Salvatorian Sr. Cyrel Peralta is the book reading program and advocacy coordinator for the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program in Metro Manila, the Philippines. The program's mobile library for book reading on the Gospel and children's rights has toured communities regularly since it began in 2004. (Courtesy of Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children)

"Baliw na bata" (crazy child) was how a girl was known in the Novaliches Diocese in Quezon City until Sr. Mary Adeline Abamo of the Sisters of the Divine Savior came there in 2001. The girl, who was not yet in her teens, just kept murmuring words.

Because of Abamo's presence and her pioneering work in the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program of the Sisters of the Divine Savior, a neighbor of the girl in the Parokya ng Mabuting Pastol (Parish of the Good Shepherd) broke her silence and reported the cause of the girl's mental state.

When Abamo looked into the matter, it turned out that the girl had been repeatedly sexually abused by a man in the village. "Because the sexual abuses had not been ventilated, the girl became mentally disturbed," Abamo said, citing her assessment.

She was not able to seek help from the legal network because the abuser went into hiding. However, with consent from the mother, Abamo managed the case and counseled the mother and child.

In the first decade that she was involved in the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program in the archdiocese and its parishes and basic ecclesial communities, Abamo handled 100 cases.

Salvatorian Sr. Mary Adeline Abamo poses next to a portrait of the founder of the Society of the Divine Savior, Blessed Francis Mary of the Cross Jordan. (Tonette Orejas)

The "rampant abuse of children, who were most vulnerable," prompted the Salvatorian sisters to initiate the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children as a "major social apostolate," Abamo explained. The mission officially launched on Aug. 15, 2001, after three years of discernment and consultations. Abamo is now the outgoing regional superior and was interviewed with Salvatorian Sr. Ruth Baguinon in late February.

"We wanted to provide a holistic response to whatever needs of children—being poor, being wounded. We thought the treatment to be within the circles of family, community and parish," recalled Abamo, 60, who has devoted 18 years to the program.

"Our options were to start a program that is parish-based, center- or community-based, or centered on play therapy," she added. The Salvatorian sisters chose a parish-based structure because it could cultivate a wider network and share or pool resources.

The program has become so successful that it is being used as a model in parishes throughout the Philippines. As of 2021, "all 73 parishes spread across 12 vicariates [in the Novaliches Diocese] are involved in the program and are in varying levels of becoming more child-friendly parishes," the congregation wrote in the book Care and Protection of Children in the Parish Community: Two Decades of SPCC Experience.

Moreover, child advocates, former victims and even entire families who serve as advocates vouch for the difference it has made in the lives of children, teens and adults.

From left: Julie, Flordeliza, Joseph and Julius Genetiano are advocates with the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program. (Tonette Orejas)

Julie Genetiano was an advocate in Grade 4 in 2013 when she joined a "formation," which is part of the parish program structure. The next year, Julie saved a friend who was battered by her father.

This case inspired Julie's mother, Flordeliza, to become an advocate, and so did her father, Joseph, a lay minister, and younger brother, Julius. The family of four continues to involve itself whenever an incident of child abuse is confirmed and works with barangay (village organization) organizations and state social workers to protect minors. Julius, 14, is more involved in the mobile library and book reading.

"Our being advocates have strengthened our family bond," said Joseph, who fixes tricycles for a living.

The success of the program

The Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children is faith-based as expressed in social teachings in the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines in 1991 and the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines pastoral letter in 1998, "Welcoming Them for My Sake," on the exploitation of Filipino children. These were taught to 2,584 children's rights advocates in training and congresses.

The protection of children, Abamo noted, gained more importance because Pope Francis instituted the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors in March 2014 and held what was considered a high-level summit on the protection of children in 2019.

The Salvatorian sisters expanded the pastoral care for children to two more parishes in the Novaliches Diocese in the program's 15th year in 2014. Then-Bishop Antonio Tobias formed the Pastoral Care for Children and Vulnerable Adults program, operating under the Diocesan Commission on Social Action.

Parokya ng Mabuting Pastol (the Parish of the Good Shepherd) in Quezon City, the Philippines, is one of the parishes involved in the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program. (Tonette Orejas)

In 2022, Bishop Roberto Gaa established the Diocesan Safeguarding Office for the protection of children and vulnerable adults, complete with protocols documented in a handbook, in response to Francis' call in 2019.

From 2001 to January 2024, the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program has assisted 512 children who experienced physical, mental, psychosocial or sexual abuse. Some were abandoned, lived on the streets or had their live birth registered late. A number received medical or educational assistance. Another 12 cases reached the courts, still undergoing trial.

"Our presence has become good news to children," Abamo said.

"Those directly involved in it are capable of doing basic counseling and managing cases at the levels of individuals, families and parishes," said Baguinon, who has been with the program for 14 years.

But the staff is limited. In the office that serves the Novaliches Diocese and the Manila Archdiocese, the program involves two Salvatorian sisters, five social workers and a lay staff as a financial officer. Baguinon leads the Cebu desk with two lay staffers.

