Global Sisters Report presents a special series on mining and extractive industries and the women religious who work to limit the damage and impact on people and the environment, through advocacy, action and policy. Pope Francis last year called for the entire mining sector to undergo "a radical paradigm change." Sisters are on the front lines to help effect that change.

______

Bishop John Yaw Afoakwah is furious. In his celebratory white cassock, he picks his way carefully through shoulder-high mounds of dirt and deep puddles to approach the man with a gun sitting in front of the bulldozer. Two Chinese engineers catch sight of a reporter with a camera, accompanying the bishop, and dash into the bush.

In front of the bulldozer is a massive pit, surrounded by three other bulldozers and a mobile crusher. Shacks housing the Ghanaian workers are perched at the edge of the pit, with a few kids darting among them.

One might expect that Ghana's illegal gold mining would be carried out hidden from public view, surreptitiously, quietly.

But behind the local Catholic clinic, in this village of a few hundred farmers, is an enormous illegal gold mine out in the open. The bishop had planned to build a nursing hospital at this site. But now the area is filled with the detritus of gold mining: destroyed agricultural land and, even more dangerous, improperly disposed cyanide and mercury that cause myriad health problems.

The skyrocketing price of gold in recent years has led to a temporary invasion here, undermining the social fabric and health of the people. An influx of foreigners, who have more cash to buy or rent earthmoving equipment, illegally remove the riches of the land, leaving a wasteland in their wake. Meanwhile, a major mining company curbed its local operations, laying off thousands now desperate for work, no matter how dangerous. In the last year, the damage from these illegal mines has grown from irritating to catastrophic, with women religious dealing with the fallout and advocating for solutions.

People living in what is now Ghana have mined for gold since ancient times, when chiefs bedecked in elaborate gold jewelry ruled over the area. Europeans arrived in the 17th century, calling the area "the Gold Coast," as they fought for control over mining and trade.

Today, the country is Africa's second-biggest gold producer, after South Africa, yet only 16 percent of Ghana's tax revenues come from gold mining, according to the Ghanaian government's Minerals Commission, which oversees the industry.

A massive growth in the value of gold over the last 15 years has also made Ghana attractive for foreign nationals. The price of gold rose from U.S. $349 an ounce in April 2001 to a high of $1,911 in August 2011. So far this year, the price has hovered between $1,100 and $1,300 per ounce.

"When gold prices went up, people started using all kind of means for small-scale mining, things like backhoes and bulldozers," explained Isaac Abraham, the senior public relations officer at the Ghanaian Minerals Commission. "This type of small-scale mining [by foreigners with heavy machinery] is fairly recent, only since 2009."

There are just eight enforcement officers to investigate illegal mining across the entire country, Abraham said. Foreigners, especially people from China, quickly caught on that profit potential soared while the chances of getting caught were low.

The illegal mining has wreaked havoc on the environment, especially the waterways, and brought a host of social and health problems to rural villages. Since commercial mining began in Obuasi in 1897, there have always been "illegal" miners, who worked without permits. Locally, these miners are called "galamsey," a variation of the phrase "gather them and sell."

Illegal and in plain sight

Bishop Afoakwah was in the middle of a homily in front of all of the village chiefs and more than 200 attendees to mark the International World Day of the Sick at the clinic in Hia, when "galamsey" workers bringing in earthmoving equipment clipped the electrical line and cut power for the entire town. There was a moment of angry silence as the machine retreated behind the clinic. The local choir hurriedly got to their feet to sing while a generator was set up.

Afterward, Afoakwah met with the village chiefs to try to determine how an illegal gold mine could be operating so brazenly on church land. Afoakwah says one of the local chiefs donated the land to the church several years ago to build the clinic and, in the future, a nursing college. He says the church holds the legal deeds to the land, and they are still fundraising to build the college.

In the meeting, the chiefs presented a complicated story of interwoven land rights, with various chiefs "protecting" land for other chiefs and, somewhere along the line, someone accepted an illegal payoff from the miners.

