Scattered grain sits inside a warehouse damaged by Russian attacks in Cherkaska Lozova, outskirts of Kharkiv, eastern Ukraine, May 28. (AP photo/Bernat Armangue, File)

In the shadow of global forces, Sr. Monica Moeketsi sees, hears and feels tensions all around her.

Inflation is putting pressure on all aspects of life in her small southern African nation of Lesotho. What cost 18 loti ($1) in February now costs three times as much. Food, soap, medical supplies — everything is affected.

And that, Moeketsi said, has led to a spike in fighting, stealing, robberies, and even killings. Families struggle to hold on to jobs. Violent incidences are up among students at their schools.

"It's very serious, these tensions that families are experiencing," said Moeketsi, a member of the Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (Good Shepherd Sisters of Quebec) and secretary-general of the Catholic Leadership Conference of Consecrated Life in Lesotho. "I am seriously worried."

Sr. Mary Lilly Driciru sees similar problems in Uganda: high inflation affects food and fuel prices — which in some cases have doubled in just the last few weeks — and unpredictable weather varies between drought and flooding, all at a moment when Ugandans were hoping for better times after two years of COVID-19-related lockdowns and economic downturns.

"It's hope against hope," said Driciru, who said she hears stories of despondency and stress and of people working day and night to try to stay ahead in poor areas of Uganda's capital of Kampala.

Sr. Mary Lilly Driciru of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church hosts her weekly radio show at Radio Maria Uganda on April 30. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

"Many people live on the bare minimum, and others are literally going hungry," Driciru, a member of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Mother of the Church, told Global Sisters Report.

Driciru and Moeketsi, like humanitarian officials who also talked to GSR, see a perfect storm that began with the Feb. 24 start of the war in Ukraine, which rattled international economic markets and disrupted grain exports to many parts of the world, leading to an increase in global hunger that will not be easily solved in the short term.

That has particular poignancy as the global community marks World Food Day on Oct. 16.

Some things have improved in the last eight months. As part of a July grain agreement, Russia has eased its blockage of grain shipments from Ukrainian ports, which lowered global food prices. In September, United Nations trade chief Rebeca Grynspan said the drop had eased some for "1.6 billion people in the world that have been facing a cost-of-living rise, especially because of the increase in food prices."

But Grynspan acknowledged that, as UN News reported in September, the price drops are not yet reflected in local domestic markets like the ones in Lesotho and Uganda. As a result, developing countries are still struggling with high food prices, inflation, and currency devaluations, the news agency reported.

A Catholic Relief Services distribution in Nakivale Refugee Settlement in Uganda. Refugees received a startup kit including shelter tarpaulin, poles, ropes, blankets, a net, mats, a solar lamp and a kitchen set. (Courtesy of Catholic Relief Services/Jjumba Martin)

Despite the resumption of grain exports from Ukraine, the world is "heading toward the tightest grain inventories in years," the Reuters news agency reported in September. One problem is that drought and poor weather "in key agricultural regions from the United States to France and China is shrinking grain harvests and cutting inventories, heightening the risk of famine in some of the world's poorest nations."

Still, the war in Ukraine has remained the most visible symbol of the challenges for the global food supply.

Its impact "rests heavy on the continent of Africa," said Driciru, a journalist and communicator by training who serves as communications and Africa faith and justice coordinator for the Association of Religious in Uganda.

While the initial grain blockage didn't directly affect countries like Uganda, it hurt the global economy in other ways, with a reduction in trade that wreaked havoc on foreign exchange, she said.

"Given the fact that Africa is still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic with its negative effects of unemployment and declining business trends, the Russian war on Ukraine is yet a new blow on the African economy," she wrote recently in a reflection she shared with GSR.

"The conflict is poised to drive up already soaring food prices across the globe. Ukraine and Russia, which is under heavy economic sanctions for invading its neighbor, account for one-third of global grain exports," Driciru wrote. "The economic challenges that are bound to affect the world also affect Africa as part of the global community."

A Somali woman fills a container with water Sept. 20 at a camp for displaced people on the outskirts of Dollow, Somalia. Somalia has long known droughts, but the climate shocks are now coming more frequently, leaving less room to recover and prepare for the next. (AP photo/Jerome Delay)

Similar challenges in the Americas

Other parts of the world face similar dynamics, including the Americas.

Lola Castro, the World Food Program's regional representative for Latin America and the Caribbean, said in an interview with GSR that at the beginning of the year, there were about 8.3 million people in the region who were "severely food insecure," lacking access to a regular source of food.

Those numbers have increased by about 15% since the beginning of the year, Castro said. In all, 74 million people face moderate to severe food insecurity, which corresponds to about 40% of the population of the 11 countries and territories considered, said World Food Program spokesperson Norha Restrepo.

The inflation numbers in some countries are telling, Castro added: Colombia had 2% food inflation in 2019 and about 25% this year, she said.

"All the countries where we work also import more than they produce, or at least half and half, but we have countries that import 80% of what they consume," she said. "And obviously, although we may not in Latin America and the Caribbean be buying directly from the Black Sea, we buy indirectly, and also we buy fertilizers very much directly. So we are seeing an overall impact on the global food prices."

Advertisement

And while food prices have decreased in recent weeks, they have still not returned to previous levels, and many people still cannot buy the food they need, Castro said.

