St. Joseph Sr. Barbara Moore in 2015 in Selma, Alabama, at the 50th anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: Every two weeks over the next few months, Global Sisters Report will feature interviews with Catholic sisters and former sisters who worked and/or marched in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. We wanted to give these sisters an opportunity to share their thoughts about current racial events, protests and Black Lives Matter. The sisters and former sisters were featured in the 2007 PBS film "Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness for Change" by Jayasri Hart.

GSR invites any sister or former sister who marched or worked in Selma in 1965 to be part of this Q&A series. Email Carol Coburn at Carol.Coburn@avila.edu if you would like to be interviewed.

Sr. Barbara Moore has been here before, marching and protesting for equality. She was among a group of Catholic sisters and one of only two Black sisters who went to Selma, Alabama, in March 1965 to protest the inequality of voting rights for Black Americans.

Moore's roots run deep in Southern soil with family connections in Mississippi, Tennessee and Alabama. A few years after moving to St. Louis, Missouri, with her mother and brother, she converted to Catholicism at age 12.

As a "child of the South," she understood the level of anger and resistance and, ultimately, the danger and risk of her decision to participate in the march. As a Black woman, Moore knew if she was arrested, she would be isolated in a different jail cell, separated from the white sisters. And as she told the Catholic Key, the diocesan newspaper for Kansas City-St. Joseph, Missouri, in January 1990: "The thought hit me that I could easily come home in a box."

Since entering the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet in 1955 as that community's first African-American sister, Moore has made a career of advocating for social justice throughout her life.

"My ancestors built a lot of this country, and after 50 years, there is still discrimination," she told Global Sisters Report. This motivated her to work hard and make a difference.

Moore holds graduate degrees in nursing and sociology and a Ph.D. in higher education administration. Her varied and impressive resume includes health care, academic and social service leadership as well as congregational leadership, predominantly in Kansas City and St. Louis. Moore has also served on many institutional governing boards in Kansas City, St. Louis, and Okolona, Mississippi, and as a volunteer with Nia Kuumba, a spirituality center for African American and African women, and MicroFinancing Partners in Africa.

GSR: Compared to your experiences at Selma in 1965, what do you see as different from the earlier civil rights movement and the more recent events with Black Lives Matter in 2020?

Moore: With the experience in Selma, we had the media to see the brutality while crossing the [Edmund Pettus] bridge. This went out all over — the brutality was shown all over. This is also true of Black Lives Matter.

Selma was very disciplined. The strategies were based on nonviolence, and it was very disciplined. You can't argue with nonviolence and the discipline of the people. We had the "lieutenants" (young Black men) of the movement who told us how to conduct ourselves. You had training before you marched. Someone asked, "What if you can't control yourself?" And we were told, "Then you won't march."

What has encouraged me about Black Lives Matter is it seemingly has gone to many parts of the world, watching and supporting the demonstrations. For me, this is very encouraging because people are beginning to see all the "-isms" that oppress, that there is a relationship among them, whether it is racism, sexism, LGBTQ rights, or other types of bigotry. That's different. If you are comfortable with yourself, you don't have to look down on anyone else.

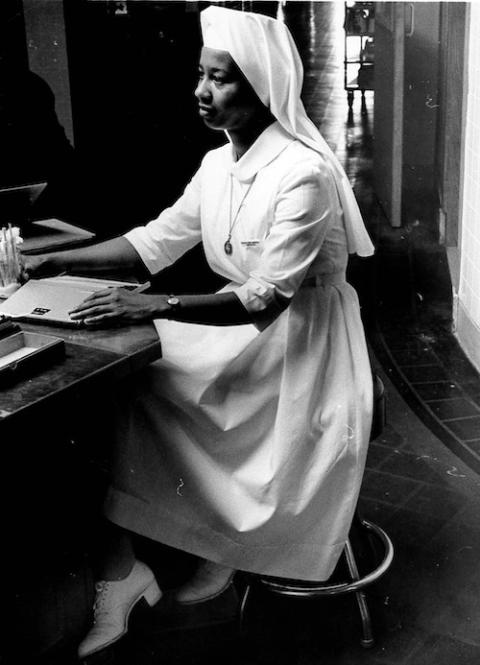

St. Joseph Sr. Barbara Moore in her nursing uniform in the late 1960s, when she was the supervisor on the fourth floor of St. Joseph Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet)

What has changed and what has not changed in the racial climate of the United States? It would appear the media and others use the term "institutional racism" more frequently, which is a much broader concept than thinking about racism as an individual or group action.

