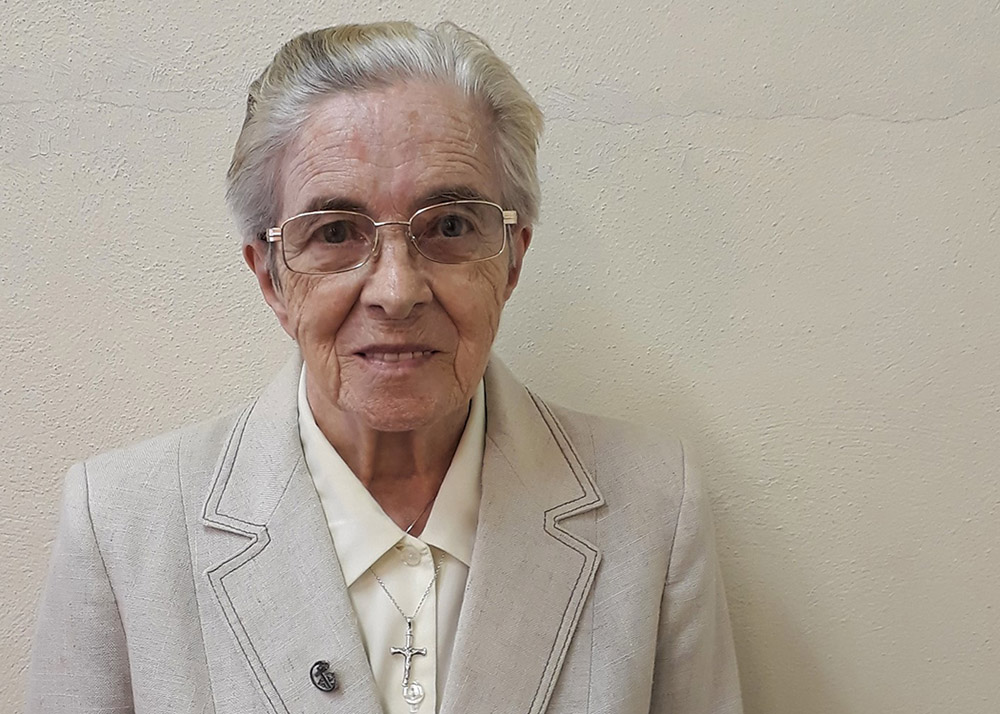

"I never thought of any other congregation but the Columbans," Sr. Mary Greaney, 87, says of her more than three decades as a missionary in Hong Kong and her more recent outreach to the Chinese diaspora in Ireland. (Courtesy of Sr. Mary Greaney)

Irish missionaries have a long history of "leaving our footprints in many countries worldwide," 87-year-old Sr. Mary Greaney tells Global Sisters Report.

Originally from County Galway in the West of Ireland, she joined the Missionary Sisters of St. Columban in October 1962, when she was 29. After profession in Ireland, she was sent to the nurse training school at Whipps Cross Hospital in London in 1966. A specialization in tuberculosis nursing at Royal Brompton Hospital followed in preparation for her assignment to Ruttonjee Sanitorium (now Ruttonjee Public Hospital) in Hong Kong. TB was a serious challenge in the British territory at the time.

Greaney arrived in Hong Kong in 1971 and spent the next 37 years as a missionary in the territory, nursing at Ruttonjee Sanitorium for 17 years before she became involved in establishing the Society for the Promotion of Hospice Care, whose motto is: "When days cannot be added to life, add life to days." She was also active in the Legion of Mary and prison ministry.

After retiring to Ireland in 2008, Greaney was instrumental in establishing a flourishing parish community for the Chinese diaspora in Dublin, acting as liaison between the Dublin Archdiocese and the Chinese community, working with a small team of Chinese and Irish volunteers as well as some Chinese priests studying in St. Patrick's College in Maynooth.

Members of the Chinese community at the 2018 Rite of Election in St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral in Dublin with Fr. Damian McNeice, right, of the Dublin Archdiocese's Liturgical Resource Centre (Courtesy of John McElroy)

Greaney once asked a member of the parish community why she was interested in becoming a Catholic, to which the woman responded, "Sister, we are free here to follow Jesus."

GSR: How did you discover you had a vocation?

Greaney: I was a late vocation. I'm from a rural parish: Caherlistrane near Tuam in County Galway. I was the eldest of the family; I had two brothers and two sisters. One of my brothers is a Servite priest in Chicago.

