Dominican Sr. Diana Santleben (left) and project coordinator Farida Baremgayabo, a former refugee from Burundi, make plans for Zara's House Refugee Women and Children's Centre in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. (Tracey Edstein)

Australian Diana Santleben, of the Dominican Sisters of Eastern Australia and the Solomon Islands, has a clear memory of an incident she witnessed more than six decades ago.

"Barbara was a new girl at our school. She was Polish and she came to us with big bows in her hair and a funny dress with long pants underneath. She looked so different and I can still see a mob of kids chasing her across the playground. It was the mob mentality that fuelled the Holocaust, riots in America, apartheid – 'You're different from me and you don't belong.'

"I was with Barbara in secondary school at Santa Sabina College, Strathfield. She became part of my mob and we've been friends ever since. I learned that Barbara was her parents' seventh child and the only survivor. Her father suffered badly in a concentration camp. She was born after the war, their most precious treasure — and look how we treated her.

"I suppose that set a seed for me."

Today Santleben, 74, is founder of Zara's House Refugee Women and Children's Centre in Newcastle. Despite challenges, she has lost none of the determination and vitality that have propelled her in her Dominican life of learning and activism.

Santleben entered the Dominicans after working as an assistant primary teacher. "At Santa Sabina I had seen community in action, the friendship of the sisters and the wonderful education on offer. I wanted all that."

She loved teaching and served in several congregational schools. In 1980, she was offered a year's sabbatical at the National Pastoral Institute in Melbourne. "A whole year to do whatever I liked."

Advertisement

A change of direction saw Santleben work with young teachers in Brisbane, then return to Sydney to parish ministry.

She completed a master's thesis in early childhood religious education and then, typically, embarked on an ultimately unsuccessful campaign to convince Australia's bishops to change the system.

While working with deaf children in Sydney in 2000, she received a call from the parish secretary: "There are 12 Africans on the doorstep saying they have nowhere to live."

She said, "Boil the kettle, make some Vegemite sandwiches and I'll be down."

Santleben recalls, "I went to the presbytery [priest's home and parish office] via the real estate agent where I asked if they had a five-bedroom house to rent — today! Mum and Dad and 10 kids were Sudanese refugees and had been brought to Tasmania from Egypt by the immigration authorities in July. Imagine how cold they were! The parents had saved to bring the whole family to Sydney.

"A number of our sisters were working with refugees coming out of Villawood Immigration Detention Centre, and I became a friend of that family — the first Africans I'd ever met."

This accidental ministry involved, among other things, volunteers sourcing and storing furniture, then delivering when needed.

Zara's House volunteer Fiona Firth (left) assists Zuhal, an Afghan refugee. (Tracey Edstein)

In 2005, Santleben moved to Newcastle to care for senior sisters and establish a permaculture garden. "I came to Newcastle to live peacefully and quietly; you leave your boats behind."

God had other plans.

Santleben soon wondered what happens to refugees in the Hunter region. She learned that Josephite Sr. Betty Brown was the go-to person. "I rang her and said, 'I'm a Dominican — I've got a trailer — can you use me?' "

Brown and Santleben became friends, sharing a commitment to offering care and advocacy to refugee families. Brown had been ministering to refugees in Newcastle but without a base. Together, they established Penola House in a defunct police station. Penola was the South Australian town where St. Mary of the Cross MacKillop founded the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart in 1866.

The Dominican and the Josephite worked together from 2008 until 2012, when a successful Indigenous land claim made it impossible to remain in Penola House.

Brown has retired but Santleben remains actively involved. She has learned hard lessons about the not-always-fruitful interaction of government agency and not-for-profit organization, congregation and diocese, bishops and lay groups. She saw a new way forward that would hopefully marshal the goodwill of Novocastrians (natives of Newcastle) who wished to support the refugees in their midst.

