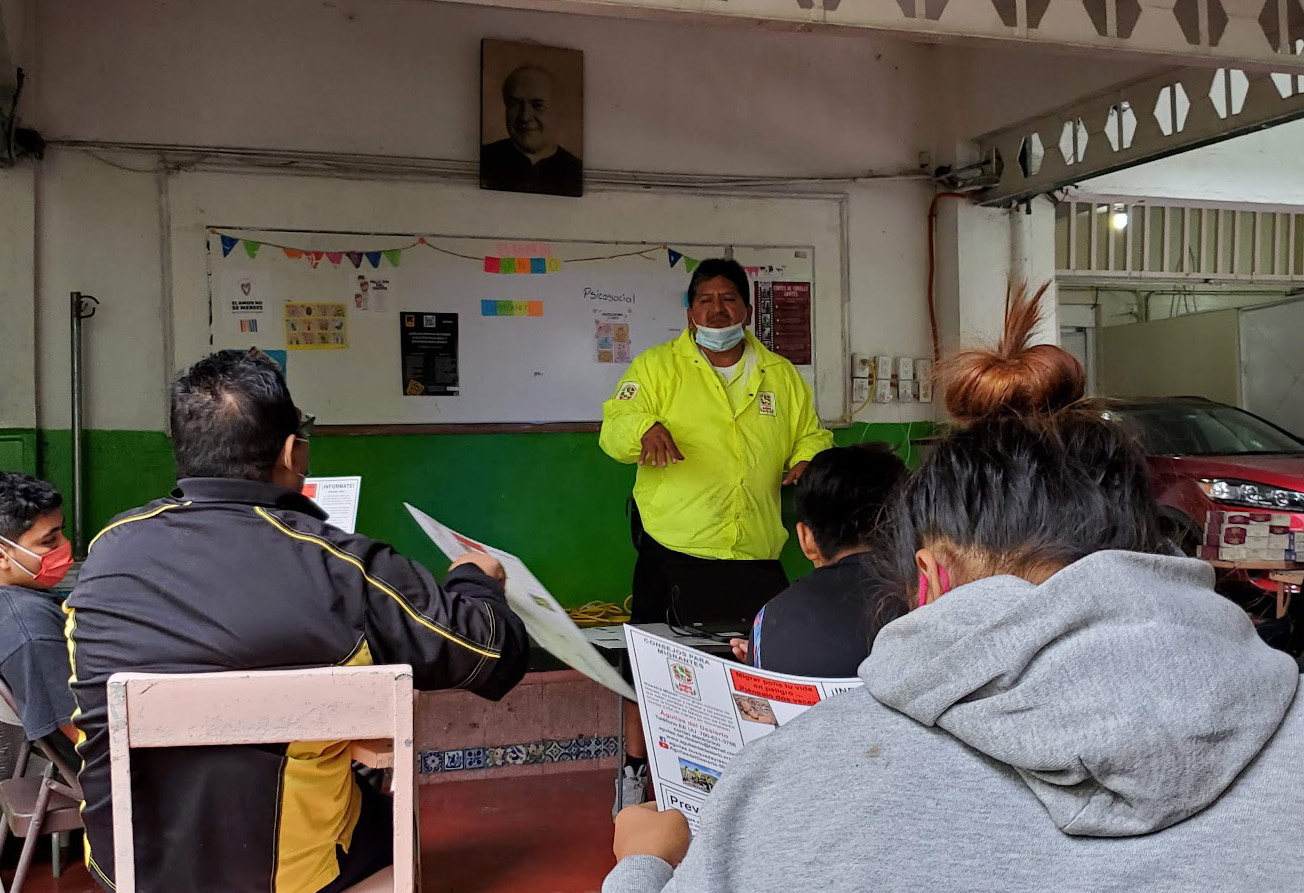

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards (right), Ely Ortiz, president of the Aguilas del Desierto (center) and Aguilas volunteer Maurizio Vitela (left) give a presentation in June on the perils of crossing the desert at a migrant shelter in Mexico City, Mexico. (Courtesy of Aguilas del Desierto)

At 18 years old, Maria (not her real name) was four months pregnant with a 1-year-old child.

She had only one concern: What would happen to her and her child if they got caught by the Border Patrol while attempting to enter the United States?

"We tried to tell her the potential dangers that come with the crossing of the border," said Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards, vice president of Aguilas del Desierto (Eagles of the Desert). "We told her it will be a difficult journey, especially traveling with her pregnancy and a young child. We asked her to piénsalo mucho," — think about it a lot.

