Sr. Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, a Catholic social justice lobby, speaks at a rally questioning the 2017 tax cut law at Lutheran Metropolitan Ministries headquarters Oct. 20, 2018, in Cleveland. She will step down from Network in March after having headed the organization since 2004. (CNS/Dennis Sadowski)

Editor's note: On July 7, Sr. Simone Campbell, a Sister of Social Service, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Joe Biden. Read more about the ceremony.

In honor of the award, Global Sisters Report is republishing this profile of Campbell's life and work that was originally published March 25, 2021, when Campbell was preparing to leave her role as the executive director of the Catholic social justice lobby Network. She is the second Network director to receive presidential honors after Dominican Sr. Carol Coston received the Presidential Citizens Medal from President Bill Clinton in January 2001.

For 40 years, the little Catholic social justice lobby Network had toiled in relative obscurity on Capitol Hill. As the group celebrated its anniversary in 2012, Sr. Simone Campbell, the group's executive director since 2004, and her colleagues wondered how to get their name out.

Four days later, the Vatican announced it was censuring the Leadership Conference of Women Religious for a host of alleged sins. Among them was working too closely with Network, which in Rome's view focused too much on social justice and not enough on abortion and gay marriage.

There was no longer any question of how to tell the world about Network.

"We often joked that we should send the Vatican a thank-you note," said Campbell, a Sister of Social Service.

The censure led to national media attention, and Campbell gave interviews on television shows, spoke at the 2012 Democratic National Convention and said a prayer at the 2020 convention.

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, addresses the second session of the Democratic National Convention on Sept. 5, 2012, in Charlotte, North Carolina. (CNS/Reuters/Jason Reed)

And, of course, it led to Nuns on the Bus, which raised Network's — and Campbell's — profile even further.

"It was a gift of the Spirit," Campbell told Global Sisters Report. "It really catapulted us to a new level."

At the end of March, Campbell will step down from Network's helm to go on an extended sabbatical to see where the Spirit will send her next. As for the first 75 years of her life, Campbell has no regrets.

"The Vatican named [Network] as being a bad influence, but that's how we got the bus," Campbell said. "It's a web. It's all woven together. I feel blessed beyond belief."

That gift Campbell has, of taking a devastating situation and turning it into a blessing, is one she has used all of her adult life.

Timeline by Pam Hackenmiller

A childhood of faith and love

Mary Campbell was born Oct. 22, 1945, in Santa Monica, California, the oldest daughter of Rae and Anthony Campbell. Her family moved to Long Beach, California, when she was 4 so her father could become an aeronautical engineer and work for the Douglas Aircraft Company.

Sr. Simone Campbell and her sister Katy dressed as cowgirls in about 1952. (Courtesy of Simone Campbell)

Campbell and her siblings — sister Katy, a year and a half younger than Campbell; sister Toni, 11 years younger; and brother Jim, 13 years younger — attended Catholic schools taught by the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. At her first Communion, she wrote in her 2014 book, A Nun on the Bus, she felt dramatically changed.

"There was this explosion for me," Campbell wrote. "At the time I didn't fully understand it. I just knew I felt different. It was if I was just being freed of something. That feeling, that sense, that definition of Eucharist, has never really left me, and I consider that one of the great graces of my life."

Campbell's faith would be sorely tested. When she was a senior in high school, Katy, then a sophomore, was diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma. The disease can be treated now, but in the 1960s, it was terminal, and Katy was given three to five years to live.

Katy came home from the hospital just in time for the family to be transfixed by the news coverage of the civil rights marches in Birmingham, Alabama, where protesting children were attacked by police dogs and sprayed by high-pressure fire hoses. Inspired by the young protesters, both teens dedicated their lives to civil rights, even as Katy's strength faded.

"It just seeped into my bones, this sense that I needed to live intensely enough for both of us, to channel her passion as well as mine. As she grew weaker, my commitment only grew stronger," Campbell wrote in A Nun on the Bus. "This wasn't a conscious process for me, at the time or since. But it certainly fed what has become my rather enthusiastic approach to life, and to living."

After high school, Campbell attended Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles, run by the same community that had taught in her schools. But it wasn't the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary that she was drawn to: It was the Sisters of Social Service, a society of apostolic life dedicated to social justice. Campbell knew the community well because they ran the summer camps she and Katy had attended as children.