When Afoakwah arrived at the site after meeting with the chiefs, the Chinese miners told him that they had received a concession from a "Mr. Kumar," which Afoakwah says is impossible because the church holds the rights to the land. He has been unable to determine who Kumar is, or if he exists. AngloGold Ashanti, a multinational gold mining conglomerate that has been operating in Obuasi since 1897, controls mining concessions for most of the area.

Hia lies just outside of the AngloGold Ashanti concession, muddying the waters as to actual ownership. While the Minerals Commission maintains a database of concessions, Afoakwah has been unable to determine if it is a company or individuals operating the mine, and how they could have gotten permission.

It is illegal for foreign nationals, including the two Chinese engineers at the Hia site, to be involved in any aspect of mining. But without a clue to who owns the mine, it's also difficult to determine who owns the concession. This lack of information over land rights, common in rural areas, obstructs any attempts at oversight or enforcement.

Another contributing factor is unemployment. In November 2015, AngloGold Ashanti laid off more than 5,000 of its 7,000 workers, partly due to mechanizing its work force. It was a devastating blow for Obuasi, whose entire economy depended on the mine, and for the support industries that sprang up around the high salaries.

Within the month, the luxury shops selling flat-screen TVs and new cars closed, said Richard Ellimah, the executive director of the Center for Social Impact Studies, a Ghana-based advocacy and research group focused on the extractive industries. The city of 180,000 slid into a recession, with people struggling to put food on their tables.

So when foreign investors come to the Obuasi area, they have a willing pool of people desperate for work who have prior knowledge of mining operations. The layoffs have led to a local increase in illegal mining, exacerbated further by the increase in gold prices.

In February, Obuasi became the center of the illegal mining controversy in Ghana when AngloGold Ashanti officials went to inspect an illegal gold mine operating on their land. The miners started pelting the AngloGold Ashanti cars with rocks and, in the officials' haste to retreat, the company's public diplomacy officer, John Owusu was run over by a fleeing car and killed. The melee and resulting death was decried in the local press, but no charges were filed.

Dangers of the yellow metal

Options for employment are so few that risks from illegal mining are overlooked. "These people are oblivious of their health and the ecological issues," explained Charles Owusu Antwi, a Catholic freelance journalist who previously worked for John Owusu (no relation) as a communications officer for AngloGold Ashanti.

He said that gold mining along the riverbanks clouds the water with chemical discharge harmful to the people who drink it or use it. "We are trying to bring this to the public notice, but if you do so you do it at the peril of your life. If you are seen telling people to put a stop to the kind of things they're doing, you'll be seen as putting them out of jobs or taking the bread and butter from their table. They'll be violent to you, and you won't have it easy."

Bishop Afoakwah says this creates difficulties for church officials, who must not be seen as the ones taking jobs from needy villagers.

But Sr. Mary Owusu Frimpong, the director of health for the Diocese of Obuasi, sees firsthand the detrimental effects. "We see skin diseases and rashes from the [polluted] water," she said. Local hospitals also see horrific injuries stemming from improper use of heavy machinery. Since there is no safety oversight, Frimpong says workers have been buried alive during hasty digging.

Additionally, when the illegal miners believe that the area has been exhausted of gold, they leave without covering or filling in pits they have dug. Rain collects in these large pits, and children who play there can drown. The pools also become breeding grounds for malarial mosquitos, Frimpong explained.

Twenty sisters work in Catholic health services in Obuasi, and many of them deal with mining-related health issues.

There's also concern about long-term effects, including cancer and birth defects, from the mercury and cyanide chemicals used in small-scale mining to extract the gold from the stone. But because the mines are illegal, it's hard to track effects over time. "There's no statistics and no research [for long-term effects]," Ellimah said. "The local hospitals might have some information, but no one is really doing any research to connect the two things."

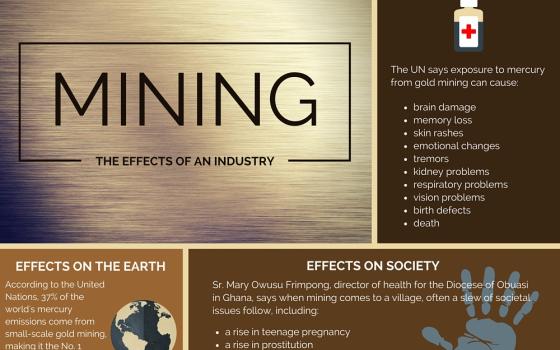

Mercury poses a major health risk through skin contact, inhalation or ingestion, and it can travel through the food chain, according to the United Nation's Industrial Development Organization, which advocates for ending its use in small-scale mining.

