Sr. Sylvia Ndubuaku draws a blood sample from a patient for a free test at the Family Life Centre in Mbribit Itam in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria, in 2020. (Kelechukwu Iruoma)

Five years ago, Itam Ngoyo (not her real name), a native of Oron, a small community in southern Nigeria, started to defecate and urinate unconsciously and uncontrollably. Ngoyo, who lives 55 kilometers from Uyo, the capital of Akwa Ibom state in the country's oil-rich region, thought the condition was normal until it persisted. She was worried but due to the stigma, she could not seek medical help.

Subsequently, she started feeling sick and losing weight. Then, she concluded it was an abnormal condition that could kill her. Ngoyo, who hails from a community where there is no access to quality health care, visited a few clinics as her health continued to deteriorate. The tall, dark woman visited prophets, who failed to heal her, and herbalists, who gave her medicinal concoctions to drink.

Each year, 50,000 to 100,000 women worldwide develop obstetric fistula, an abnormal connection between the vagina and rectum or bladder, according to the World Health Organization; the organization reported that it "may develop after prolonged and obstructed labor and lead to continuous urinary and fecal incontinence." The health organization also said fistula can be an outgrowth of the common African practices of child marriage and Female Genital Mutilation.

As reported by P.M. News, about 12,000 Nigerian women annually are estimated to develop vesicovaginal fistula, the kind that connects the vagina and bladder; of this, only 5,000 cases are treated, according to the National Obstetric Fistula Centre in Katsina. No official data show the number of women who have died as a result of fistula.

Many women, including Ngoyo, suffered with fistula for years due to a lack of fistula care centers, especially in rural areas. This has been identified as a major reason many fistula cases are untreated.

With no improvement to her health condition, Ngoyo was referred by relatives to the Family Life Centre, a fistula and maternal birth injury hospital run by the Medical Missionaries of Mary, a congregation of Catholic sisters dedicated to providing healthcare to the less privileged.

At the center, Ngoyo was diagnosed with fistula. "I was told I needed an operation. I was given drugs for two weeks to stabilize my system before I could be operated on," she recounted. "I later returned for the operation and it was successful."

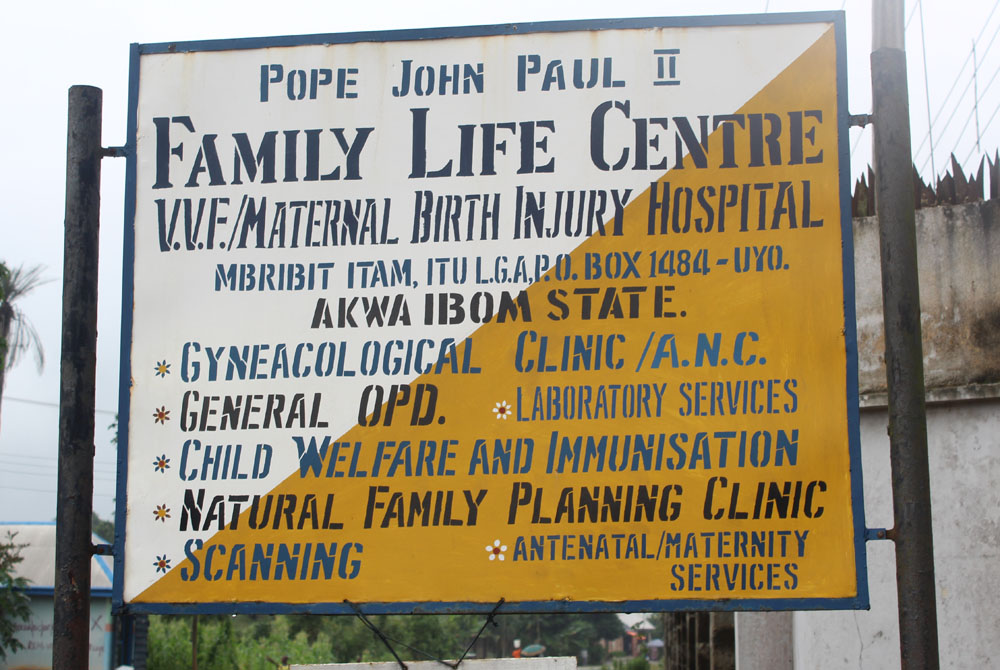

The Family Life Centre, run by Medical Missionaries of Mary in Uyo, Nigeria, offers free surgeries to women with fistula and treats other health issues. (Kelechukwu Iruoma)

Repairing damaged organs for free

The center operates on about 200 fistula cases annually. "We repair damaged bladders, rectums and the female reproductive organs," said Sr. Sylvia Ndubuaku, the matron of the center. "The goal of sisters of the Medical Missionaries of Mary is to work where the needs are the greatest. We see traumatized women doing as if the world has collapsed on them. Many of them have lost their dignity."

The late Sr. Ann Ward from Ireland, who worked in Uyo in southern Nigeria, founded the center. She discovered that many women had vesicovaginal fistula and rectovaginal fistula and were not being treated. As a gynecologist, she established the center in 1990 to treat patients for free. After her retirement in 2006, the sisters at Itam, where the center is located in Uyo, continued the work and they have been helping hundreds of women every year.

