line.

Health care, legal assistance, interpretation, housing and financial aid, work — though the needs are many, migrants throughout the United States can look to women religious whose ministries focus on directing them to services they may not know how to find for themselves.

A quick rundown of Sr. Mary Alice McCabe's many regular tasks provides some insight to the challenges that come with such a dramatic resettling, as the Sister of Notre Dame de Namur does what she can to help the immigrants who entered the country illegally and refugees in her city of Baltimore.

Lately, McCabe has been interpreting for migrants out of her car by phone, connecting them with social, legal or health services. Sometimes it's to help them receive financial supplements and rent aid or sort out their documents; other times, it's interpreting for their lawyers or at health clinics.

Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Mary Alice McCabe, right, welcomes a recently arrived Honduran mother to a migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico, in 2019. (Courtesy of Mary Alice McCabe)

She also helps women with high-risk pregnancies who have recently arrived in the United States, accompanying them before and during the birth and, sometimes, through "really tragic situations" in which the babies have died.

When she learned of an immigrant family about to come to Baltimore, she used her personal contacts to set them up with housing. McCabe also recalled working with a Honduran woman who had broken her knee while traveling through Mexico, offering her assistance and getting her in touch with hospitals.

"If you shop around and keep going, you find out that it is possible to get free health care for immigrants in emergency situations," she said.

Then there's the social accompaniment, which includes attending birthday parties and gatherings at immigrants' homes to maintain a relationship and a sense of community.

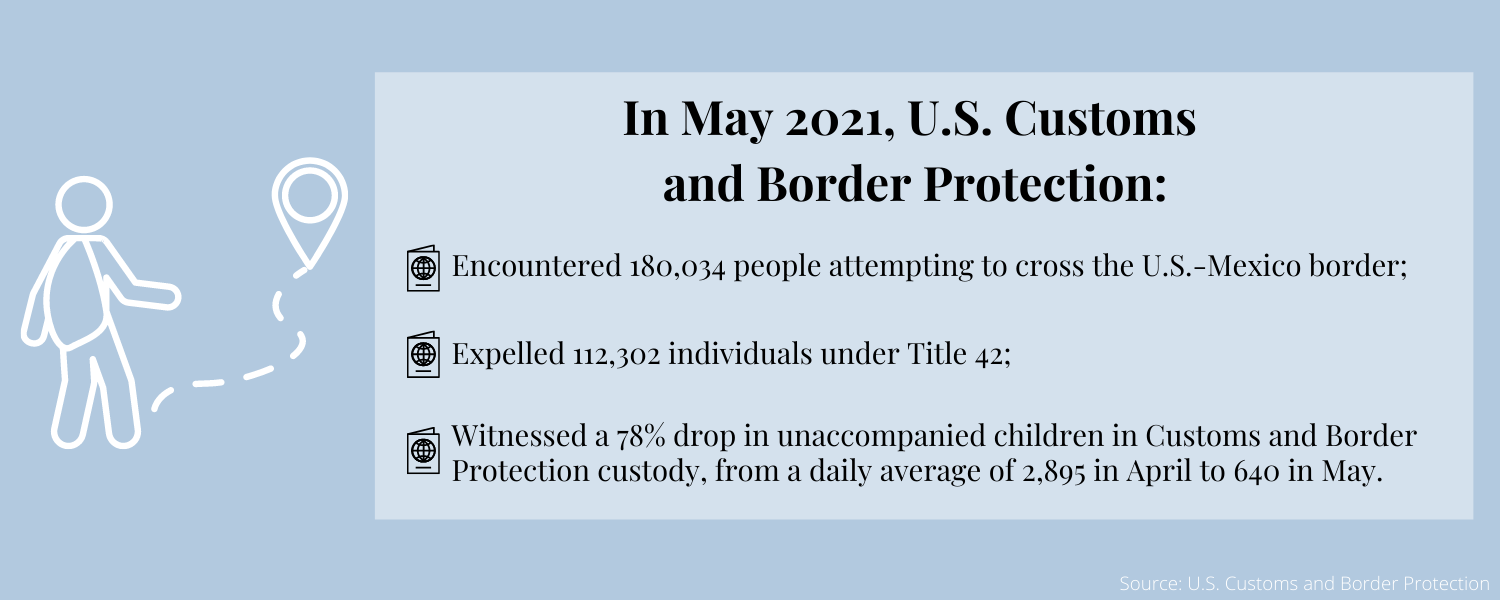

(GSR graphic/Soli Salgado)

Typically, sisters find themselves ministering to immigrants who have already established a life in their new town or city rather than those newly arrived to the United States after processing at the border.

Sisters who spoke with Global Sisters Report say that perhaps newly arrived immigrants don't connect with sisters quickly because they're still in survival mode. The basics are their focus: toiletries, cellphone chargers, shelter, food.

"They are at various degrees of suspicion with us," said Mercy Sr. Anne Connolly, speaking from her experience in McAllen, Texas. Exchanging just a few words with them, however, can ease their "angst."

Their lingering trauma, too, makes it difficult for them to open up. But once they do, sisters are there to help.

Notre Dame de Namur Srs. Mary Alice McCabe, center, and Jeanette Braun, right, use a tent as a makeshift office from which they helped the families at a migrant camp in Matamoros, Mexico, fill out their asylum applications in 2019. (Courtesy of Mary Alice McCabe)

As a counselor at Holy Cross Ministries in Salt Lake City, Sr. Verónica Fajardo of the Sisters of the Holy Cross hears her fair share of heartbreaking stories from migrants who have been referred to her for their mental health needs. Some of the migrants are victims of labor trafficking, sexual assault, abuse or being held captive; others have witnessed the death of family members or describe vividly a grueling journey to the United States from South or Central America.

