(Unsplash/Jonas Jacobsson)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

With all the reviews in the global press about summertime and wintertime reading, our thoughts turn to books. Are you looking for a good book to take with you on retreat? The scope of the panelists' suggestions was very wide when we asked them for recommendations with this month's question:

What is a book you have read lately that is shaping your response in ministry or in religious life?

______

Catherine Scholastica K. Mutua is a Religious of Notre Dame of the Missions from Kenya. Her academic background was in theology and religious studies, peace and development, with certification in early childhood and Scripture. Her first ministries were in teaching nursery school and coordinating the oblates. Recently, she returned from the Philippines, where she had been living and working for 21 years, primarily involved in peace-building and development programs. She hopes to continue similar programs in the Machakos Diocese in Kenya.

Catherine Scholastica K. Mutua is a Religious of Notre Dame of the Missions from Kenya. Her academic background was in theology and religious studies, peace and development, with certification in early childhood and Scripture. Her first ministries were in teaching nursery school and coordinating the oblates. Recently, she returned from the Philippines, where she had been living and working for 21 years, primarily involved in peace-building and development programs. She hopes to continue similar programs in the Machakos Diocese in Kenya.

I was reading a book by Joyce Rupp, The Cup of Our Life, when we got this assignment. I felt this book was so appropriate for me during this time when I have been looking back at my life in our renewal program. This has given me opportunity to reflect where I am now and where the future calls me after many years of mission in another country.

A few years ago, when I was teaching nursery school, we used small blue plastic cups. This was a good size for the children, and being plastic, they reduced the chances of breaking. Sometimes we the staff used the same cups. One day, I was outside cleaning when a man approached me; he did not seem right in the head and asked for some water to drink. I took one of our blue plastic cups and poured water from the jug and went out to give it to him.

(Pixabay/Holger Langmaier)

To my surprise, when I extended the cup to him, he looked at the cup, and he looked at me without saying a word. I held the cup toward him and I said, "Here is the water you asked for." Eventually, he said to me, "I see, you are giving me water with the plastic cup because to you, I look like a mad person." I replied to him that we too use the same cups for everything. With one final look at me with my cup, he left.

We all have a particular cup or mug we like. Each of us has our own reason why we like that particular cup and not another cup. Probably it has a story how it was acquired, and that story makes it very special to the owner. What is the story behind your special cup?

(Pixabay/Jeon Sang-O)

After all these years, I see my life as a cup: beautiful but cracked and chipped, with a broken handle. This reminds me of my humanness. With many years of use, a cup is bound to slip and fall, and if it does not totally break, one continues to use it.

Joyce Rupp's book helped me to see many facets of my religious life that I had not seen before. Reflecting on my life over the last 25 years, I see these same characteristics that Joyce mentions in her book. The different symbols reflected in one cup echo the different stages of my living religious life. On Page 135 and following, Joyce talks about the "blessing cup." Although the whole book has many lessons for my life, those particular pages have helped me to find blessings in various ways that I have lived my life and continue to live. Quoting her: "Anyone and anything that brings good or God-ness into our lives is a blessing."

At this point in my life, I continue to live the cup of our life and nurture the lessons that are presented in ordinary symbols like a cup.

Mafalda Maria Gaudêncio Franco Leitão is from Lisbon, Portugal, and is a member of the Congregation of Servants of Our Lady of Fátima. With a background in educational sciences, her special research interests include education for sustainable development (training teachers in Portuguese-speaking African countries on water issues); education for global citizenship and integral education; and climate migrants and refugees. She taught physics and chemistry in secondary schools and worked in youth ministry in various parishes and dioceses. Currently, she serves as general counselor for her congregation.

Mafalda Maria Gaudêncio Franco Leitão is from Lisbon, Portugal, and is a member of the Congregation of Servants of Our Lady of Fátima. With a background in educational sciences, her special research interests include education for sustainable development (training teachers in Portuguese-speaking African countries on water issues); education for global citizenship and integral education; and climate migrants and refugees. She taught physics and chemistry in secondary schools and worked in youth ministry in various parishes and dioceses. Currently, she serves as general counselor for her congregation.