"She's very much an extrovert, so she's very much the center of the crowd. She has an ability to get out and lead with courage and conviction. Which is a contrast, because she's also a very contemplative and prayerful person."

—Sr. Maribeth Larkin

Campbell would become a counselor at the sisters' camp, demonstrating her leadership qualities to camper Maribeth Larkin. Both grew up in Long Beach and attended the same high school, though at different times: Larkin's older sister was in the same class as Campbell's sister Katy.

"I remember her at camp, charging out to the front of a line of hikers," said Larkin, now the superior of the Sisters of Social Service. "She's very much an extrovert, so she's very much the center of the crowd. She has an ability to get out and lead with courage and conviction. Which is a contrast, because she's also a very contemplative and prayerful person."

On Sept. 8, 1964, a year after graduating from high school, Campbell entered the Sisters of Social Service. Novices were allowed to suggest their own religious names, and Campbell chose "Simone," a feminizing of Simon Peter, her patron saint.

"Like Peter, I can be impetuous," Campbell wrote in her latest book, Hunger for Hope. "I have been known to leap into situations and then have second thoughts. For me, this story [of Jesus walking on the water] demonstrates that in the face of 'headwinds' faith can make all the difference."

Four years after Campbell entered the community, Katy died.

The loss, Campbell said, didn't challenge her faith, but it could have caused her to leave religious life.

"The hard part was my parents and the little kids [Toni and Jim]," she said. "Leaving them to go back to my community house — that was hard, leaving them in their grief. I was worried for them. If it hadn't been for the little kids, I don't know if I could have gone back. But they had the little kids to keep them busy."

Campbell said she could especially relate to the passage in the first chapter of Philippians, where St. Paul writes that he wants to die to be with Christ but knows he needs to stay alive because there is so much work to do.

"That's where my sorrow went," she said. "Into the work. What I realized was that, in a way, I had picked up my sister's energy."

When Katy died, Larkin said, Campbell became twice as passionate.

"She was living for Katy," Larkin said. "That won't ever go away. It's an inspiration. It's an energy."

Campbell did go back to the community, and in 1969, they sent her to work as a religious education consultant for the Archdiocese of Portland, Oregon. While there, she volunteered to organize a tenants-rights effort at the state Capitol in Salem.

One of the legislators the group was lobbying asked Campbell about a point in the law, and she realized she didn't know.

"That led to the realization that I needed to be a trained lawyer if I wanted to continue doing this kind of work, which I was really enjoying," she wrote in A Nun on the Bus.

But first, she needed to take her final vows. The superior wasn't sure she was ready and had her move back to Los Angeles for closer scrutiny in the fall of 1972. While there, she worked at the Newman Center at Los Angeles City College, working with at-risk young adults. She made her final vows in 1973.

Sr. Simone Campbell in 1973 when she made her final vows with the Sisters of Social Service. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Social Service)

Following the Spirit

In 1975, Campbell began studying law at the University of California, Davis, and three years later, as a new attorney, she established the Community Law Center in Oakland to serve those who did not qualify for free legal services but didn't have enough money to hire a lawyer.

The practice began to specialize in high-conflict, low-income family law cases: abuse, dysfunction and heartbreak.

"I think it would be surprising for the public at large to know she was a family law attorney doing divorces," said Alice Beasley, an artist and attorney in Oakland who has known Campbell since the early 1980s. "But she made it a process to help people."

That process often involved being an advocate for the abusers in a relationship. Without advocates, Campbell said, abusers feel everyone is against them and lash out, perpetuating the cycle of violence. But when they feel they have someone on their side, the problems can often be worked out for the betterment of everyone.

"It's easy for the victim to get representation," she said. "But that doesn't necessarily change the situation. But if the abuser had representation, you could corral him, sit him down and make some sense out of what was going on. ... I like being able to run a comb through a tangled situation and help people make sense of it."

Campbell and Beasley started as colleagues, but they became close friends when she joined Beasley's sewing circle — a circle of friends that continues today.

"In the beginning, we may have all been attorneys," Beasley said. "It's a high-pressure career, and it was good to get together with other women and talk the talk."