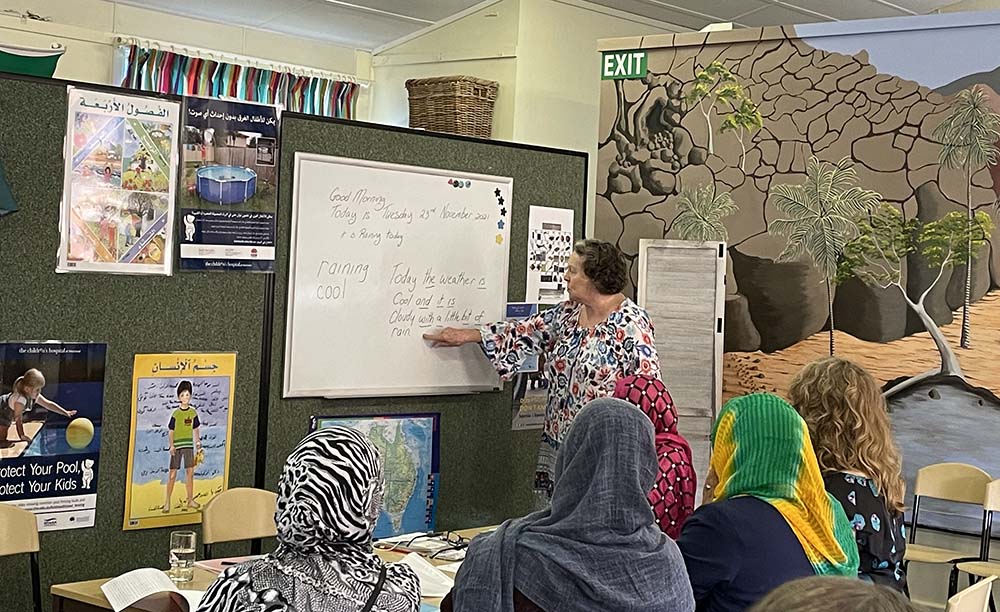

Volunteer Monica Byrnes leads a language class for women refugees at Zara's House. (Tracey Edstein)

With a group of generous supporters, Santleben established Zara's House Refugee Women and Children's Centre in 2016. Here she offers a mother language literacy program, leading hopefully to English literacy for women and children; early childhood education; classes to assist refugees preparing for the citizenship test; classes in small business development, microfinance facilitation and financial counseling.

Volunteer Monica Byrnes says, "I had long wanted to help refugee women with their English, so I came here. I do what I can to help them converse. We've had great times talking about the clothing they're wearing and had funny fashion parades and we all enjoy a laugh."

Why Zara's House?

The center has served two Zaras — an Afghan woman and a little girl — so the name captures the scope of the work. Also, Christians, Jews and Muslims are the children of the book who look on Abraham and Zara (Sarah) as their parents in faith.

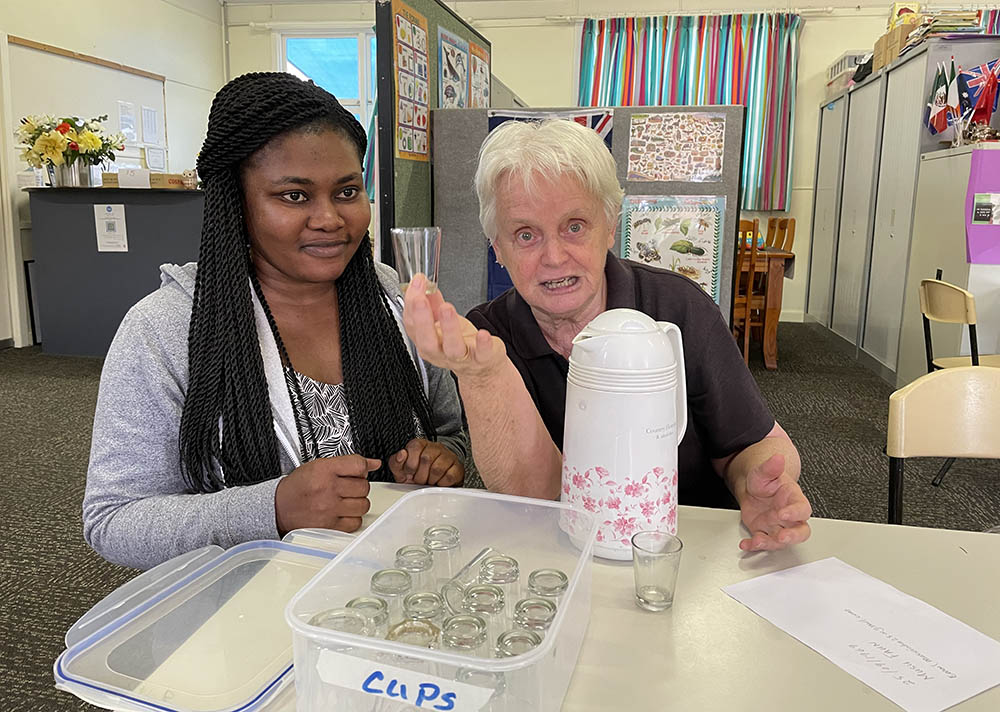

Recently, Santleben decided to step back from being projects coordinator. ("Dominicans are itinerants. ... We don't have to be the people who do it all," she says.)

Dominican Sr. Diana Santleben, founder of Zara's House for refugees in Newcastle, New South Wales, meets with a new financial coordinator, Mary Amponsah. (Tracey Edstein)

She needs to concentrate on the greatest work of Zara's House: advocacy. "The refugee network here is strong, and refugees mostly look after each other, but we're struggling to save the lives of people who become asylum seekers. The system's cruelty is breathtaking."

She shares what she regards as Zara's House's greatest success story.