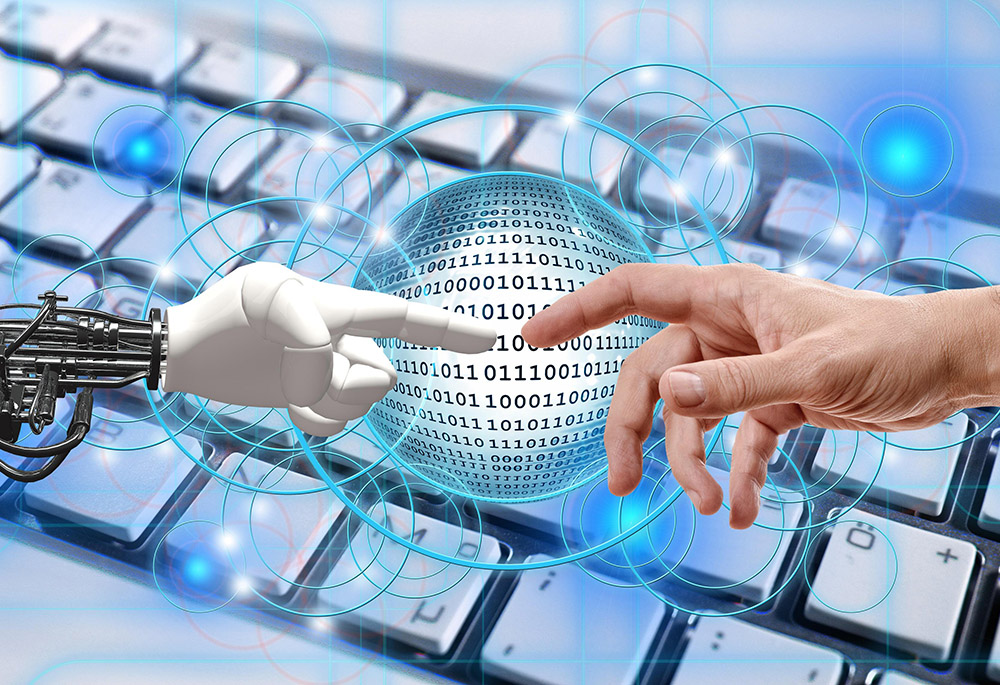

I bought Machines Like Me in an airport when I traveled to visit our community in Brussels. The reading was amazing, sometimes disturbing and surprisingly fun. In fact, Ian McEwan is a master of storytelling.

This novel is set in an alternative 1980s London, where Charlie has just purchased Adam, one of "the first truly viable manufactured human with plausible intelligence and looks, believable motion and shifts of expression," and is falling for Miranda, the young neighbor upstairs.

The plot led me to think about the possibility of humans and machines sharing life — dreams, problems, secrets, intimate experiences — and, even more, how different people — in this case, a robot — may change our routines, visions, and perceptions when entering our normal and linear life.

The narrative is dynamic with complex moral problems, uncertainties about the characters, constant turning points that reconfigure the plot, historical fictitious references and especially the ambiguous figure of Adam, who made me think about what is human and what is not.

This book leads me to reflect deeply about what our religious response is in controversial issues. This issue seems especially striking to me because I have a background in science (physics teaching) and because of my current ministry at the Luiza Andaluz Knowledge Center, which seeks to find new languages for a transformative evangelization in our contemporary life.

(Pixabay/Gerd Altmann)

First, the triangular relationship of Charlie, Adam and Miranda broadened my view about dealing with unlike and complex situations: relations with what is different, interculturality — for example, members of the LGBT community. For me, the reading of Acts 11:1-19 will never be the same: "So then, even to Gentiles God has granted repentance that leads to life." In this complex time, what is the Spirit telling me and us about broadening our minds and hearts?

