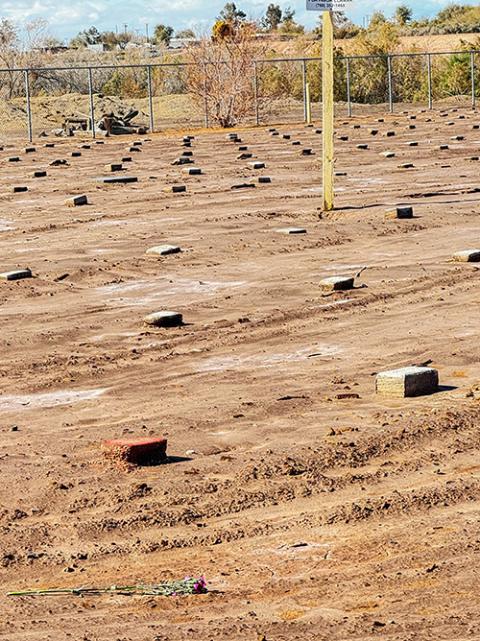

Sr. Clara Malo Castrillón, provincial of Mexico's Society of the Sacred Heart, looks through an opening in a fence where you can see tombs fenced off from the rest of Terrace Park Cemetery in Holtville, California, during a Feb. 7 stop. Sisters stopped to pray and threw flowers over the locked fence toward the bricks that serve as tombstones where remains include those of anonymous migrants. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Sr. Clara Malo Castrillón peered through the locked gate and the sight on the other side made her cry.

Through a small opening, she could see the bricks, some clay-colored, others white, on the arid landscape. They were neatly lined in clean rows, hundreds of them. But unlike the other tombs in the main part of Terrace Park Cemetery, there were no names, no flowers, no grass, no words of love from family scribbled on the bricks that served as tombstones. The only greenery came from the "privacy fence," the green plastic that kept out of sight the sterile-looking tombs with "Jane Doe" or "John Doe" written on them.

There's no signage to point out who's buried there, but the arid field is the final resting place for many border crossers who died in anonymity in the surrounding area, laid to rest with others who couldn't afford a cemetery plot.

"A potter's field with a fence," said Sr. Marian Schubert of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange, California, who along with Malo formed part of a group made up primarily of Catholic sisters who stopped by with flowers and prayers Feb. 7 to pay their respects.

Sisters gather at the entrance of the Terrace Park Cemetery in Holtville, California, Feb. 7, before a procession toward a part of the facility where anonymous migrants are buried. Sisters sang, prayed and threw flowers toward the tombs that are fenced off from the rest of the cemetery. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

The stop was one of several during a five-day "border pilgrimage" in early February to discern how religious communities can respond to situations involving migrants and refugees.

Holtville, where the cemetery is located, is about 10 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border and some 125 miles south of San Diego. The field, which contains remains that did not have identification on them when they were found nearby, has been written about in the Los Angeles Times as well as in The San Diego Union-Tribune. The San Diego newspaper said in its 2016 article that as immigration authorities intensified efforts to catch border crossers in 2009, migrants began traveling closer to the Imperial Valley, a desert area where Holtville is located. Though they crossed the border undetected, exposure to the elements in the terrain may have led to death for those buried there.

'Even in death, they have a wall to keep you out.'

—St. Joseph Sr. Marian Schubert

"These are the people who survived the whole journey and crossed just to find death in a new world," Malo said Feb. 9, reflecting on the stop at Terrace Park.

Malo, provincial of Mexico's Society of the Sacred Heart, wept as she rested her head against the fence during the visit.

With other sisters, she walked in procession toward the field and sang. Some sisters placed the palm of their hand against the fence, near a sign that read, "No trespassing," before throwing carnations over the barrier, hoping the flowers would land near the tombs.

"Even in death, they have a wall to keep you out," Schubert said during a Feb. 9 reflection at the Franciscan School of Theology at the University of San Diego, where the sisters gathered to talk about the experience.