But Maria was determined, choosing to dismiss the warning and instead continue asking about the possibility of being arrested by the Border Patrol. She was afraid that the Border Patrol would separate her and her child.

On July 14, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement took steps to ensure its agents are not unintentionally separating parents from their children at the southern border when making arrests inside the country. President Joe Biden's new directive replaces former President Donald Trump's 2017 policy, in which the resulting separation of families aimed to deter border-crossers.

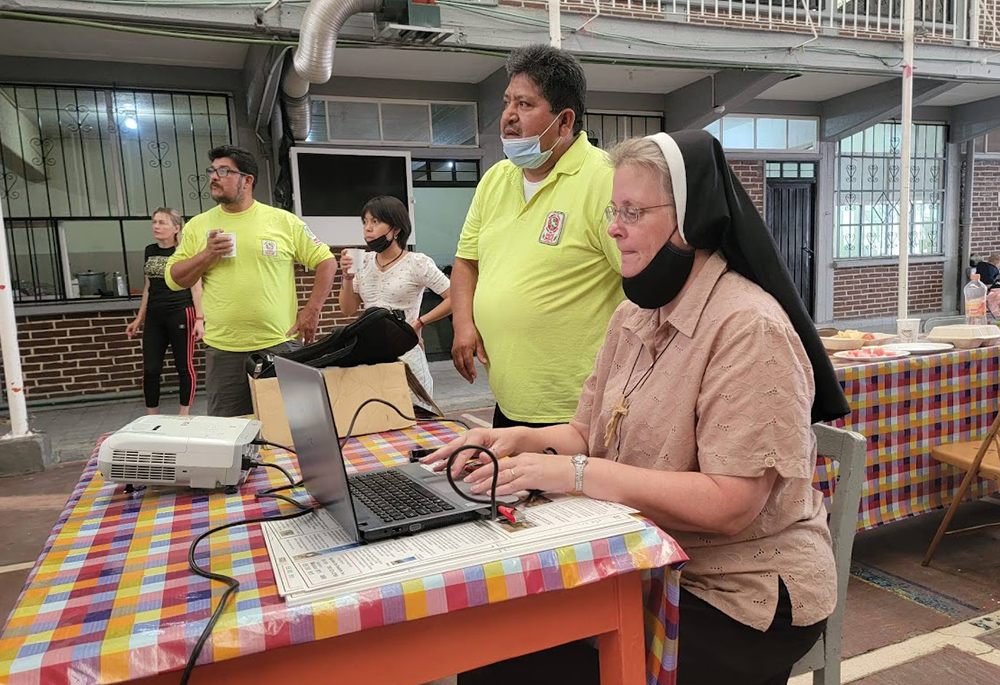

Ely Ortiz and his wife, Marisela, describe the dangers of crossing into the U.S. (Courtesy of Aguilas del Desierto)

The main mission of Aguilas del Desierto is to search for and rescue migrants who are lost, injured or deceased in the desert. They also work to save lives through a prevention and public awareness campaign, including educating migrants who are thinking of crossing the border about the real and life-threatening dangers they will encounter. In 2021, Aguilas team members recovered 22 remains and assisted in 183 rescues.

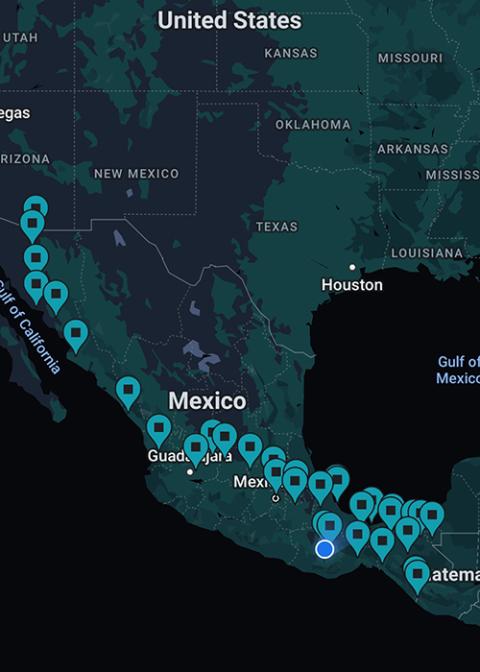

Map of the various stops on the journey, June 3-28, which included: Nogales, Santa Ana, Hermosillo, Guaymas, Empalme, Obregon, Sinaloa, Mazatlan, Tepic, Guadalajara, Tlaquepaque, León, Cardonal, Zinacantepec, Mexico City, Veracruz, Viejo, Juarez, Huimanguillo, Tabasco, Teapa, Palenque, Tenosique, San Cristobal, Tapachula, San Jorge, Ixtepec, Oaxaca, Apizaco, and Silacayoapam (Courtesy of Aguilas del Desierto)