The Legion of Mary started in our parish in 1958, and I was one of the first to join it. Times were different then. Nearly everyone was Catholic, so we would go around visiting houses and doing evangelization.

My vocation really came from the work we did with Traveller children. They were living in canvas tents on the side of the road. They were really poor. Every week, two of us used to visit them and help prepare them for first holy Communion. It was while I was doing this that I began to think about being a missionary. It struck a chord.

What led you to join the Columban Sisters?

Dalgan Park, the first home of the Columban Fathers, was located down the road from my own home, so my family and the people in the locality were very familiar with the Columbans. My family subscribed to the Columban Sisters' magazine, the Star of the East, and so I read about the sisters.

Also, Sr. Mary David Mannion, who was a distant relative, had grown up in the area. She became a doctor and then joined the Columban Sisters. She worked in Korea. I really wanted to go out and help her.

Advertisement

I never thought of any other congregation but the Columbans. But I struggled with the idea. I was living at home and attending dances, and I had boyfriends. In my heart, I wanted to be a missionary, but I also didn't want to leave everything. Eventually, I wrote to Magheramore [headquarters of the Columban Sisters in County Wicklow], and they arranged an interview. When I entered, I was 29. Most joined at 18 straight from school, so there was a big gap with the others.

You were interested in being a missionary in Korea but ended up in Hong Kong, nursing those afflicted with TB.

After I made my first profession, I was asked what I wanted to do professionally. I had always wanted to do nursing, so I was sent to London to train. I still had in mind the idea of being a nurse in Korea. When I finished my nursing three years later, I was asked to do a year's postgrad in TB training at Brompton Hospital, and I knew it was for assignment to Hong Kong, where TB was rampant.

After I completed the course, I was assigned to the sanitorium where the Columban Sisters worked in Hong Kong. I had no regrets. I knew I was in the right place.

I arrived in Hong Kong in July 1971 at the hottest time of the year. We had no air conditioning and no fans, but plenty of mosquitoes! There were about 24 Columban Sisters in the community, and, at that time, we were involved in health care and hospitals. Later, we got involved in schools.

Ruttonjee was big a sanitorium with 350 beds. The Columbans didn't own it, but we administered it. There was a Columban sister on each ward and a Columban worked as the medical superintendent, as the matron and several doctors were Columbans.

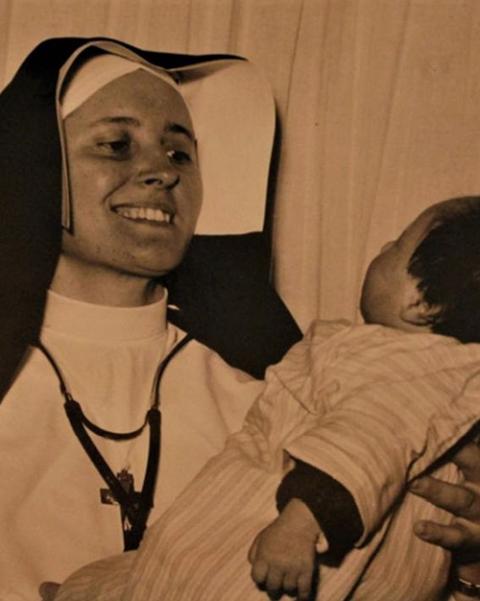

In 1978, Columban Sr. Mary Greaney, left, speaks to Columban Sr. Mary Aquinas Monaghan, who was the medical director at Ruttonjee Sanatorium for almost 40 years. The Columban Sisters were responsible for the administration of the sanatorium, including a nursing school, where they trained Chinese nursing staff. (Courtesy of the Missionary Sisters of St. Columban)

They were short of staff, and I was sent to a children's ward. I hadn't a word of Cantonese, which was so frustrating. You couldn't talk directly to the children. I had to get a nurse to interpret.

One day, a little girl with spinal TB said something to the nurse, and I asked what she had said. She had asked how I could be so stupid that I couldn't talk to her. I knew I needed to learn the language. I took six months off and did a crash course in Cantonese. Being able to speak to the patients directly completely changed my work in the sanitorium.

Why was TB such a problem in Hong Kong?

TB was rampant, particularly among those coming from China. It spread partly due to cultural factors. For example, the grannies often took care of the grandchildren. They would chew the food first and then put it in the child's mouth, which contributed to the spread of the disease.

