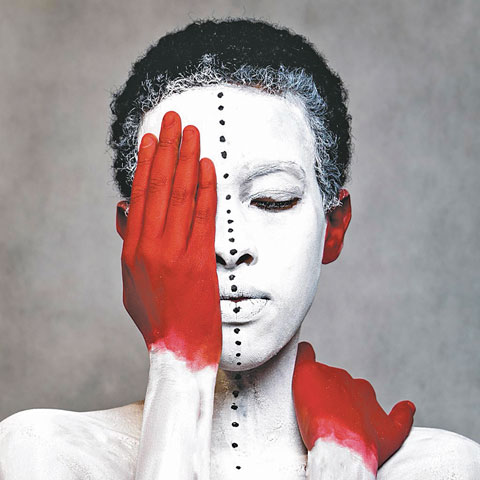

A print from "The 99 series" (2013) by Ethiopian photographer Aida Muluneh. The series appears in the purgatary section of the exhibit "The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists." (Courtesy of National Museum of African Art)

Evidently artworks, like souls, can migrate and see dramatic changes in their eternal luck.

When it was installed at the Savannah College of Art and Design late last year in a Dante-themed exhibit, British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare's installation "How to Blow Up Two Heads at Once (Gentlemen)" appeared in the purgatory section. In the show's Washington iteration on the National Mall, the work is now condemned to hell.

The work -- which depicts two headless figures in elaborate garb pointing revolvers at where each other's head ought to be -- is sufficiently violent to merit a demotion. And the section that houses it at the National Museum of African Art's exhibit "The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists" (through Nov. 1), like the hell of medieval Italian poet Dante's famous work, features the warning, "Bid hope farewell, all ye who enter here."

But the installation's change in status, as well as the exhibit's broader focus on contemporary, and often secular, responses to a classical, religious work like Dante's, point to an elasticity when it comes to interpreting Divine Comedy.

Consider that William Butler Yeats referred to Dante as "the chief imagination of Christendom," and in 1921 Pope Benedict XV said the medieval poet is "among the many celebrated geniuses of whom the Catholic faith can boast." So what can it mean for this exhibit -- the first to fill the National Museum of African Art's entire floor space, in which viewers literally descend from the exhibit's heaven to purgatory to hell sections -- to suggest that those concepts laid out in Dante don't belong to the Catholic church?

Writer and critic Simon Njami, who curated the exhibit and wasn't available for interview, recently told Elena Goukassian of The Washington Post Express that the exhibit aims to take heaven, purgatory and hell "out of the cradle of the church and to make them something everybody can live with."

In her article, Goukassian framed it as choosing "to focus on the universal nature of Dante's epic poem rather than its Catholic overtones."

Most of the pieces in the exhibit don't feature overt Christian content or themes. "Heaven," for example, contains a work by Egyptian artist Ghada Amer titled "The Blue Bra Girls" and an installation by artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah, which consists of high-heeled shoes on Islamic-styled prayer mats.

But there are some standout works that do portray religion literally, such as South African artist Andrew Tshabangu's "From on Sacred Ground" photography series of arresting images of prayer, stations of the cross, and churches.

Dimitri Fagbohoun's "Refrigerium," whose materials include "wood confessional, broom, book, screws, ceramic objects, electroluminescent paper, frame, inverter, and video with sound," allows visitors to enter two sides of an apparent confessional booth. Spelled out in nails is the inscription "Lord have mercy."

But when asked about the secular works, and the context of wrestling hell out of the church's cradle, experts are divided on what that sort of program means, and what it is likely to accomplish.

When he describes the ways that Dante "moves easily outside the church," Phillip Thompson, executive director of Emory University's Aquinas Center of Theology, quotes Catholic theologian David Tracy's description of the poet's work as imbued with a "surplus of meaning" that "contains its own pluralism and encourages a pluralism of readings."

"The same Dante who provided a template for Thomas Merton's Seven Storey Mountain and so many plays, movies and novels is also inspiring this exhibit of African artists," Thompson said.

In the National Museum of African Art exhibit, wall labels refer to a variety of ways in which the artists have responded to the concepts Dante laid out in the Middle Ages: "paradise -- or heaven -- can be the power of women standing up for themselves"; "heaven is love, motherhood, and dance"; "purgatory is connected to the condition of immigrants"; and "hell ... can even be embodied in a beached whale." In the first room of the exhibit, the artist Bili Bidjocka is quoted as saying, "I always read the book The Divine Comedy with a pen in my hand, convinced that I could write a better one."

Thompson, who doesn't see an inherent problem in applying an old template like Dante's to a new world, declined to comment on any of the quotes in particular. But he says that Dante's many insights -- which are universal and timeless -- must be handled with care, or one risks "hollowing out" terms like paradise, purgatory and inferno.

"Discarding most of Dante's universal insights or applying them haphazardly would be unfortunate," he says. "With these universal insights, it is a matter of what Dante's world would call prudence, applying them at the right time in the right way, for the right reasons."

With recent trends in Christianity envisioning divine love and mercy trumping justice, whereas traditional Christianity, through the triptych of heaven, hell and purgatory, seemed to emphasize final justice and eternal reward and punishment, Jesuit Fr. Thomas Worcester, professor of history at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts, questions what a secularized, contemporary notion of the three could mean.

"Does it mean a return to a stricter notion of justice, one in which we get what we deserve, no more and no less? Or is this too logical for a postmodern culture?" he said. "Are we left, then, with being randomly headed to some kind of heaven, hell or purgatory, for reasons beyond our knowing, and without any deity willing such a thing?"

It'd be good if secular culture could articulate more of an equivalent to divine grace and forgiveness, such as when a governor pardons convicted criminals or commutes death sentences, Worcester said. "But we need much more of that kind of grace and mercy in a U.S. society obsessed with getting what one deserves, no more and no less."

Goukassian sees things differently.

"I'm not entirely convinced of the existence of hell in the afterlife, but I definitely recognize horrific conditions in real life all over the world -- hell on earth, if you will," she said.

Curator Njami seemed to be "pretty adamant about presenting the show as a look at Dante and heaven, hell and purgatory from an intellectual standpoint, rather than a religious one," Goukassian said. "He pointed out that a lot of Africans are traditionally animists, and the whole concept of Christianity (and especially Catholicism) brings about unpleasant memories of colonialism."

Njami also emphasized, Goukassian said, that the exhibit is "only loosely based on Dante" and that "he discouraged participating artists unfamiliar with Dante from reading his epic poem, for fear of having it alter their preconceived notions of the afterlife."

"Dante seemed like more of a framework or a jumping-off point for visual discussions of the afterlife than anything else," Goukassian said.

If, indeed, artists were discouraged from actually reading the work that frames the entire exhibition, that might explain a good deal of the works. One would love to see what the show could have looked like if more of the participants had paid Dante that respect.

[Menachem Wecker is a Washington, D.C.-based reporter and co-author of the new book Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]