Mercury exposure can cause brain and neurological damage, memory loss, emotional changes, skin rashes, tremors, kidney, heart, vision and respiratory problems, fetal deformation and even death. In 2010, UNIDO reported that artisanal and small-scale gold mining, such as the illegal mine in Hia, is responsible for 37 percent of mercury emissions around the world, the largest source of air and water mercury pollution. UNIDO estimates that nearly all of this heavy metal used in the mining sector is released into the environment. While it is possible to do small-scale gold mining without mercury, it is by far the cheapest method and therefore the most widespread in illegal mines in Ghana.

When gold increases poverty

The mines also bring a host of social issues. "Because the mines bring money into an area, kids drop out of school," Frimpong said. Some are employed directly, others hang around the mines and try to collect remnants that they can resell. Health workers have also seen a rise in teenage pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, stemming from sex work. An influx of money and temporary workers into isolated, rural villages is a clear recipe for young girls to fall into prostitution, Frimpong said.

"These illegal mines are temporary," Afoakwah said. "[The miners] are only here when there's gold. They're here for three to six months and then they're laid off." By then, they have been exposed to cyanide and other toxins, he said.

The miners "take money out without developing the community," Afoakwah continued. He gestured to the area around the mine. "Here, there are no toilet facilities, people are defecating in the bush. Any money collected from the mines they should give to develop water, toilets, perhaps build a school. All the water is destroyed. People are forced to buy water. . . . They become even more impoverished, and the social effects are enormous."

Afoakwah noted that the problem stems from the way poverty forces people to operate in survival mode, concentrating on making sure there is enough food today without thinking about future generations.

"If someone says, 'I'll give you $2,000 for an acre,' it sounds huge in the mind of the poor," said the bishop. "He's ready to let go of anything, he's not educated to know that that plot of land, which has belonged to his ancestors, has supported the various generations through the years. If you come and sell traditional land for a sum of money, even if it's $10,000, what kind of investment can you make for perpetuity? . . . But because of poverty, they're ready to let go. And at the end they're more impoverished. Their land is gone, and the money runs out in two to three years."

When men can no longer support their families, the families fall apart, Frimpong said. Parents separate, children drop out of school, and everyone sinks deeper into poverty.

In rural areas, there are few opportunities besides farming. Even if the miners say they'll only need the land temporarily, the area is destroyed for generations.

Afoakwah explained just the top layer of soil in Obuasi is good for farming because it has absorbed nutrients from falling plant matter over the years. Just a meter (three feet) down, the soil is more like clay and of such poor quality that it cannot sustain a successful farm.

Dense greenery crowds in from both sides of the potholed dirt road to Hia, but here and there, the lush forest and cleared farmland is dotted with bald spots, abandoned illegal mines that have not been reclaimed by vegetation.

"When people do gold mining, the lands are doomed," said Antwi, the journalist, who has made documentaries exploring the effects of illegal mining. "They destroy it, and eventually subsistence farming grinds to a halt, because you can't use these lands for agriculture. And what comes as a result is hunger, because there won't be food for the community."

Antwi, who is the lay leader of the Obuasi diocese's Justice and Peace Commission, said he makes documentaries to help future generations understand how things spiraled out of control. "Posterity will one day blame us for the destruction of the environment," he said.

Golden opportunity

Surprisingly, both activists and government officials agree on the best way to develop Obuasi's economy and halt the rapid growth of illegal mining: legal small-scale mining. This entails redistributing concessions belonging to AngloGold Ashanti to allow locals to set up their own mines with governmental and environmental oversight.

"The key issue is the economic justice issue," said Ellimah. "If you've been in town for a few days, I don't think there's any reflection of the amount of wealth that has been taken out of the belly of the Earth. It justifies our argument — why not let our own brothers and sisters do the mining?"