The challenges of global inflation are just one factor in the current economic hardships in the region, she said.

"COVID-19 brought a huge economic downturn and increase of poverty and loss of middle-class and development gains" that had been made over nearly three decades, Castro said. "While we should not forget the poorest of the poor that are the ones suffering the most, COVID brought the middle class of Latin America down to almost poverty levels in not having a cushion."

Another troubling dynamic: climate change. In the last month, two big hurricanes — Fiona and Ian — hit the Dominican Republic and Cuba, respectively. Though Ian gained strength over Florida, its effects on Cuba were considerable, Castro said.

"What happened in Cuba, in the west of Cuba, is a huge loss, also, of production that they had in tobacco, bananas, yuca, and other products," she said. "The climate crisis continues being an issue and a problem for food security in the region."

A woman passes Ukrainian servicemen patrolling an area Sept. 14 in Izium. (CNS/Reuters/Gleb Garanich)

Add the war in Ukraine, and "it's compounding crises, one after another, and the resilience of the people is eroded, basically. They cannot cope anymore. I mean, you are a family, a woman farming in the dry corridor of Honduras, and you got the [2020] Eta hurricane," she said. "On top, you got COVID-19, where you couldn't plant or couldn't move your harvest. And then you get that everything you buy is double in price."

Similar pressures exist in the United States, said Adrian Dominican Sr. Donna Markham, president of Catholic Charities USA.

Economically poor people in the United States right now are as "vulnerable as people in any part of the world," Markham said in an interview with GSR. The result, she said, is that Catholic Charities' services like food pantries are being pushed to their limits, and donor fatigue is rising.

"These are difficult, challenging times," Markham said.

Adding to the current concerns in the United States are the continued trauma and grief from the pandemic, serious and often ugly political divisions, and a housing shortage that has caused home prices to skyrocket.

Such problems affect both urban and rural areas in the United States, Markham said.

"There are great needs everywhere," she said.

People receive food donations July 13 from a food pantry outside a church in the Bronx borough of New York City. (CNS/Reuters/Shannon Stapleton)

Sisters and aid groups do their best with what they have

Unraveling all of those great needs globally could take at least two to three years, said Shaun Ferris, senior technical adviser for agriculture, livelihoods and markets for the Baltimore-based humanitarian organization Catholic Relief Services.

Since there is less foreign exchange in the world since the start of the war in Ukraine, Ferris said governments are more constrained about what they can do to counter some of the challenges.

That means a larger burden on humanitarian groups to fill in gaps.

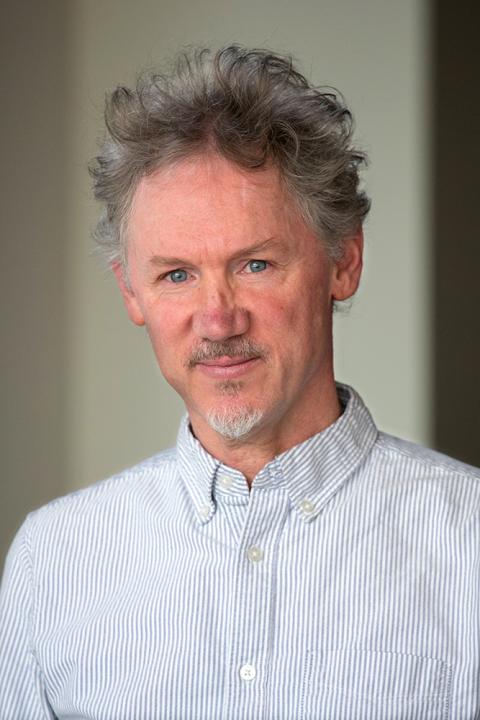

Shaun Ferris (Courtesy of Catholic Relief Services)

"The situation is very serious, and there's a need [to respond] for those in crisis," said Ferris, who is based in Nairobi, Kenya. This includes long-term assistance to farmers for the next five to 10 years and even beyond, given the challenges of drought and climate change in much of the world.

In East Africa, the lack of rain is "becoming a nail-biter every year," he said. "The effects of climate change are becoming more severe."

Action to counter climate change in affected areas is still possible to increase agricultural production in parts of Africa, Ferris said. "Africa can go a long way to feeding itself, but it needs support."

As it is now, East Africa is on the brink of a major food security crisis because of the effects of climate change, the decrease in markets because of COVID-related challenges, the war in Ukraine, and the spike in food prices, Ferris said.

"All are having a ripple effect, with multiple factors happening at once," he said.

One outcome: an overall loss of confidence, he said.

"When millions of people lose hope for the future, that's not good for any society," he said.

Moeketsi in Lesotho said religious congregations can feel frustrated in an uncertain environment in which political leaders perceived as corrupt are not doing enough to meet the current crises.

Her congregation is doing its best, though, to provide food when needed.

In Uganda, Driciru sees similar challenges and problems. She said government corruption undercuts any real hope of substantive, meaningful change.

"Taking advantage of the poor is part of the order of the day," she said of the present political climate.

The eight congregations that run schools in Lesotho are keeping the focus on helping students envision a better future — part of efforts, Moeketsi said, for the congregations "to go the extra mile."

Driciru said that is important during a period of global and local tension and uncertainty.

"It's time to be mindful of each other," she said, "just like Jesus responded to needs in his time."