Often, she witnesses post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and/or anxiety and gets immigrants in touch with crisis clinics if they are suicidal. The increase in numbers of newly arrived immigrants in the city has led to a waiting list for Holy Cross Ministries' counseling services, though the ministry also offers case management and health services.

Advertisement

"I can empathize with their experience of trying to leave war or violence because it's my own story," said Fajardo, who is originally from Nicaragua. "So, having come to the United States as an immigrant in a totally different time period but with similar circumstances, there's an understanding of that kind of difficulty of resettling in a new place, having a lot of questions, having difficulties in the new place."

Her clients who are new to the United States, she said, often wind up living in neighborhoods with high levels of crime, leaving them vulnerable to robberies and physical assaults.

"It's difficult, so I feel that it's great that we can provide the services and accompany people as much as we can ... supporting them and helping them deal with their symptoms," she said.

Holy Cross Sr. Verónica Fajardo, far right, leads a support group in 2019 in Salt Lake City in collaboration with Holy Cross Ministries and Peace House, a local domestic violence shelter. Now, Fajardo runs support groups via Zoom. (Courtesy of Verónica Fajardo)

Ministry to 'our sisters and brothers'

Located in 49 states with more than 380 organizations, the Catholic Legal Immigration Network Inc. (CLINIC) is the country's largest charitable legal immigration network, training nonprofit immigration lawyers to provide affordable representation.

Mercy Sr. Rosemary Sabino, who has worked with CLINIC in Miami for 20 years (Courtesy of Rosemary Sabino)

In Miami, Mercy Sr. Rosemary Sabino, an emeritus member of the CLINIC board of directors, said the increase in demand has led the local CLINIC office to be appointment-only rather than accepting walk-ins as usual. But with their help, immigrants receive the legal assistance necessary to help them stay in the United States or facilitate any other documentation they need. One of their tasks included attempting to reunite mothers with their children after they were separated at the border.

"It hasn't been very successful," she said. "We've reunited some, but we have a long way to go, and it's only going to get done through legal work."

Now, Sabino said, CLINIC is also helping immigrants who have been picked up for criminal offenses, most of whom have mental illnesses and/or are experiencing homelessness, particularly by helping them with paperwork to access the mental health services or housing for which they qualify. (Thanks to a grant from Sabino's Mercy sisters, which a corporation matched in donations, Miami's CLINIC now has $30,000 for this effort.)

Typically, these immigrants are made homeless as a result of not having work permits, she said — exactly the kind of thing that CLINIC can help with.

"It's not as difficult as you would think because we need workers," said Sabino, who has been with CLINIC for 20 years. "That's a true statement all over the United States, but I don't think a lot of states are willing to admit that. Here in Florida, we admit we need workers."

Outside Chicago, Mercy Sr. JoAnn Persch leads longtime ministries on behalf of migrants, advocating for those in jails and detention in her city and organizing efforts such as public protests and mass prayers while sending money to those locked up.

Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Mary Alice McCabe and a member of Witness and the Border protest the Migrant Protection Protocols on the Brownsville, Texas, side of the bridge to Matamoros, Mexico, in 2019. (Courtesy of Mary Alice McCabe)

Lately, her advocacy has included a project called Harper Hospitality, in which Persch and her fellow organizers work with churches and religious communities to sponsor housing for those newly released from detention, helping them establish a community while also offering a case manager if they have pending legal needs.

Persch's and her volunteers' presence is made known almost immediately to those arriving in Chicago by bus. When they learn migrants are about to arrive, a team arrives at the bus station as early as 4 a.m. with backpacks and basic necessities for the newly arrived migrants, who often have nothing but plastic bags on hand with their few items.

Throughout the pandemic lockdown, Persch said their programs never ceased running.

Following a 2018 vigil in front of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement headquarters in San Francisco, Mercy Sr. Judy Carle, left, and Mercy Sr. Joan Marie O'Donnell rejoice with Alexi, a migrant who had been freed from over a year in detention. The sisters became close with his family. (Courtesy of Judy Carle)

"We are committed to our immigrants, our sisters and brothers," she said.

Like Persch, Mercy Sr. Judy Carle and her community in Burlingame, California, respond to migrants' needs however they can, teaming up with local groups to form an interfaith solidarity committee. One of their more regular focuses has been accompanying migrants to their immigration hearings.

Now, their advocacy includes what they call a "freedom campaign." Carle said the group connects with immigrants who did time in jail for crimes they committed as teenagers but who, upon release, are then put into detention by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

"We've been involved with many of these cases; we know who they are, we know their families, and we've gone to their hearings on a regular basis," she said, adding that some cases do end in deportation.

Finding sponsors for housing is also on the group's radar. They use their interfaith network to find congregations or parishes willing to take in new immigrants.

McCabe said ministering to new immigrants also entails reaching the larger population to educate them on the importance of these new arrivals to the nation.

"They're good people. They're family-oriented, they're workers, and they just want a chance. They're respectful of the country and are so grateful for anything," she said.

"Those who know the immigrants up close and see their faces and hear their stories, they have no problem whatsoever in saying, 'Welcome.' It's those who don't know, who don't get close to them, who have a different attitude."