We had a lot of refugees coming out of China. They even used to swim out across the South China Sea to reach Hong Kong. It was so dangerous. I had a patient once on my ward with TB who swam out to get treatment. He had been caught and brought back on two previous attempts. China wasn't open at that time, so having made it to Hong Kong on his third attempt, he could never go back. He was only 34. We kept patients like that for the duration of their treatment. He was with us for six months, and then he transferred to the convalescent home attached to the sanitorium.

I spent 17 years in the Ruttonjee Sanitorium, and by that stage, TB had become much less of a problem, partly because we had done so much. Our evaluation was that it was time to let go of the sanitorium, and so they built a modern hospital there, which is now a general hospital.

Columban Sr. Mary Aquinas Monaghan (1919-85), the first medical superintendent of Ruttonjee Sanatorium in Hong Kong and one of the first nuns to qualify as a physician in Ireland, in the 1950s. She collaborated with international research institutes to make significant contribution to tuberculosis management and received several awards for her work. TB was almost eradicated in Hong Kong by the time of her death, partly thanks to her immunization plan. (Courtesy of the Missionary Sisters of St. Columban)

Was ridding Hong Kong of TB one of the greatest legacies of the Columban Sisters?

It was. We had two doctors, Sr. Mary Aquinas Monaghan and Sr. Mary Gabriel O'Mahoney, who were internationally renowned for their work on TB. They were linked with Brompton Hospital and the Medical Research Council in London. They did a lot of research and wrote a lot about the treatment of TB, and we did lots of trials of TB drugs to see how effective they were.

Once we decided to let go of the sanitorium, we were looking for new needs. As missionaries, we always look around; we don't like to sit too long in one place.

Sr. Mary Gabriel O'Mahoney, who was the medical superintendent of Ruttonjee Sanatorium, and I were looking to see what was the greatest need we could meet in health care. There was no hospice care in Hong Kong, so we got a group together and did some research on the possibility of starting hospice and palliative care.

They were so eager to have end-of-life care because there was so much cancer, and among the Chinese, death is a taboo. They just don't talk about it. But that changed as we did a lot of education work through the hospice.

We also did home care with families. Sometimes, that space was tiny. I would be visiting a patient, and the family had just one room. But we worked on symptom control, and we also tended to patients' psychological and spiritual pain. Very few of them had any faith.

Were you able to do any evangelization in Hong Kong?

We were not allowed to evangelize on the wards of Ruttonjee Sanatorium. We did our evangelization through the witness of our care. But I maintained contact with the Legion of Mary in Hong Kong, making the link just two weeks after I arrived in 1971.

Why did you decide to return to Ireland in 2008?

I didn't want to leave Hong Kong, but I was over 70, and I thought if I am to get into anything in Ireland, it is time to move. There was something telling me I should go. I struggled with it for a whole year and discerned and prayed, and at the end, I knew it was time to move on. I came back and I took a break for a year, and then I got involved with the Legion of Mary.

Members of the Chinese diaspora in Dublin with Columban Sr. Mary Greaney, center, and Fr. Anthony Hau, the chaplain to the Chinese community from China, in 2017 (Courtesy of Sr. Mary Greaney)

You got involved in an outreach to the Chinese community in Dublin.

Most of the Chinese community were students. Some were casual workers, and some were illegal immigrants. My first call to mission was an invitation to visit and befriend Chinese illegal immigrants in Dublin's Mountjoy Prison.

At the time, there were several young priests from China studying in the national seminary in Maynooth. These priests used to celebrate a Mandarin Mass twice a month.

Soon, the community began to grow. I became the liaison between the Archdiocese of Dublin and the Chinese community. We set up a small team of Chinese and Irish volunteers under Fr. Anthony Xiao, keeping evangelization as the main focus of our mission. Sr. Lucia So, a Chinese Columban Sister from Hong Kong, was assigned to Dublin to help this young community.

A catechumen class was organized with an amazing response. We had an average of 20 young Chinese adults baptized annually at the Easter Vigil Mass in Dublin's Pro-Cathedral. It never ceased to amaze me how many young Chinese adults were eager to join the class.

I had some marvelous experiences in Hong Kong, and I loved my mission work there, but I will be eternally grateful to God for this special mission to the Chinese here in Ireland. It is a good example of reverse mission, especially for us Columbans, who were founded originally to work in China. It seems like my Columban missionary call has come full circle.