Secondly, our closest and daily life relation with complex and sophisticated machines is not sci-fi anymore. Adam's unbelievable behavior as a machine with feelings, ability to love and ability to test the moral decisions of humans reminds me of the advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and the specific challenges future generations will face.

In fact, this tests my responsibility as a member of the church and a religious with leadership duties as assistant general in taking "the first step" (Evangelii Gaudium, 24) in a community of missionary disciples that desires a church that "goes forth" spreading the Gospel where it is not known.

Machines Like Me is a novel, but it describes reality. As Charlie says: "The present is the frailest of improbable constructs. It could have been different."

My response to the new demands in our reality is only beginning.

Advertisement

Sue Scharfenberger is an Ursuline Sister from Louisville, Kentucky. An educator, she ministered in rural Mississippi and for the last 42 years has been with the people in the coastal region and the Central Sierra of Peru. Her ministry has been with circles and communities of women around issues of empowerment, nonviolence and leadership. She has served as facilitator for various religious communities in Central and South America and the Caribbean and currently represents her congregation as mission promoter with parents and teachers at Santa Angela Merici School, founded by the Ursuline Sisters of Louisville in 1965 in Carmen de la Legua, Peru.

Sue Scharfenberger is an Ursuline Sister from Louisville, Kentucky. An educator, she ministered in rural Mississippi and for the last 42 years has been with the people in the coastal region and the Central Sierra of Peru. Her ministry has been with circles and communities of women around issues of empowerment, nonviolence and leadership. She has served as facilitator for various religious communities in Central and South America and the Caribbean and currently represents her congregation as mission promoter with parents and teachers at Santa Angela Merici School, founded by the Ursuline Sisters of Louisville in 1965 in Carmen de la Legua, Peru.

My encounter with the "Universe Story" happened years ago while reading Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. And then, in the last several years, I had become more acquainted with Brian Swimme and Thomas Berry, and my fascination with the connections in the unfolding of this great mystery of becoming found a new place in my thoughts and reflections.

However, it was Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer that put a totally different perspective on my relationship with the part of the universe that touches my life daily and invites me to a communion of being. The concern is no longer for "the environment" in the abstract. No, now I have been introduced to pecans and strawberries, asters and goldenrod, maple sugar, and sweetgrass. They have come alive within the Indigenous communities of which they form a part of life. And their personalities are both challenging and enriching.

Personalities, yes. Because nothing is just an "other." All life is connected, an affirmation I have always believed but that now has an enormously different ring to it.

(Pixabay/Ralphs_Fotos)

As I have come to better understand the lessons we need to learn from Indigenous communities, my spirit aches to know, to touch, to feel, and to share their wisdom without invading their space or letting curiosity be the mover. The traditions and customs and wisdom expressed in Braiding Sweetgrass are foreign to anyone like me who has grown up and lived most of my life in the city. Still, I am assured that even I can grow into caring and tenderness, wisdom and communion as I let my imagination and my heart embrace the wisdom of the Quechuas and the Aymaras, the Asháninkas and the Shipibo, Peruvian Indigenous communities.

None of these communities are part of the book, of course, but one could easily liken their stories to that of the Potawatomi or the Nanabozho Indigenous communities encountered in Braiding Sweetgrass.

My imagination has at times been an obstacle to my ability to put ideas into words and words into projects. But I have been encouraged by Braiding Sweetgrass. I still need to carve out time to get to know the wild and the beautiful growth that is in the patch of earth in my back patio. My priorities need to change. I know that. But as I touch, feel, water and care for the unruly and the tame in my backyard, I am amazed and delighted with their friendship and personalities. They continue to invite me, challenge me, and comfort me as I seek out the unfathomable mystery of the universe and her story.

These recent adventures I share with the school community of which I am a part. Pure invitations, but that is how curiosity moves us and others into an experience that ultimately leads us to create a more caring and loving community of life.