Edwards spoke with Maria at a migrant center in Apizaco, about a three-hour drive east of Mexico City. Edwards and four other staff accompanied Ely Ortiz, president of the Aguilas del Desierto, to some 30 migrant shelters in Mexico, traveling in a van June 3-28 to promote its "Education and Awareness Campaign." They started from their base in San Diego, California, and drove through Arizona. When the Aguilas team reached Mexico, they began their campaign in Nogales, and later went to Santa Ana and Hermosillo, among other stops, completing the journey in Silacayoapam.

Edwards said if migrants were to cross the border into California, they must climb mountain after mountain. In Texas, they risk drowning in the Rio Grande. In Arizona, crossing the desert could take eight to ten days.

Looking at Maria in her T-shirt, blue jeans and tennis shoes, Edwards said, "No way would she make it with the shoes she has on."

According to the International Organization for Migration, the number of migrants who died trying to cross the border from Mexico into the U.S. from January to June 2022 was 290, and since 2014, more than 6,500 migrants have gone missing while traveling through the Americas.

Ortiz, who gave the presentation to the migrants at all the centers, said most migrants were not aware of the dangers at the border. "They could not possibly cross with the clothing and footwear they were wearing. Almost 80% have poor clothing. Many wore sandals and had no idea where they were going to try to cross the border, much less what type of terrain, nor the distance, they were going to walk."

Some centers had six to ten migrants, while some had up to 250. The team spent time answering questions, giving posters, rosaries, and information about the U.S. terrain and how best to prepare for it. With limited Spanish, Edwards passed out rosaries and gave people blessings.

Felician Sr. Maria Louise Edwards passes out a rosary to each migrant, during a presentation at a center, one of 30 migrant shelters in Mexico the team visited to promote its "Education and Awareness Campaign." (Courtesy of Aguilas del Desierto)

The further south the group traveled, the more the shelters would overflow with migrants, including families and minors traveling alone.

"I couldn't give out the rosaries fast enough; I handed out over 1,000 rosaries," Edwards said. "At one point in a huge crowd, migrants started pulling them out of my hands. Every migrant wanted to wear the rosary for protection. I remember praying that we don't find the remains of anyone wearing a rosary."

Upon receiving a rosary, Christo, a migrant from the Garifuna area, said, "Oh, you have given me a million dollars."

Ortiz, whose brother and cousin died in the desert, stressed that they need to share this prevention campaign "personally" to have a better impact and to help migrants understand that if they are not prepared, their lives are in danger.

"At each shelter, I would watch the migrants' faces as they listened about the dangers ahead," Edwards said. "They would be wary at first, then very interested — as this information was something they wanted to know — and finally, their faces dropped. Some would hold back tears. They had been through so much to reach this point in their journey, and to hear what was ahead was very discouraging for them.

"Repeatedly, I watched this happen to each group we met," she said.

Many migrants had been traveling for over a year, having been detained at one location or another. Some young boys were missing limbs from attempting to hop on trains and then falling off. Many had blisters on their feet. "Ninety percent of the people were poorly dressed, misinformed, and so full of hope," Edwards noted.

These migrants — coming from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador — are motivated to leave their country because they want a better future for their families, said Vicente Rodriguez, co-founder of Aguilas del Desierto. Rodriguez has embarked on this campaign trip four times.

Advertisement

"If you go down there, you will see plots of land they live off," he said. "They plant corn and that's all they have. You can't raise a family with that. They look at cars going by, knowing that they may never own one. If you are young and somewhat healthy, you take the risk to search for something better for your family [who've been] left behind."

Many migrants told Ortiz that that they left their countries to seek political asylum in the U.S., as their lives are in danger due to the violence.

"As we traveled the migrant trail, I saw murals painted on the shelter walls, depicting the migrant journey as a heroic valiant great adventure," Edwards said. "I struggled to process these murals, having spent the last five years recovering bodies along the border. As I had only seen the tragic end to this humanitarian crisis, it had never occurred to me that it would ever be worth the risk."

She asked her Aguilas team members — those who have come across dead bodies on their missions — whether they think the migrant's journey is still worth the risk, despite the inherent dangers.

"Everyone I spoke with said, 'Yes, it's worth the risk.' "