Nurse-midwife Helena, who asked that she not be identified fully, came from Liberia with four daughters when she was about 50 to gain a master's in public health at the University of Newcastle, Santleben recounts.

"We met the family at a local church — Helena was just another international student. When she was preparing to return to Liberia, she received a letter saying her grandmother had died. Her grandmother was the chief zoe [female cleric and tribal leader] who oversees female genital mutilation. Most of our women here have had that done to them. There's no medical reason, it's tradition. It removes any enjoyment of sex, and makes the woman compliant with her husband.

"The letter indicated that Helena would succeed her grandmother. 'You're the best person to do this — a nurse and a midwife. ... You'll raise the standard and fewer girls will die.'

"We didn't hesitate in trying to get a protection visa for the mother and daughters. God's grace led to a lawyer taking on what she knew to be a very difficult case with little likelihood of success. We interviewed every Liberian man we could find and asked, 'If you had a wife or a female relative who didn't want her daughters mutilated, would you insist?' Every one said yes. Then we asked every Liberian woman we could find — 'Would you want this done to your daughters?' All of them said no."

Volunteer Marie Tiller leads a language class for women refugees at Zara's House. (Tracey Edstein)

A psychological profile showed that Helena had profound post-traumatic stress disorder because she had seen female genital mutilation performed many times. She had only escaped undergoing it herself because she'd been relinquished by her father — "another story," Santleben concludes.

Previously, the government had refused protection to keep her from having to return home because it claimed that the ECOWAS passport common to several West African countries meant that women could safely return to another country. Lawyers at the University of Newcastle demonstrated that this was not so, because women would eventually be required to return to their own country.

Santleben recalls, "The government had no excuse not to give Helena a protection visa and her application was accepted on the first round — an unprecedented outcome. We're so proud of this!"

Helena and her daughters have been able to stay in Newcastle and remain connected to Zara's House.

In November 2021, Farida Baremgayabo (rear) took over as Zara's House project coordinator from Dominican Sr. Diana Santleben. Here, they work together on a new path for the refugee house in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. (Tracey Edstein)

The new projects coordinator, Farida Baremgayabo, has in the past been supported by Santleben and is more than ready to pay it forward. Her enthusiasm and her work ethic echo Santleben's and she has raised her seven children (four born in Newcastle) to respond to the needs of those around them.

Baremgayabo, a nurse, was living with her husband, Salim, in Burundi, East Africa. As their family grew, the couple became increasingly concerned about the political situation. The elected president had been killed and the conflict between Hutu and Tutsi tribes showed no signs of abating.

The family left Burundi for the Democratic Republic of Congo, then Tanzania, then South Africa, but did not find the peace they sought. The idea of leaving Africa entirely was appealing, so they applied to go to Australia as refugees. The process was long — "a little bit stressful," Baremgayabo says — and meanwhile she became pregnant with her fourth child.

When the green light to travel to Australia was given, it involved leaving workplaces, extended family, a home and most of their possessions, all in a matter of days.

On arrival in Newcastle, Baremgayabo was told by her case manager that "Sister Diana and Sister Betty will look after you." They did — even to taking her home from the hospital after the birth of her fourth child. Baremgayabo says, "The sisters became grandmothers to little Aaliyah!"

Baremgayabo is a gift to Newcastle. "I wanted every day to do something for the community." One day, she drove past Zara's House to see Santleben laying a path, alone. She said to her son, who was with her, that they needed to help the sister. On another occasion when Baremgayabo was keen to become involved with a project, one of the children said, "Mum, we know you like to help the community — we will look after our siblings."

The resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2021 has led to the arrival of Afghan families, joining those who came some years ago. Zuhal, a young woman from Afghanistan, relays, with Santleben's encouragement, that her brother, Faisal, had been an interpreter with the Australian military and was offered the opportunity to come here with his family. "Faisal brought Mum and his three sisters to Newcastle and now we are all married and have our own families.

Zuhal, an Afghan refugee, with sons Sabhan (left) and C.J., takes advantage of the programs at Zara's House in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. (Tracey Edstein)

"I'm very happy here because here is safety, and Afghanistan is now very dangerous. ... So many people have died."

Volunteer Fiona Firth, a midwife who has helped pregnant refugees, has been assisting Zuhal with her English while Zuhal's little sons, C.J. and Sabhan, are cared for in the children's room. Firth says, "The women like being with other women. It's about citizenship preparation but also about being social."

Santleben recognizes a strong thread of racism in Australia's history, including the recent "exploitation of irrational fears around desperate people legally escaping tyranny in boats."

"However, I believe the tide is turning when I reflect on the daily calls from strangers asking to become volunteers, offering donations and asking what can they do to welcome refugees to Newcastle."

Did that little girl with the big bows in her hair and a funny dress understand the impact she might have in the end?