[Although there is improvement since the 1960s] we have to look at systemic/institutional changes, and you find institutional racism in education, health care, the penal system, the military, housing, banking practices, etc.

For years, Black leaders have been talking about institutional racism by including other issues. That's not new. People of color are still marginalized because there are still so few in positions of power, and many things haven't changed. It's still a challenge, including clericalism. When it comes to action, that's where it breaks down. Sometimes you get lip service, but little action.

Look at all the systems that are still oppressing people. If you don't have access to education, health care, and a decent job, then institutional barriers are real. Currently, essential workers include many people of color. White people and media are using the term "institutional racism," and that is new to the discussion. They have not focused on this before.

I wanted to understand this concept better, so I studied the online writings and sermons of the Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III, a Protestant minister from Chicago. He addresses all this by explaining the intersection of institutional racism after the death of Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot while jogging in February. I also recommend the book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander.

Are we at a tipping point in this nation? Can we expect real change in racial equality in the immediate future?

This seems to be a reoccurring theme. If people are listening, that's where systemic change comes. We can march and pray, but unless we begin to change — you can say what you want to, but you have to start with yourself.

My priorities for change would be education, health care, and the penal system. Education can prepare you for a job, but if you don't have health care, you aren't going to be able to work. If you can't be healthy morally or physically, you can't be successful. This isn't new, but that is the challenge to the institutional church.

Justice is a pro-life issue going beyond conception and birth. It includes issues such as racism, sexism, education, health care, among others. The march is over. We still have to change.

Advertisement

What is the role of religious communities in this movement?

We need to start with our own institutions. Charity begins at home. Where is my ministry? Where am I serving? Is it just?

If we don't change our own institutions, it's pointless. Start where we are: action, not just praying. I don't believe in criticizing if you're not going to do something. I've been on multiple boards of religious-sponsored institutions and am often the only person of color. For years, I was asked to make suggestions to diversify the board. I would put names forward (Hispanic and Black), and for whatever reason, often, nothing changed.

I have appreciated the many current statements of support for racial justice and police reform coming from religious congregations. Additionally, I respect the work of Shannen Dee Williams, who has written about the historical struggle of Black sisters to be accepted in religious communities and challenges the church to address its racist past. As a founding member of the National Black Sisters' Conference in 1968, I am pleased with its recent statement.

I have noticed the lack of a visible religious presence in the Black Lives Matter marches, so prevalent during the 1960s era. Where are the people of faith? In Selma, religious groups of Catholics, Protestants, clergy, sisters and laity were there, visible to the public and willingly bearing witness to support the cause.

We could really use the influence and leadership of someone like Cardinal Joseph Ritter. He desegregated Catholic schools in St. Louis seven years before the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down segregation in American public schools. He had moral fortitude even though clergy, sisters and other people were opposed to his desegregation order for parish schools.

A group of religious, including Sr. Barbara Moore, sixth from left, traveled from Kansas City, Missouri, to Selma, Alabama, to march in 1965. The group included two sisters from every community in Kansas City. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet)

Any final thoughts? What would you share with young Black Lives Matter activists at this point in time?

You are beautifully and wonderfully made. You have much potential, so take the opportunities you have to actualize those potentials. Know who you are and whose you are.

My hope for the future is that changes will be made to correct the structures and systems that continue to oppress the poor and people of color so that something constructive will come out of this. So that 50 years from now, we are not experiencing the same thing I experienced in Selma and throughout my life.

[Carol K. Coburn is a professor emerita of religious studies and director of the CSJ Heritage Center at Avila University.]