A handful of carnations that sisters threw over a fence Feb. 7 fell near bricks that serve as tombstones in a field where anonymous migrants are buried at Terrace Park Cemetery in Holtville, California. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

A video by the Union-Tribune says the plot opened in 1994 but burials in the field stopped in 2009 and unidentified remains of presumed migrants found in the same fashion nowadays are cremated and buried at sea. It's hard to pin down a number of how many have died in such a manner, but the International Organization for Migration, which began keeping track of missing migrants since 2014, has recorded 5,289 people who have gone missing since that year along the U.S.-Mexico border. Many are presumed dead.

The most common causes of death the International Organization for Migration lists are harsh environmental conditions, drownings and hazardous transport.

"For every person included in the Missing Migrants Project data, there is a family awaiting news of their loved one and affected by their loss in a multitude of ways," the International Organization for Migration says on its missing migrants website.

St. Joseph of Orange Sr. Herlinda Ramirez thought about the families of those buried in Terrace Park, who "don't know what happened" to their loved ones and may never get an answer.

"They are not exactly lost," Ramirez said of those buried there. "However, they don't have a name."

She, too, thought of the fencing around tombs as yet another wall, one of many barriers for migrants that the sisters saw near the border. Walls surround them "even in death," one sister said.

At various points south of San Diego, the group of sisters visited the U.S.-Mexico border wall, which is not contiguous due to terrain and other issues. They made a stop at El Parque de la Amistad (Friendship Park) near the San Ysidro Port of Entry. While the U.S. side of the wall has surveillance and is not open to the public most of the time, the Mexico side in Tijuana has its park open to the public and is adorned with colorful sculptures. The wall is painted with bright colors and images, including a heart that says, "LOVE."

Sr. Mary Grace Ramos, left, and Sr. Florence Anyabuonwu, both Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange, California, walk out of Terrace Park Cemetery in Holtville, California, Feb. 7. They were part of a group of women religious who prayed near tombs fenced off from the rest of the cemetery that include remains of anonymous migrants who died nearby. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

But Ramirez said there's nothing that can make a wall, including a fence surrounding the tombs of the unknown, pretty because of the sentiment behind it.

"The pain is there, the suffering of man is there," she said.

Social Service Sr. Anne Carrabino said the idea of a rust-colored wall on the southern border comes from "the same thinking that drove and created the cemetery: that these are not people."

Society of the Sacred Heart Sr. Mary Bernstein said what was striking for her was the separation between the two sets of tombs at Terrace Park.

"Looking through the crack, to be on the side that had the green, and the water, the trees, and the flowers ... looking through the crack at the dirt and the stones and just the disrespect," she said. "When trying to give respect is a disrespect by preventing [others] from seeing it."

Advertisement

Holtville is not alone when it comes to dealing with such issues, particularly as migration rises around the world and so do migrant deaths. The International Organization for Migration has tracked more than 64,000 missing migrants around the world since 2014, with the bulk of them — more than 29,000 — missing in the Mediterranean.

In the U.S., in January 2023, The Texas Tribune published a story of a "border graveyard," following community outrage after videos were posted on social media of tombs of unidentified migrants at the Maverick County Cemetery in Eagle Pass, Texas. They showed a mound of tombs with white PVC pipes sticking out in the shape of crosses. It happened during a time when the border town was said to be experiencing a high number of migrant crossings that in many cases lead to deaths.

The way the remains of unidentified migrants are treated is a worldwide issue. It led Algerian artist Rachid Koraichi to do something about those whose bodies wash up after drowning in the Mediterranean, a place Pope Francis has called a huge "cemetery." Koraichi, whose 16-year-old brother disappeared in the deadly body of water, bought land in Tunisia after hearing that the migrant dead who turn up near the coastal community of Zarzis were interred in a public landfill site.

He used that land to create the Garden of Africa, a cemetery where the bodies of the unknown that now appear on that shore are buried.

"I think that whoever doesn't respect the dead doesn't respect the living either," he told The Markaz Review in 2023.