Three other sisters, Margaret Mary Oko-oboh, Jacinta Lumenze and Amushe Ogbuokili, assist Ndubuaku in the day-to-day running of the center.

Since less than half of women with fistula, who mostly live in rural areas, are treated, the sisters and auxiliary staff engage in community outreach by visiting villages to scout women with the condition. They also make announcements about their services on local radio and television stations as well as social media.

"We also train women on how to identify and prevent vesicovaginal fistula," Ndubuaku said. Four times every year, they treat and perform surgeries on women with the condition. For several years, the center has not had any resident surgeon.

Srs. Sylvia Ndubuaku (from left), Amushe Ogbuokili and Margaret Mary Oko-oboh of the Medical Missionaries of Mary run the Family Life Centre in Uyo, Nigeria. (Kelechukwu Iruoma)

To perform the operations, the center hired Sunday Adeoye, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and also the recent chief medical director of the National Obstetric Fistula Centre, a hospital in Abakaliki, southeast Nigeria. Dr. Sunday Lengmang, a fistula surgeon at the Evangel Vesico-Vaginal Fistula Center* in northern Nigeria, also does surgeries at the center.

The surgeons reconstruct the urinary, bladder and rectal tracts to stem the free flow of waste products in the system. The doctors are paid through fundraising efforts by the Medical Missionaries of Mary and by funding from the United Nations Population Fund.

To keep fistula from developing, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said early detection of a vaginal tract injury and operating on it as soon as possible can prevent the formation of the condition.

Cost of transportation to and from the center was identified as a major barrier to fistula treatment. The sisters bought a 16-seat bus to convey patients to the center for treatment.

"Not all hospitals give vesicovaginal fistula patients attention. The fact that sisters run the center shows that we run it with special care, which makes it unique. We focus on treating human beings and not making money," said Ndubuaku.

Sr. Sylvia Ndubuaku pushes a fistula patient by wheelchair at the center. (Kelechukwu Iruoma)

After the surgery, she says, the sisters adopt the social reintegration method to return patients to their communities. This is to help them fight stigma and overcome social and socioeconomic challenges.

Patients spend months at the rehabilitation center to fully recover. The sisters teach them some skills, such as hairdressing, tailoring and baking. At the end of the training, the sisters equip them to return to their communities and start their businesses.

"Some of them lost their businesses due to the illness. That is why we teach them some skills and empower them materially and financially so that they can start some businesses when they return home," Ndubuaku said.

When Global Sisters Report met a woman who calls herself Happiness Asuquo, she was recuperating after surgery for fistula two years earlier. Her tone and mood changed as she narrated her near-death ordeal. Like Ngoyo, she was defecating and urinating uncontrollably and not privy to what was wrong with her until she was referred to the center.

"I could not walk. I was always crying. I begged God. I thought I would die," she said tearfully. Asuquo had surgery and treatment free of charge at the center. Ngoyo and Asuquo are now being trained to make wigs and style hair. The sisters also feed them throughout the rehabilitation period.

Sr. Sylvia Ndubuaku assists fistula survivors who are being trained in hairdressing as part of their rehabilitation at the Family Life Centre in Uyo, Nigeria. (Kelechukwu Iruoma)

With support from the U.N. Population Fund, which trains their staff, and from the Fistula Foundation that pays for supplies and provides equipment for the surgeries, the sisters have continued to treat fistula for free.

"The center and hospital are staffed by the mission and the government. The government helps us with some staff salary while the mission pays the rest with help from ExxonMobil Nigeria, an oil-producing company," says Ndubuaku.

In 2013, the sisters introduced other treatments to increase access to health care with a view to reducing maternal mortality, tuberculosis, HIV and diabetes mellitus. Nigeria's health indicators are poor. It has the world's highest rate of HIV and AIDS-related deaths as well as high rates of maternal and infant mortality.

"We treat every type of ill health, including running free tests. We do antenatal and we care for children and mothers. The thing is that vesicovaginal fistula [surgery] is the only treatment we render free, every other case is paid for," Ndubuaku said.

To reach more women with fistula, the sisters run a mobile clinic, which also covers immunizations, school health, general health and treatment of diseases.

"The general treatment of the mobile clinic is free. We go to churches and rural communities to talk about health. We observed that people are having diabetes mellitus and hypertension, and they are dying. We decided to talk about the prevention of these diseases."

Oko-oboh, who has been in the sisterhood for 43 years, is a trained nurse and HIV counselor while Ogbuokili specializes in administration and finance.

"I feel very happy doing this work," Ndubuaku said. "It is challenging but I feel fulfilled when I can alleviate the pain from others because that is what God called me to do. Being a sister gives me that freedom. If I were married, I would always pay attention to my family, but as a sister, I care for all and don't neglect anyone."

Asuquo is now walking perfectly and Ngoyo has regained weight.

"Now, I feel much better," Ngoyo said as she spun around, smiling. "If you have vesicovaginal fistula, come here and it will be solved.''

[Kelechukwu Iruoma is a freelance journalist based in Nigeria.]

*This story has been updated to correct that Adeoye was recently the director, and to correct the name of Lengmang's facility.

Advertisement