Sr. Imelda Wickham, a member of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, recently wrote a book about her experience as a prison chaplain. (Courtesy of Paula Nolan/Messenger Publications)

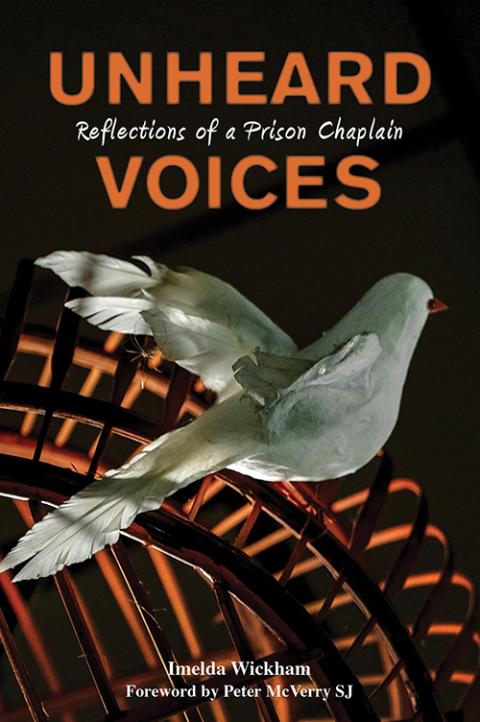

A new book, Unheard Voices: Reflections of a Prison Chaplain, spotlights Ireland's dysfunctional criminal justice system, which instead of rehabilitating prisoners with addiction and mental health problems often locks them up for extended periods of time in cramped prison cells.

The book's author, Presentation Sr. Imelda Wickham, was a prison chaplain for 20 years and held the role of national coordinator of prison chaplains for the Irish Prison Service for three years. She is a founding member of the Transitional Residential Accommodation for Independent Living, or TRAIL, which was set up in 2004 to provide high-quality transitional accommodation to offenders released from prison who would otherwise be homeless. (It is now part of the Peter McVerry Trust.) Currently, she is setting up a new project called New Directions, which will support the families of people in prison.

Cover of 'Unheard Voices: Reflections of a Prison Chaplain' (Courtesy of Messenger Publications)

Unheard Voices gives an insight into the reality of life within a prison. In it, Wickham expresses the hope that the criminal justice system can be transformed from being adversarial and punitive to restorative and healing, and argues that true justice lies in healing for all affected by crime, including victims, perpetrators and society.

"If we are talking about a more just, caring or safer society, how we deal with the perpetrators of crime is very key," she told Global Sisters Report.

GSR: You entered religious life at 18. Do you think it was too young?

Wickham: I was born and reared in a small village called Bree outside Enniscorthy, County Wexford. My father was a farmer, and I was the second-youngest of six girls.

I attended the Presentation Convent school in Enniscorthy. When I finished school, I entered the Presentation Convent. People often ask me why I entered. As a child, I had already decided that I would devote myself to God.

Looking back, I would say that I had a very personal relationship with the Lord during those formative years. It was a very deep calling; I believed in it, I followed it, and I have no regrets. But I didn't find it easy because at 18, your whole life is ahead of you. You see all sorts of possibilities and things you want to do. All my friends were heading off to college, careers and meeting boyfriends. I would have loved to have been part of that. I remember feeling, "Do I have to do this? Why am I different from everybody else?" But that was my calling.

Eighteen-year-old Imelda Wickham on Sept. 24, 1957, the day she entered the

Presentation Convent, in Wexford, Ireland (Courtesy of the Wickham family)

I trained as a primary school teacher in in Carysfort Training College in Blackrock, County Dublin, between 1959 and 1962 and taught in Enniscorthy for about three years before I did a bachelor's degree and a higher diploma in education and moved into second-level teaching in Dungarvan, County Waterford. I loved teaching. I loved seeing kids develop, find their feet and gain confidence in themselves. It's a wonderful profession.

There were so many fine young teachers, it dawned on me that as a religious, I was not needed in teaching anymore. I was called to move to the margins. At that time and still today, I believe the most marginalized are those in prison. It was a call within a call to be with people in prison. "I was in prison, and you visited me" from Matthew's Gospel resonated with me.