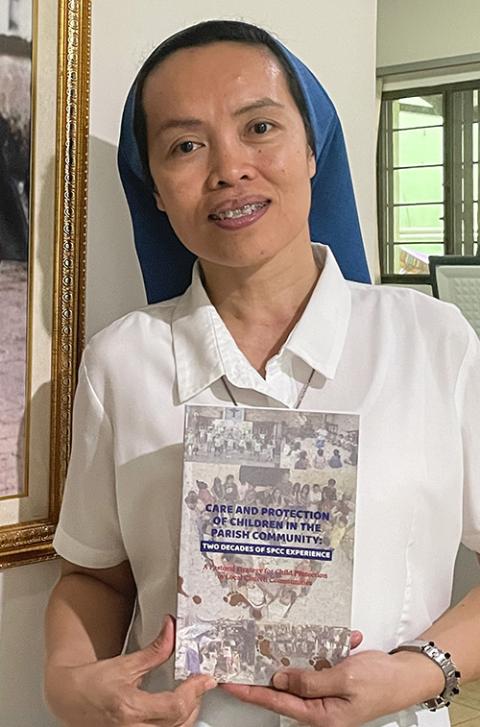

Salvatorian Sr. Ruth Baguinon shows a copy of the book Care and Protection of Children in the Parish Community: Two Decades of SPCC Experience. (Tonette Orejas)

"If a case is beyond our capacity [to handle], we refer it to a network that can do a psychological evaluation. The network provides free legal assistance," she added.

Meeting resistance

The nuns have met resistance along the way.

"Some see or suspect it as a policing of clergy abuse. What we do is we move to dioceses that are more accepting," Baguinon said.

There is ecumenism as well, with the sisters working with other faiths. "The protection of children is an expression of love [for] your neighbor," she added.

The Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children program engages the family because, as Abamo said, "what happens to the family affects the children."

Child rights advocate Flordeliza Genetiano pointed out that the program does not seek to replace the Women and Children Protection Desk of the Philippine National Police or the barangay.

"We bring the cases to the police or barangay desk because they are part of the network. Protecting children is a big task. The diocese or the parish cannot do it alone. We have to work together," Genetiano, 44, explained.

However, more trust is put in the program because it consistently upholds confidentiality, said Abamo, Baguinon, Genetiano and social worker Mary Ann Bernardo.

Assisting children takes three months to three years, as in the case of the victims of clergy abuse. In such cases, Baguinon said the civil and canon laws apply, with the Salvatorian sisters defending the children.

Advertisement

The program also tries to help those assisted to avoid another trauma. The mobile library for book reading on the Gospel and children's rights has toured communities regularly since it began in 2004.

According to Baguinon, they did not stop the program during the COVID-19 pandemic. They used social media and conducted private online consultations, doing counseling face-to-face whenever possible.

Advocates

The program drew several children's rights advocates from former victims.

Wanting to give her son a loving family, Norma Alegre struggled to get past an illicit relationship with a married man who kept her as a mistress for eight years. She remembered the healing as difficult and slow, but Salvatorian Sr. Maricris Tallud helped her emotionally overcome it. With savings from her catering services in the film industry, Norma invested in her son's education and volunteered at the parish children and women protection desk in 2004 as a case manager. She then went full-time after her son graduated from college.

So far, she has handled 100 cases. When discussing a case of a woman who was abused by a priest who was only reassigned to another parish, she did not hide her dismay.

Working in what is now a center for child protection needs clarity of mission, Alegre emphasized, adding, "This is like serving Christ." She gets a small allowance from the parish, but much of the support comes from her son. Now 59, she said she would continue protecting children as long as she can.

Working in a center for child protection needs clarity of mission, case manager Norma Alegre emphasizes, adding, "This is like serving Christ." (Tonette Orejas)

Challenges

Finances are a perennial challenge because funding is on a project basis, lasting three years at the most. Parishes find ways to sustain the work through second collections, fundraising activities or regular budgeting.

"We fear funding fatigue," Abamo said. The program has not yet secured a non-tax status.

The Salvatorian sisters intend to bring the program to more dioceses. The program has shared its experiences with the public in two books and in meetings of the Conference of Major Superiors in the Philippines (formerly the Association of Major Religious Superiors in the Philippines) and the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines.

"I can confidently say that the child-friendly parish initiative is a viable model of a parish-based child and women protection program using the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989) and Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) as major frameworks for advocacy and programming," wrote Leopoldo Moselina, who documented the first decade of the Salvatorian Pastoral Care for Children.

To help expand the program, Baguinon said its personnel can offer consultancy, localized training modules or a mobile training package.

The nuns and the lay staff cope with the rigors and stress of the work through case conferencing, retreat and reflection, Bible sharing or annual conferences. They also hold midyear or year-end evaluations, bonding and creative activities.

"It's a relevant apostolate," Abamo said, with Baguinon cautioning, "It's not an easy work."