(Pixabay/Kranich17)

Beth Murphy is a Dominican Sister of Springfield, Illinois. With a background in journalism, communications and theology, she has worked mostly in communications ministry: diocesan communications director; manager of the National Coalition for Church Vocations' publishing arm, Communicators for Women Religious; and communications director for her religious community. In other ministries, she taught junior high, resettled Iraqi refugees in Detroit, and worked in a mostly Mexican parish in Chicago. She has been deeply engaged with the Iraqi Dominican sisters and friars and has traveled to Iraq four times.

Beth Murphy is a Dominican Sister of Springfield, Illinois. With a background in journalism, communications and theology, she has worked mostly in communications ministry: diocesan communications director; manager of the National Coalition for Church Vocations' publishing arm, Communicators for Women Religious; and communications director for her religious community. In other ministries, she taught junior high, resettled Iraqi refugees in Detroit, and worked in a mostly Mexican parish in Chicago. She has been deeply engaged with the Iraqi Dominican sisters and friars and has traveled to Iraq four times.

It seems everyone I know has read or is reading Braiding Sweetgrass, the gorgeous memoir by Robin Wall Kimmerer. I was well into Braiding Sweetgrass when I picked up Diarmuid O'Murchu's 1997 magnum opus Quantum Theology and became attuned to their resonances of spirit, wisdom and hope.

I might have guessed sooner from their subtitles: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Kimmerer) and Spiritual Implications of the New Physics (O'Murchu). Read together, they act on my psyche and soul the way vinegar acts on baking soda: explosively. Together, they are catalysts for a new perspective that is still unfolding for me.

Quantum Theology puts a subject that has never held my interest — physics — in dialogue with, one might say, my "professional" life of 40 years. That is already clear, though I'm not yet a third of the way through Quantum Theology. Like Sweetgrass, O'Murchu has a constellation of "sisters" too — not corn, beans and squash, but theology, spirituality and quantum physics. And like Thomas Aquinas, Teilhard de Chardin, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, O'Murchu draws on a long tradition of theology as a contextual, interdisciplinary science.

(Unsplash/Ben Wicks)

As Kimmerer faced critics and skeptics when she told her college adviser she wanted to study science to learn about beauty, O'Murchu is challenged by the ecclesial establishment. Their insights are challenged because they understand humanity is at a crossroads requiring a wider horizon for dialogue than either old-school botanists or the patriarchal church appreciate. In the face of the protestations of some scientists and theologians, O'Murchu's work makes space for an interdisciplinary conversation among scientists, theologians and mystics. Such a conversation requires study and meditation, he says. It needs theology's reason and the mystical traditions of the world's faiths. This is "a matter of letting go, releasing the props, the attachments, the will to power and control, which has so dominated our Western mind and psyche."

Kimmerer observed that you have to speak the language of those you want to listen to you in order to be heard. She translated the wisdom of her Indigenous traditions into prose that is deepening my appreciation of reciprocity as a mode for living religious and ministerial life.

O'Murchu's work is accomplishing something similar for me. God is inherently relational; hearing God's message requires a relationship with God, and a relationship with God requires relationship with the things of God. For Kimmerer, this garden of relationality is the wisdom of her ancestors, fields of asters and goldenrod, and botanists' laboratories; for O'Murchu, it's spirituality, mystical tradition, and particle accelerators. Together, they are catalysts for a desire to learn the language that will most effectively speak to our age about God and the things of God. "Contemplata et aliis tradere," our Dominican motto says: to contemplate and share the fruits of contemplation.

Spirituality is indigenous to the human person, not the provenance of formal religion only, O'Murchu argues. Kimmerer's gift of Indigenous wisdom widens our horizon to see the spiritual gifts of "our older siblings the plants." Reading them together is widening my consciousness and expanding my appreciation of scientific and spiritual truths both in the world I perceive and in the one I can't. This three-way conversation leads, I hope, to the Sacred Heart of Creation.