Asmita Pandey, 24, worked as a waitress at a dohori sanjh restaurant in Pokhara, Nepal, in 2018. A year later, she connected with Opportunity Village Nepal, operated by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, who supported her with vocational training and financial support to set up her own business. (Pragati Shahi)

In August 2023, 17-year-old Sabita lied to her mother before getting on an overnight bus to her country’s capital. She told her mother she was taking the 15-hour bus ride from her village in southwestern Nepal to go sightseeing. She said she would be back in a week.

Instead, Sabita (whose name is changed to protect her identity) took the 400-kilometer (about 250-mile) journey to start a new job. Sabita met a friend working as a waitress in a dance bar in Thamel, Kathmandu's most famous tourist hub with a reputation for seedy late-night entertainment. The friend, whom Sabita calls Didi, which means older sister in Nepali, had promised Sabita she could get her a job with good pay at the bar.

Just for dancing on stage, Sabita, who had dropped out of school in ninth grade when there was no money left for admission fees, was told she would earn 10,000 Nepali rupees (about $75) a month, plus tips and commission. This seemed like easy money to the teenager, who loved dancing and had watched her mother struggle to feed the family with her daily wages of Rs 500 (about $3.75) at a turpentine factory in the village. Didi had also promised she could go back to school in Kathmandu, too.

"I was both excited and nervous," Sabita told Global Sisters Report. "I had heard a lot about Kathmandu and had wanted to see places like Pashupatinath and Swayambunath temples, but at the same time, I was going to this big city for the first time and did not know anyone except Didi."

Sabita soon learned she was expected to do more than dance. She started her shift at Amir Lounge and Bar at 7 p.m. Until 2 a.m., she would entertain male customers, wearing short dresses and revealing tops that would have been inappropriately immodest in her village.

Sr. Taskila Nicholas, director of Good Shepherd International Foundation Nepal, facilitates a session with youth working in Nepal's adult entertainment sectors on the International Day of the Girl Child. Oct. 11, 2021. (Pragati Shahi)

Sabita and other teenagers danced, drank and held hands with men, sitting on their laps and coaxing them to spend more at the bar. The dance bar owners sometimes forced the girls to prompt customers to drink more and pay with a large bill, and then ask to take them to an upstairs room and agree to have sex.

Sabita’s story is common in Nepal. The Alliance Against Trafficking in Women and Children in Nepal, a national-level network of nearly 40 civil society organizations working against human trafficking, estimates more than 60,000 young girls and women are engaged in the adult entertainment sector. That includes dance bars, restaurants, massage parlors, khaja ghar and dohori sanjh restaurants, of which 36% are highly vulnerable to trafficking. Khaja ghars are small-scale eateries where food and alcoholic beverages are available, and dohori sanjh restaurants cater to nightlife goers, offering live folk duet music along with dance, food and beverages.

Although it is illegal for children to work in the entertainment industry in Nepal, where abuse, harassment, and sexual exploitation are high, the majority of the workers are minor girls. The average salary of the girls joining the entertainment industry is Rs 10,000-15,000 ($75-113) per month, most of which is spent on rent, clothes and makeup products.

While the internal trafficking of young girls and women working in the entertainment industry is increasing, human trafficking is taking place in countries like India and China. Thousands of Nepalis are leaving the country to work in exploitative conditions in Gulf countries and foreign militaries in Russia and Ukraine due to a lack of jobs at home. According to data shared by Nepal’s Department of Foreign Employment, a record 775,000 Nepalis left the country to work abroad (excluding those going to India) last year alone.

Trafficking within the country is increasing, according to the 2022 national report by the National Human Rights Commission of Nepal. Most trafficked girls, however, stay inside the country and end up as domestic laborers or entertainers in dance bars, which are small and medium-size restaurants that offer dancing by young girls and women to attract male customers and mostly operate from late evening to midnight.

Nepal's Labor Act of 2017 prohibits all forms of child labor and safeguards the rights of the workers, including child workers, but the majority of the workers in the entertainment industry are unaware and incapable of utilizing the government’s benefits and security provisions. Therefore, much of the work supporting girls like Sabita has fallen to non-governmental organizations.

On Friday night, Oct. 6, Sabita and 10 other teenage girls were saved from two dance bars in a dark alleyway of Thamel, a tourist hub in Kathmandu, thanks to a coordinated anti-trafficking operation carried out by Opportunity Village Nepal (OVN), a non-governmental organization founded by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in 1998, with Nepal police and two other national organizations, Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) and Media Advocacy Group (MAG), in the adult entertainment sector.

Recounting the incident, Sabita said, "I had just finished dancing [to] three Nepali folk songs. I was resting [in] a corner when police entered the restaurant."

"I threw the cigarette in one corner and went to them when they asked about my age."

Of the 20 young girls and women employed on that day in two dance bars, 11, including Sabita, were considered minors when rescued.