Campbell loved to sew. She made all her own suits and did tailoring.

"I called it 'girls engineering,' " she said. "The more complicated the pattern, the happier I was."

Advertisement

The core of the sewing circle is still together today, though they are spread across the country. When Beasley had a brain aneurysm in 2019, the other members immediately flew to her side.

"They circled around me like you wouldn't believe," Beasley said. "They brought food, they took care of the house. They were fabulous."

They had drifted apart somewhat, but that incident brought them back together, and they now have a Zoom session once a month to ensure they stay close.

On Oct. 17, 1989, Campbell rode out the Loma Prieta earthquake with a client under a desk on the fifth floor of their old building as the ceiling fell around them. The 6.9 magnitude quake killed 63 people, including 42 who were crushed when a mile-long portion of the upper level of a double-decker highway collapsed — three blocks from where Campbell lived.

The experience gave her the realization that she needed a change. In 1995, she left the law center, unsure of what she would do next. The Spirit had an answer: She was elected superior of the Sisters of Social Service.

During those years in leadership, she learned not to ignore criticism, but to meditate on it.

"Criticisms only hurt if there's some truth to it," Campbell said.

So she reflects on what hurts until she understands the truth of it, allowing her to let go of the anger and grow.

"It used to be almost impossible," she said, laughing. But after more than two decades of practice, "now it's only moderately painful. It's hard to do, but it's the only way to be able to move forward."

"I joke that I don't like 'spiritual direction,' I like 'spiritual drift.' You need to wrestle with the substance of your life."

—Sr. Simone Campbell

After her five-year term as superior, Campbell took a sabbatical to figure out — again — what was next.

The Sisters of Social Service follow the Rule of St. Benedict, which calls for a monastic-style of life with daily prayer and the Liturgy of the Hours, so Campbell was familiar with meditative prayer, though there was no structure to her practice of it. She had begun to integrate a Zen framework into her meditation in the early 1980s, but the sabbatical allowed her to develop the technique of letting go and listening to the Spirit.

"I joke that I don't like 'spiritual direction,' I like 'spiritual drift,' " Campbell said. "You need to wrestle with the substance of your life. To care about the spiritual life requires engaging the reality of our lives. There's no managing it, and I'm always about managing. So I need to say, 'No, just let it go.' "

In 2000, during her sabbatical, one of her sisters approached her about taking over a program called Jericho, an agency lobbying the state legislature for those living at the margins in California. The job would combine the advocacy she had loved before law school with her extensive knowledge of the law and desire to help those who need it most. She said yes.

"The dysfunction drives you crazy, bad habits die hard, if at all, and trying to get enough people moving in the same direction to accomplish anything seems impossible — until it happens," Campbell wrote in A Nun on the Bus. "And all these flaws are distorted by politics, and then magnified by the fun house mirror held up by the media."

In short, the perfect place for a sister to have her ministry.

"She knows how to begin a dialogue between people who think they have nothing in common."

—Alice Beasley, artist and attorney who has known Campbell since the early 1980s

Beasley said politics is much like family law: "She's encountering the same thing. She's got people firmly entrenched in their side, and she knows how to begin a dialogue between people who think they have nothing in common."

In late 2002, as the United States prepared to invade Iraq, Mercy Sr. Kathy Thornton, who was then the head of Network, invited Campbell to join a peace delegation to the country, which had suffered under sanctions since the Persian Gulf War ended in 1991. The visits to hospitals, orphanages and churches taught her the most effective lobbying technique of all: telling the stories of those affected.

"She's setting up encounters that people don't realize are encounters," Beasley said. "She's finding ways for them to realize things like, 'Oh, this is what privilege means.' I wish she was president."

In 2004, Campbell was asked to apply for the executive director position of Network, a nonprofit similar to Jericho based in Washington, D.C., that lobbied Congress on national instead of state policy. Her first day was Nov. 1, 2004, the day before President George W. Bush was reelected.

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell speaks at a July 28, 2009, press conference promoting health care reform in the U.S. Capitol in Washington. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Simone (and Network) in the spotlight

Less than five years later came a legislative battle for the ages: health care reform.

Starting in the summer of 2009, Network staffers spent countless hours lobbying senators and representatives on the need for a health care system that provided both affordability and access, according to A Nun on the Bus.

