Shannen Dee Williams, associate professor of history at the University of Dayton, speaks to her students during a class April 21 in Dayton, Ohio. Williams spent 14 years researching America's Black nuns, and her history of them, "Subversive Habits," will be published May 17. Williams found that many Black nuns were modest about their achievements and reticent about sharing details of bad experiences, such as encountering racism and discrimination. (AP photo/Aaron Doster)

Shannen Dee Williams was scrolling through microfilm in 2007, looking for a suitable paper topic for her graduate seminar on African American history at Rutgers University, when a newspaper story caught her eye.

In the years since, she has said that had she known what she was getting into, she would have kept scrolling. But she didn't. Instead, she read the 1968 story about the very first meeting of the National Black Sisters' Conference and stared at the photo of someone she had never seen before: a Black nun. Intrigued, she read on.

How was it possible, Williams thought, that a Black woman who grew up Catholic was unaware of the existence of Black sisters in the Catholic Church? Her mother, who had attended sister-run Catholic schools, had also never heard of Black sisters.

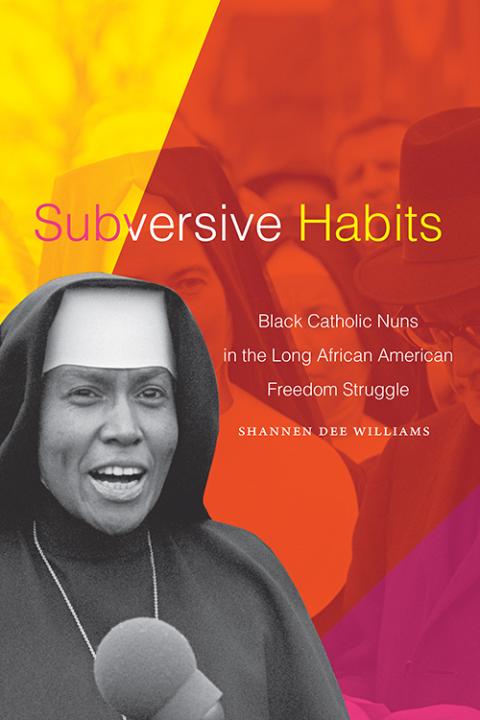

The cover of "Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle" (Courtesy of Duke University Press)

Now, 15 years after that day with the microfilm, Williams can hold in her hands the answer to that question in the form of her book, Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle, released this month by Duke University Press.

Now that Williams, an associate professor of history at the University of Dayton, has finished the project, would she still keep scrolling if she could do it over again?

At first, she's not sure.

"There are moments I still feel that way," Williams told Global Sisters Report. "But I'm very happy I've completed the project. I know that it matters. But there certainly has been a cost to doing this work."

As she wrote in America magazine: "When I submitted the final manuscript for Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle this past winter, I looked up from my computer screen ... walked to my room, sat on my bed and cried for three hours straight."

Williams, after a pause, says she would do it all over again, if only to ensure the stories of Black Catholic sisters get told, even the ones she could not include in the book.

"I only cite about 75 interviews, but I did about 150," she said. "Many are stories I can't tell — the sisters asked that I keep them private, but they wanted to tell me because they had to get them off their chests. ... There's a lot of testimony I'm going to have to take to my grave."

Some didn't want their stories told because they were too painful; others, because they fear backlash if they make public what their white sisters did to them, especially now that they are elderly and dependent on their care. One asked that her story not be told because she has a sibling who is passing as white.

But the stories also tell of a faith that never broke.

Early members of the National Black Sisters' Conference outside the conference headquarters in Pittsburgh in the early 1970s. (Courtesy of Sisters of Charity of Nazareth)

"The reality is it's been a beautiful journey," Williams said. "It's a proud history, a beautiful history, but it's also a painful history."

The extensively researched book, which includes more than 100 pages of citations, tells the history of Black sisters in the United States, from the "few girls of color desiring religious life" and their 1819 attempt to join the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Jesus to 2018, when the National Black Sisters' Conference honored Patricia Grey, formerly Mercy Sister M. Martin de Porres, as its foundress at its 50th anniversary.

The stories largely have been untold, Williams said, but there are many more for which it is too late.

"It remains a challenge for me as a scholar to think about how many women were allowed to die and how many women's stories that I missed, how many Black sisters' stories we've lost because so many scholars did not deem their stories worthy enough to be preserved," she said. "But if I'm hopeful of anything, it's that the next generation of scholars will continue this work."

Williams was given unprecedented access to some congregational archives, especially after her 2016 presentation to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious' annual assembly.

Shannen Dee Williams addresses the Leadership Conference of Women Religious assembly in Atlanta in August 2016. (CNS/Georgia Bulletin/Michael Alexander)

Margaret Susan Thompson, an associate professor of history at Syracuse University who studies Catholic sisters and race in the United States and is an associate with the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, told GSR that the comprehensive story of Black Catholic sisters in the United States has never been told until now.

"She's the first person to really explore the history of African American women religious, period. There've been articles, dissertations and so forth, but she's doing some very important work here," Thompson said. "Especially because it's across communities, both historically African American communities and historically white communities."

Thompson said there has been notable scholarship on Black sisters, such as Diane Batts Morrow's 2002 book, Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time, which examined the Oblate Sisters of Providence from 1828 to 1860, and work by Cecilia Moore, but it has been narrow in scope.

Williams has "a comprehensive vision that we haven't had before," Thompson said. "She gives us the basis for comparing across time and across congregations. It may be the first, but it shouldn't be the last."

Shannen Dee Williams, right, presents Mercy Sr. Cora Marie Billings with an honorary doctorate at Villanova University's May 2019 commencement ceremony. (Courtesy of Villanova University)

Bettye Collier-Thomas, author of Jesus, Jobs, and Justice: African American Women and Religion, in a review calls Subversive Habits "sweeping in its scope, exhaustively researched, and balanced in presentation" as well as "a seminal history of Black Catholic Nuns and their struggle for equality and justice in the Catholic Church."

Williams said her book will undoubtedly make some uncomfortable, as it shows how religious life was often a bastion of white supremacy and segregation. It details how white communities rejected Black women, told them they could only apply to Black communities, or discouraged them from joining religious life; how Black communities were shunned or attacked; how congregations kept written and unwritten policies excluding women of color for decades after the civil rights battles of the 1950s and '60s; and how Black sisters who did join white communities were subjected to racist policies and treatment. Many congregations owned enslaved people until it was outlawed with the Civil War.

"I have to believe that's why it's taken so long to write this history," Williams said. "I think a lot of people don't want to talk about it because it's very dangerous to the narrative we've been told."

Advertisement

Williams said many congregations have begun to reckon with their pasts, but many have not.

"There are many communities with histories rooted in slavery who have not apologized, who have not taken even the first step forward in acknowledging their history in any way," she said. "We are going to have to reckon with this, and it's going to be terrible. Reconciliation is our greatest sacrament, but you don't get to reconciliation without telling the truth."

The truth, she said, is not something to be afraid of.

"If we are truly Catholic, we have to understand the truth cannot destroy us. It can only make us better," Williams said. "It can only force us to uphold our teachings."