In the tiny country where a slice through the Earth connects its two greatest oceans, Maryknoll Sr. Melinda Roper and her fellow sisters have staked a claim to protect a bit of Panama's lush biodiversity — and are working to rekindle a spiritual connection to the planetary ties that bind us all.

The new eco-spiritual retreat and study program they have launched, the Web of Life, begins today, June 22, and Global Sisters Report invites readers to follow along in a series of blogs, videos and photo galleries. This union of spirituality and science will be articulated in a series of reflections by theologians and scientists in settings as diverse as bustling Panama City, an organic farm and a tropical forest.

"It's a whole historical moment that we're living in, when not only human rights are on the table but the rights of the Earth," Roper said. "What happens when the rights of the Earth come into conflict with human rights, and those rights, at least in the West, come from a very capitalistic, very individualistic, very big business philosophy and way of living?

"Many of us think we've come to a moment in history where that paradigm has got to shift, so that we in the human community can situate ourselves within the whole community of life."

Shifting that paradigm is the aim of the Web of Life program. Beginning in Panama City and then moving to the Maryknoll Pastoral Center in Santa Fe, Darién, the sisters will lead a 10-day series of explorations of the interconnections of all life. Each day will begin and end with reflection, prayer and ritual to help integrate the "experiential scientific study" along the way.

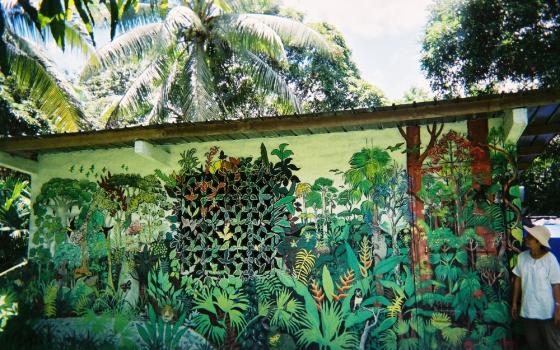

For more than two decades, the sisters have worked to set an example for a different way of life, one in harmony with their surroundings. The 100-acre forest they have preserved is a model of sustainable living, with an organic farm, solar power, rainwater catchment, a holistic health care team and a creative arts-based curriculum aimed at helping people to fall in love with sustainable ways of living on the Earth. At the same time, they've accompanied their neighbors and friends over the years in the fight to defend the natural world around them.

Those two decades of changing lives at the local level is now going global with the Web of Life.

"What we're trying to do with these 10 days is to make a real contribution to the future of the quality of life on Planet Earth," Roper said. "I think religion has a big role to play in that. … The scientific world is challenging us to new lifestyles, to new ways of living our faith, and that's very important to understand as we make political decisions and try to discover new lifestyles that don't harm the planet."

They couldn't have found a better setting to explore the theme. The Isthmus of Panama has long served as the biological bridge of the world, a critical piece in the evolutionary puzzle that is explored abundantly in the tour of the Biomuseo, Panama's much-heralded Biodiversity Museum, on June 23. Brothers Patrick and Mark Dillon, an architect and a builder who worked alongside Frank Gehry to help create it, will begin our first day by introducing us to Panama's place in the world.

Then it will be time to head southeast to the province of Darién, which despite the rapid rate of deforestation remains a hotspot of biodiversity.

Not far from the Maryknoll Pastoral Center in Santa Fe lies Matusagaratí, Panama's largest wetlands and one of the three largest in Central America. The wetlands are important breeding grounds for aquatic species of all kinds and essential feeding and watering grounds for animals that come down from the highlands: jaguars, anteaters, agoutis and coatimundis, to name a few.

However, this vast ecosystem, which La Prensa of Panama City called an "ecological jewel," is under siege on all sides by cattle ranchers and industrial agriculture businesses.

"When big companies come in, the first thing they do is drain the wetlands, eliminating biodiversity, which has many, many repercussions throughout the whole ecosystem," Roper said. "Then industrial agriculture makes intensive use of chemicals. … Then what happens when big money comes in, if the government does not have clear policies and people strong enough to implement them, the lands begin to be negotiated, and there's all kinds of corruption."

Thousands of acres have already been drained to make way for vast expanses of rice and African oil palm, and toxic pesticides and herbicides have been sprayed on the fragile ecosystem. The government designated a portion of the wetlands a biosphere reserve in January, but the illegal canals that are draining the wetlands are still in place, said journalist Ligia Arreaga in a Skype interview with GSR. Arreaga, a vocal defender of Matusagaratí, covered the issue before being forced into exile last year after she received death threats.

Web of Life topics to be explored and shared with readers include:

- The global significance of Darién and Matusagaratí and of wetlands in general. Speakers include Hermel López, the former director of environment for Darién, and Osvaldo Jordán, political scientist, biologist and executive director of the Panamanian nongovernmental organization Alianza para la Conservación y el Desarrollo (Alliance for Conservation and Development). Jordán was part of the team who carried out a socioenvironmental study of Matusagaratí for the Ministry of the Environment in 2015.

- The wetlands of Matusagaratí explored during the height of Panama's rainy season, with raincoats, galoshes and a local guide.

- Spending the day with two biologists: Ricardo Moreno, a wildcat expert and one of 14 National Geographic Emerging Explorers for 2017, founder of the nonprofit organization Yaguará, a major defender of jaguars; and tropical biologist Alicia Ibáñez, formerly of the Smithsonian and now with Panamanian Center for Research and Social Action; she is the author of the Botanical Guide to Coiba National Park.

- Sunrise birdwatching, presentation and conversations with Rosabel Miró, executive director of Panama Audubon Society, credited with helping save wetlands in Panama Bay from rampant development.

- Hikes in the forest surrounding the Pastoral Center.

- The community of Darién with anthropologist Francisco Herrera, University of Panama professor and president of the Panamanian Center for Social Action and Studies.

- A visit to the Panama Canal, called the "one of the greatest disasters in ecological history" by Patrick Dillon, who grew up in the Canal Zone, with the new perspectives gained in the days of study, conversation and reflection on the Web of Life.

"Religions and some spiritualities very prevalent today reinforce the idea the human community is the best thing that ever happened on Planet Earth and that we have the right to impose ourselves on other species and control everything for our own well-being," Roper said.

"We have to find ways of living without damaging the Earth, but we have to go way beyond that to a much more creative way of relating to the whole community of life on this planet and toward a more harmonious future," she said. "It has to go way beyond changing lifestyles. We have to create a new spirit and new values with which to relate to one another."

[Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer, editor and photographer specializing in environmental issues, indigenous rights and sustainable travel.]