Having decided to change your focus and get involved in prison ministry, what was the next step?

I petitioned the congregational leader to free me up to work with the prisoners. I got permission, but then I was asked to become assistant provincial, and I responded to that. And then I was asked to become provincial, and I responded to that. So the prison work was put back. But I never lost the dream or the vision.

It was over a decade before I got a chance to go to Chicago in 1998 to do training in prison chaplaincy. I studied counseling skills and learned about drug addiction at Loyola University in Chicago, where the social teachings of the church came alive.

I then headed for the Vanier Centre for Women, a detention center in Toronto. I spent three months there in the women's prison and completed a semester in clinical pastoral education. I began to explore the possibility of remaining in the United States as a prison chaplain. I was prepared to uproot and move bag and baggage. But then I was given a five-year contract by the Archdiocese of Dublin that never ended. It was chaplaincy without parole for me!

While attending a Congregational Gathering in Zimbabwe in 1996, Sister Imelda met local artists to learn about the local culture. (Courtesy of the Presentation Sisters of the Blessed Virgin Mary)

Many would feel that as a female chaplain in a male prison, you were vulnerable, but you have written in your book that you met amazing people whom society had locked away. Though you also met some people suffering from mental illness, personality disorders, homelessness, addiction ...

I never felt intimidated. I felt very welcome from the day I went in. I became part of that prison community. We looked after each other in many ways. You become part of their lives.

When somebody comes into prison, one of the first people they will look for is the chaplain. That's part of your role. I was never too concerned as to why they were there. You just met him as he was. Very often, he would ask me to contact his family. So you began a relationship also with the family.

Advertisement

What changes would you like to see in the prison system?

My experience is that the criminal justice system is in dire need of radical reform. We need to stop and ask: Who are we imprisoning, and why are we imprisoning them? I believe the system is contributing to the high rate of recidivism, and we also must tackle the attitude that we lock people up and throw away the key. We hold people in custody at great financial cost to the state while claiming to rehabilitate them for their return to society. But whatever skills they had prior to imprisonment are lost and diminished while they are incarcerated.

In the years since I became a prison chaplain, new insights have emerged. The time for believing that society is safe when the perpetrators of crime are locked up in prison is long past. I have constantly said people who are mentally ill should be hospitalized. But society takes the easy way out and locks them up without adequately seeing what their needs are. I've constantly fought for treatment centers for those who suffer from addictions.

I think the only way we're going to bring about reform is by starting a national conversation about crime, punishment, imprisonment and responsibility that involves those affected by crime as well as the professionals, researchers, politicians and policymakers. Prison needs to be seen as a place where people experiencing certain difficulties in life are helped and retrained for future involvement in society.

Sister Imelda stands outside a prison in Ireland in 2005, waiting to meet some of the families of those in prison. (Courtesy of Sr. Imelda Wickham)

What alternative is there?

One model I look at in the book is restorative justice. I think it is very healing and totally underused in Ireland. It is used in many countries across the world and has proved very successful.

We need to consider new and creative ways of looking at human behavior. If you look back at how we treated children in the past and how we punished them — the world has changed. I think psychologists will show us the way.

Prisons could facilitate small industries where people could earn a living, pay for their keep and support a family. This would make not just good financial and economic sense, but also good social and moral sense. It would also give a sense of purpose in life to the incarcerated as opposed to the long years of idleness and purposeless living that many experience in our penal institutions.

You have now retired from your role as a prison chaplain, but you haven't left prison ministry.

I am now devoting my time to working with the families of people in prison through New Directions. Families are a key group. They are very often the forgotten ones, and their pain and suffering can go unrecognized. I have always felt that the families of the perpetrators are very often the secondary or tertiary victims of crime.

New Directions helps families deal with the fact that a family member has been sent to prison. They also support families as they prepare for the return of somebody who has been in prison. Often, they don't know how they will cope as a family. We provide one-to-one counseling or therapy for people who need it or a listening ear or emotional support. During the pandemic, we did this via phone, Zoom and video, and that brought us into contact with a wider range of people, including families in the U.S. and U.K.