In March 2010, the House was set to vote on the Senate's version of a health care bill that contained similar, but not exact, language that has been used for decades to prohibit using federal funds to pay for abortions. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops endorsed the House bill, which used the decades-old language, but not the Senate version, despite assurances it created the same prohibition.

On March 13, 2010, the Catholic Health Association announced its support of the Senate bill, an important endorsement that carried both the stamp of approval by its health care providers, who at the time saw one of every six hospital patients in the United States, and by extension the communities of sisters that run or sponsor most of them.

Within hours, Network issued a statement supporting the association's stance, then began a sign-on letter to show the broad level of support. When released, the letter contained the signatures of 59 sister leaders representing thousands of sisters, including LCWR leadership. Their endorsement gave pro-life representatives in the House the reassurance and political cover they would need to vote yes on the bill.

The media pounced on the differing stances between sisters and bishops, and Campbell did 33 interviews in five days, including one on Fox News in which she explained the sisters weren't choosing between health care reform and protecting the unborn because the bill did both.

Then-President Barack Obama talks with Sr. Simone Campbell in the Oval Office May 30, 2013, at the White House. (CNS/Pete Souza, The White House)

On March 21, 2010, the House voted to adopt the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act — known as "Obamacare" — bringing health insurance to millions of people. President Barack Obama thanked Campbell at the signing celebration and said Network's letter was the tipping point, she wrote in A Nun on the Bus.

"The Affordable Care Act was such a big step forward — those are so rare," Campbell told GSR. Usually, progress requires tiny, incremental steps, a piece at a time, which can be frustrating, she said.

The health care victory raised Network's visibility dramatically, but it also brought them to the attention of the Vatican, and the organization was added to the doctrinal assessment of LCWR, which had begun in 2009. Network and the communities included in its sign-on letter also received hundreds of calls and letters, calling them "baby killers" and saying they were not really Catholic, according to A Nun on the Bus. Bishops told congregations of sisters they couldn't use diocesan property for events or advertise vocation days in diocesan papers.

Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell, executive director of Network, applauds during the group's 40th anniversary celebration April 14, 2012, at Trinity Washington University. (CNS/Nancy Phelan Wiechec)

On April 18, 2012, two years after the Obamacare fight, Network found itself not just facing down the U.S. bishops, but the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: Rome announced it was demanding massive reforms at LCWR and appointing bishops to oversee the process.

The report said a bishop had presented evidence to the doctrinal congregation about Network but never made public what it was, and no sanctions were ever issued on the organization.

"The bishops were upset because we won on health care. ... It's the old 'create a villain and attack.' But they picked the wrong target."

—Sr. Simone Campbell

"There were two dynamics at work. One was the pedophilia — [the bishops] felt beset, so they lashed out at something else," Campbell said. "The other aspect, at least in regard to Network, was the bishops were upset because we won on health care. ... It's the old 'create a villain and attack.' But they picked the wrong target."

Within a month, Network staffers had determined that the best way to leverage the sudden national attention onto their active battle against the 2013 federal budget proposed by Wisconsin Rep. Paul Ryan was with a road trip, and Nuns on the Bus was born.

On June 18 — just two months after the Vatican announcement of its reforms of LCWR — the first Nuns on the Bus tour began. The trip was planned as a way to show the plight of those who would be hurt by the Ryan budget and lobby its congressional backers along the way, but what it turned into was a media juggernaut, which led to even more media attention, which led to Campbell giving an address at that year's Democratic National Convention.

There were appearances on "The Colbert Report," "The Daily Show with Jon Stewart" and "60 Minutes," and interviews in The New York Times, The Washington Post and Rolling Stone magazine.

The bus was also a fundraising boon: Running on fumes before the Vatican announcement, Network raised $150,000 in 10 days following the announcement of the bus trip, Rolling Stone reported.

"Network will never be the same," Campbell told the magazine. "We've blown up our organization."

