Sr. Sandra López García chats with Los Monckis youth gang members during one of her team's weekly visits to their hangout in Monterrey, Mexico, in May. (Nuri Vallbona)

Sr. Sandra López García scours available parking spots on a dimly lit residential street in Monterrey, Mexico. She is trying to keep her car close to elude potential battery thieves. Accompanied by a team of lay missionaries, she and Sr. Sanjuana Morales Nájera are paying their weekly visit to "Los Monckis," a street gang of youngsters ranging in age from 7 to 26.

They approach clusters of juveniles gathered under more than a dozen pairs of tennis shoes strung over several electrical wires. Accordion music from a ranchera song drifts through the air. As the Compañía María de Nazareth sisters approach, they are greeted with waves and smiles. López García doesn't refer to the youngsters as gang members but rather as "chavos banda," or youth gangs who are not affiliated with drug cartels. These groups, she said, fight with rocks, not firearms, and although many don't sell drugs, substance abuse is common among them.

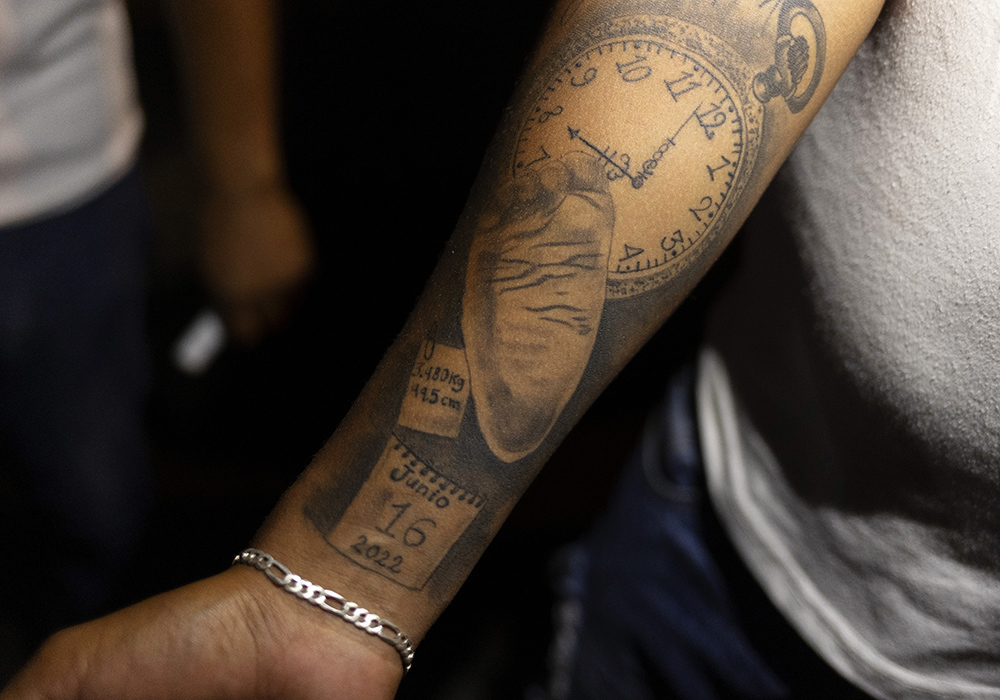

Los Monckis member Fernando Barrientos, 20, calls López García over, eagerly scrolling through his phone to show her the latest photos of his son, Liam.

"When the missionaries and the sisters come and talk to me about God's word and all that, they inspire me; they motivate me," Barrientos said, showing a tattoo marking Liam's birth. "They make me turn the page."

López García said the streets are where she finds Jesus. She and her missionary team regularly evangelize to the bandas found in Monterrey's neighborhoods. Her mission, she said, is to offer spiritual guidance and try to steer people away from drugs and violence. It's a passion she's had since she was 16 years old when she accompanied the Compañía María de Nazareth or Society of Mary of Nazareth sisters during their visits with gang members in her home state of Chiapas. When the sisters returned to Monterrey, López García went with them.

"That is when I said, 'I want to live like they live,' " López García said. "I wanted to be like the sisters."

She began her work in Monterrey as a full-time lay missionary in 2004; a year later she joined the religious community and in 2014 professed her perpetual vows. With the hopes of serving those most in need, she studied psychology while working with lay missionary groups and collaborating in the formation of novices.

"The first time I went out on the street, I was afraid because we met a guy nicknamed Rogan who had a reputation for being dangerous," López García recalled. "He was surprised that we greeted him and asked us if we thought he was bad. One of the missionaries told him that we were not afraid and assured him that God loved him. After that, Rogan burst into tears and told us that no one had ever said anything like that."

This first impact caused a radical change in López García's life. The sister felt guilty that in all the years she had run into gang members, she had never said that God loved them. In that moment, she decided to consecrate her life so guys like Rogan would not die without hearing that God loves them.

"I was called by la banda," López García said.