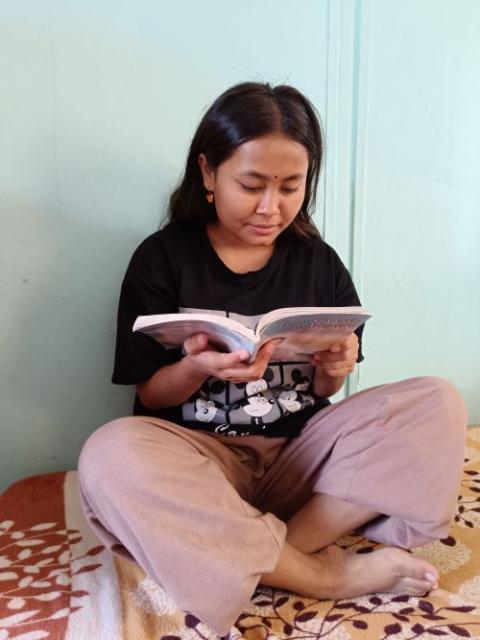

Sabita was 17 when she started dancing at a bar in Thamel, Kathmandu. She is now living at a residential shelter provided by Opportunity Village Nepal. (Pragati Shahi)

"All the girls were intoxicated when they were brought to our safe house on Friday night," Ranjana Sharma, OVN's project coordinator, who was part of the operation, told GSR. She added that, "all the girls brought to OVN's shelter that night were provided with psychosocial sessions soon upon their arrival."

Sabita is one of the two girls who have decided to remain under the protection and care of the safe house, receive further counseling and life-skill training provided by OVN, and get back on their feet. The other nine girls, Sr. Anthonia Soosaiappan, director of OVN said, were returned to their families and have agreed to get in touch to receive support from OVN to lead a life outside the entertainment industry.

Soosaiappan added that since the launch of the project against human trafficking and sexual exploitation in Nepal in 2016 in major cities, including Pokhara, Kathmandu and Bhairahawa, OVN has reached out to more than 1,000 girls and women from the entertainment industry who are at high risk of abuse and exploitation. OVN has carried out anti-trafficking operations, providing counseling and temporary safe homes for the victims, and focusing on leadership, livelihood and reintegration into society.

"Our main focus is to raise awareness of the plights of the young girls working in the entertainment sector and help them to lead a dignified life by offering them support and skill development to change their profession," Soosaiappan said.

OVN provides two safe shelters to help survivors of gender-based violence and victims of the adult entertainment industry in Kathmandu and Pokhara. The young girls and women who live at the short-term residence receive medical and educational support, life-skill development and funds to set up micro-enterprises.

Sr. Taskila Nicholas shares remarks with government and cso representatives during provincial consultation in Bhairahawa. (Pragati Shahi)

Soosaiappan added that many young girls and women fall victim to abuse, exploitation and human trafficking due to family disruptions, lack of economic support from their fathers or husbands, early marriage, forced labor, or are lured into false promises in search of jobs to support their families. With little education, and in the cases of minors, lack of legal documents proving citizenship required for other employment, working in the adult entertainment industry seems a wonderful opportunity.

Twenty-four-year-old Ashmita Pandey is one of the 300 girls who are the survivors of abuse in the entertainment sector the Sisters of the Good Shepherd support with vocational training and financial support to set up her own business. Pandey was 2 years old when her mother left, and her father, a migrant worker in India, remarried. At 14, she dropped out of school after failing to pay school fees; at 16, her stepmother forced her into a marriage with a man almost twice her age.

After enduring physical and mental abuse at the hands of her husband for a year, Pandey ran off to the nearest city, Pokhara, and took a job as a waitress at a dohori sanjh restaurant in 2018 at age 18. She was abused at the workplace by a customer and connected with OVN in 2019. She then received counseling, leadership and training as a beautician for two years. Financial support of Rs 60,000 ($451) helped her set up her own shop in Pokhara, nearly 200 kilometers (126 miles) west of the capital Kathmandu.

Pandey said, "I am thankful to OVN for their support in rebuilding my life. Now, I run a beauty parlor and earn for myself."

Sr. Taskila Nicholas, director of Good Shepherd International Foundation Nepal, who initiated the project against sexual exploitation and human trafficking in Nepal with OVN in 2018, told GSR that their main objective is to prevent sexual exploitation and human trafficking in the cities and rural areas of Pokhara and Kathmandu.

Advertisement

Cases of trafficking of children and young girls were rife soon after a devastating earthquake struck Nepal in 2015, Nicholas said, who was leading relief and rehabilitation efforts for Catholic sisters in Nepal. "We encountered several cases of abuse and exploitation of young girls and women who were desperate for work to support themselves and their families soon after the disaster," she said.

The Sisters of the Good Shepherd, who have been working in Nepal through OVN since 1998, launched the project against human trafficking and sexual exploitation of young girls and women in Pokhara in West Nepal, one of the largest cities in Nepal in 2016. Nicholas led the project as the director of OVN until 2018 and has been leading GSIF Nepal since it opened its office in 2018 in Kathmandu.

In April, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd celebrated the silver jubilee celebration of their presence in Nepal.* Nicholas said, "I had always wanted to do something for vulnerable girls and women who were at risk of human trafficking. Helping the vulnerable young women and girls to rebuild their lives is rewarding."

These days, Sabita busies herself reading story books and educational materials at the OVN shelter. Her mother was to take her home for the upcoming festival of lights, known as Tihar, which began Nov. 11. She had planned to celebrate Tihar at home, apply for a citizenship document, and get back to Kathmandu to join school. Her wish is to complete 10th grade and then a computer training course.

"I am happy to be here and grateful for the support of the sisters and staff at OVN for rebuilding my life after coming out of the dance bar," she said.

*This story has been updated to fix a typographical error in the third-from-last paragraph.