"Small-scale mining is income generation," said Abraham, of the Minerals Commission, which is overseeing a redistribution of 60 percent of the AngloGold Ashanti commissions. But the process has been held up in governmental bureaucracy and is likely to take at least another year.

Even AngloGold agrees with this strategy, says Chris Nthite, head of media relations for AngloGold's corporate office in South Africa. Nthite stressed that the company voluntarily relinquished 60 percent of its concession, though some have questioned whether that land has significant gold deposits.

"It is . . . useful to draw a clear distinction between illegal mining and small-scale mining," Nthite wrote in an email. "The latter can be regulated and, when overseen effectively, can provide a livelihood for people whilst balancing the needs for tax remittances to the state and environmental stewardship. Unlike illegal mining, that allows development of a national asset (the ore body) for the benefit of all a nation's people, rather than only a narrow grouping."

Abraham also wants to create a legal path for the Chinese to invest in Ghanaian mining with local partners. Bringing the mines into a legal framework will subject them to certain environmental standards and reap local taxes for the communities where they work. He's also conscious that Ghana could benefit from foreign investment, if handled correctly.

Yet skeptics say, even if the concessions are redistributed and small-scale mining commences legally, enforcing environmental and safety regulations across rural Ghana will be a nearly impossible task, given the lack of manpower in the Minerals Commission. Abraham hopes to add another enforcement officer, but that will still mean only nine agents to patrol a country about the size of Oregon (about 240,000 square kilometers / 92,000 square miles).

Since current illegal operations rarely lead to punishment due to lax enforcement or corruption, miners have little incentive to make their business legal. Activists also warn that payoffs by miners, including foreigners, to local or even higher officials need to be stopped.

A religious responsibility

While the government has a difficult challenge, activists say religious leaders can play a unique role in Obuasi. "They should use the pulpit to sensitize the people on the dangers of illegal mining," said Ellimah, who is Pentecostal but has worked with Antwi and the Catholic church's Justice and Peace Commission on this issue. "[Religious leaders] are very influential. In Ghana, for example, whenever the Catholic Bishop Conference speaks, everybody listens, even the government. If they can be speaking about this economic justice issue, it's the only way for there to be peace in Obuasi."

Yet the spiritual message about environmental responsibility can be a tough case in the face of such poverty. "Ghanaians are very religious, Christian or Muslim, but they don't see the degradation of the environment as anything that has got to do with God," said Antwi. "Whether you destroy water bodies, so long as it gives you money, if it can put bread and butter on your table, then fine."

Ahead of a July 2015 conference devoted to mining issues, Pope Francis also demanded that the entire mining sector undergo a "radical paradigm change to improve the situation in many countries."

Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana, the president of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace who oversaw the mining conference, echoed the pope's Laudato Si' encyclical on the environment by urging everyone "to hear both the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor."

"It is morally unacceptable, politically dangerous, environmentally unsustainable and economically unjustifiable for developing countries to 'continue to fuel the development of richer countries at the cost of their own present and future,'" Turkson added, quoting from Laudato Si'.

Bishop Afoakwah also wants Ghanaians to remember their traditional religions, when ancestral forests were honored and river bodies were considered holy, with certain days when it was prohibited to disturb the waters.

"There were preventative measures, like if you gather water on a day you're not supposed to, you'll be punished," he said. "It put an element of fear into us and we conserved the environment. Now it looks like that fear of God has been taken over by materialism."

Afoakwah, who defines his responsibility as protector of the people, the land and the clinic, plans to go to court to demand remittances for the damage done to his land. But he expects the illegal miners will be long gone before the legal process concludes.

The world's hunger for gold is insatiable. Ghana is blessed with a land rich in this resource, so the mining will take place, legally or illegally.

Creating a legal path for the mines will be a considerable challenge, but activists and government officials know there is no alternative. "When [the mines] are illegal, Ghana doesn't get anything," said Abraham. "They're just ripping things out of our country."

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report and based in Israel.]

Related: Mining and extraction coalition at UN holds countries, companies accountable