Sr. Sandra López García talks with Luis Alberto Pérez, 16, a member of Los Monckis, during her group's weekly visits to the chavos banda — or youth gangs — on the streets of Monterrey, Mexico. (Nuri Vallbona)

The population of Monterrey's metropolitan area is estimated at around 5.3 million people, according to 2020 census data presented by Data Mexico, a government website. However, it's impossible to guess how many gangs and bandas operate within its boundaries because some last a few years while others are passed down from one generation to the next, said Fr. José Luis Guerra Castañeda, the adviser to Raza Nueva en Cristo, which provides pastoral care to gang members. He blames family dysfunction and violence as some of the reasons the youngsters leave their homes seeking companionship and security.

"For them, the gang becomes their safe space," Guerra Castañeda said. "Some think, 'in my house they beat me and not here.' That's why they stay in the banda."

Although very few banda members take the next step to join the drug cartels, when they do, they can't get out, Guerra Castañeda said. "The way out is jail or death."

Which is why he sees the intervention of the sisters and missionaries as more than strategic. "I see it as a necessity," he said. "It's a primordial need that the guys are accompanied."

Another factor fueling the gangs is poverty. The area around St. Philomena, one of the parishes where the sisters operate, is of a low socioeconomic class, according to Fr. José Gonzalo Chaires Acosta, its pastor. This creates hardships and challenges that can at times lead to gang membership, drug addiction, unemployment or insecurity. He praised the sisters for their desire to "leave the temples and meet the brother who is suffering. The community knows their work and highly appreciates them."

Since its founding 30 years ago, the Compañía María de Nazareth charism has focused on ministering and evangelizing to youngsters, teenagers and children caught up in drug addiction, gangs or violence.

When the sisters greet banda members for the first time, they hold their hand, look them in the eye and say, "You are valuable and important," said Sr. Guillermina Burciaga Mata, the community's founder. "It doesn't matter who you are or what you have done, God loves you."

"Once they meet us, we ask permission to return to where they are," Burciaga Mata said, emphasizing the need to show respect.

The sisters' charism caught the attention of lay missionaries who, looking deep into their own lives, decided to commit themselves to that mission.

Lay missionary Josseline Montes Jiménez, right, teaches religious acclamations to members of Los Monckis, during a visit to their hangout in Monterrey, Mexico, in May. (Nuri Vallbona)

"My only child, Juan Manuel, was a chavo banda," missionary Yolanda Martínez Hernández said. "One day he was with some younger boys and another gang sought them out to provoke them. My 23-year-old son wanted to defend his friends, and the other banda member killed him with a knife."

From that moment on, she said she looked at the youth gangs with different eyes and started visiting them and preparing them to receive the sacraments.

Twice a week at around 9 p.m., the sisters and missionaries hit the streets wearing crosses and identical T-shirts with the words, "A tu lado" — "At your side" — on the back. López García encourages the team to approach as if going to meet a good friend. Although the locals know them, this does not allow them to enter all the alleys of the neighborhoods.

During a Thursday evening outing in May, the group was warned about visiting a nearby house. "There are some armed men there," Morales Nájera said. Murmurs arose and a decision was made. The visit was postponed for another night.

On the street where Los Bronx, rivals of Los Monckis, hang out, the visit was more somber. Across from the ruins of a burned-out structure, the sisters gathered in front of a memorial dedicated to two Bronx members who died recently in a motorcycle accident. Four shared one motorcycle but only two survived. López García gathered the youngsters in a semicircle and led them in prayer. As goodbyes were said, the sisters implored banda members to keep things peaceful.

"In the darkness it seems like there is no life, but we arrived in the darkness and discovered that yes, there is a lot of life," Martínez Hernández said. "We fulfilled a dream that God himself placed in our hands."

But less than an hour after the sisters' visit, missionaries got word that Los Monckis and Los Bronx had thrown rocks at each other. This did not deter the group which proceeded to a third location. López García knows that transformation can be a long process.

She remembers one particular group who got caught up with organized crime. Now when she runs into the former members, they introduce her to their wives who thank her. "Madre, he treats me very well," the women tell López García. "He's a good husband; he doesn't yell at me or hit me."

One young man joked, "Madre, forgive me, I can't quit beer but I don't do drugs."

Advertisement

Others, she said, tell her they want to send her their daughters so that they will become "monjitas," or little nuns. All these things, she said, bring her great joy. "You sow and God brings forth fruit."

During the previous decade, López García and her fellow sisters noticed that gangs had declined considerably. The cartels had arrived and killed the chavos if they refused to sell drugs. During 2012 to 2014, the sisters attended many funerals of kids and young adults aged 12 to 20. Despite this, they still combed the streets searching for banda members. In 2020, they found them in drug rehab centers.

"Without giving up going out to the streets, we decided to visit the drug rehab centers and bring our evangelization program there," López García said. "Some patients are forgotten by their families. They live in loneliness."

López García said the mission in the streets has given her a greater simplicity of faith, which allows her to meet Jesus in the least of society and in those who are excluded. God asks for her total availability to minister to the chavos in their personal processes, she added.

Around 11:15 p.m., the group piled in several cars to head home. In addition to the street visit, the sister had spent the day organizing a weekend retreat for the chavos, some who were arriving the next day. She was asked if she was tired. "Yes, it's been a long and tiring day, but full of life," she said. "It's an exhaustion that bears fruit."