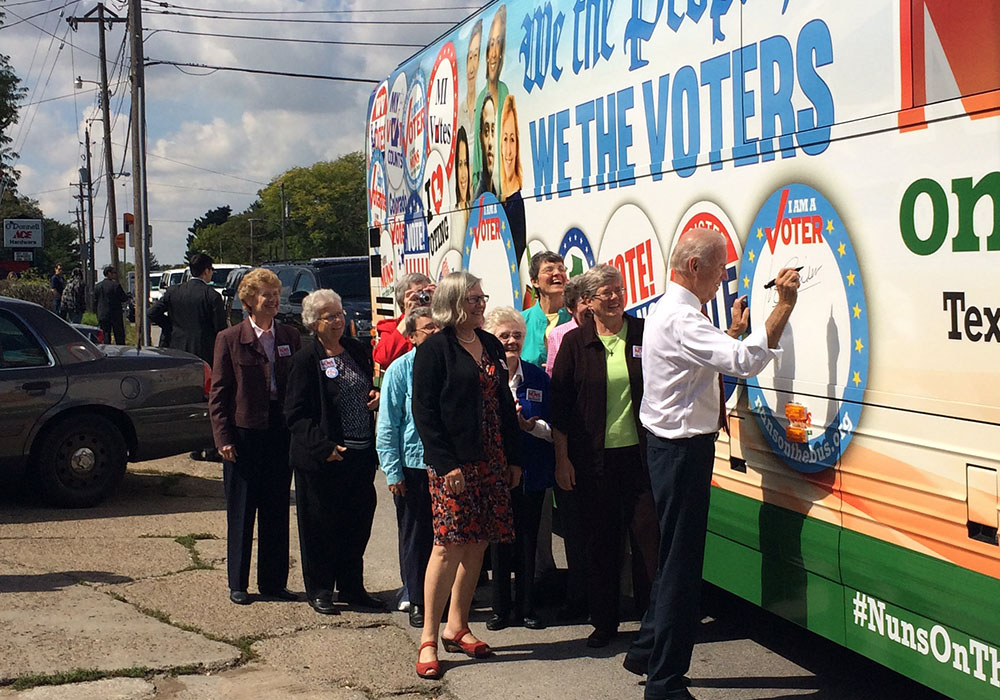

The bus tours and media attention continued, with a tour every year from 2013 to 2016, another in 2018 and a tour in 2020 that took place entirely online because of the coronavirus pandemic. Those tours focused on immigration reform, "dark money" in politics, bridging divides, income inequality, tax policy and multi-issue voting.

Vice President Joe Biden signs his name to the Network Nuns on the Bus official vehicle after speaking at the kickoff rally in front of the Iowa State Capitol in September 2014. Some of the Nuns on the Bus, including Sr. Simone Campbell, in red shoes, stand behind him. (Courtesy of Network)

Then, on Oct. 20, 2020, days before the virtual bus tour wrapped up, Campbell announced she would leave Network at the end of March.

She almost left two years before.

"The first time I mentioned it, the board was shocked," Campbell said. "I mentioned it first in 2016, thinking that if Hillary Clinton had been elected, I would have stepped down in 2018 and let the new executive director get ready for the 2020 election. But when Donald Trump got elected, I just couldn't do it. It was too important to stay and fight."

On March 22, Network announced that Mary Novak, a lawyer, chaplain and activist, would become executive director April 1.

"We're much more than me," Campbell said. "We have all the state teams now, all the lobbyists on the Hill. It's much more than me."

"Network is in a good place. It'll be an adjustment, but they'll do great."

"If Hillary Clinton had been elected, I would have stepped down in 2018 and let the new executive director get ready for the 2020 election. But when Donald Trump got elected, I just couldn't do it. It was too important to stay and fight."

—Sr. Simone Campbell

Larkin said Campbell, now 75, will someday have to ease up her schedule — Campbell told America magazine in December that she had flown more than 100,000 miles a year domestically in the eight years before the pandemic.

"I don't think her intention will be to slow down, but she's going to," Larkin said. "She's not going away. Just because of the nature of who she is, whatever she's doing will be recognized. That's what happens."

Campbell insists she's ready to slow down, at least for a while. The pandemic has meant she now has time to go to the farmers market, she told America, and she's looking forward to a sabbatical of meditation and reflection.

"It's all surprise. It's the Spirit. I'm just so aware of the gift of all this," she told GSR. "And it's been fun in the process. I have to say it's been kind of wild."