Sr. María Guadalupe Valdez Mora explained to Global Sisters Report the apostolate of working with single mothers. Casa Hogar Franciscana's founder, known as "Libradita" of Arandas, Jalisco, started the first home for single mothers in an abandoned church in 1889. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

On the outskirts of the colonial city of Durango, in Durango state in northern Mexico, far from the historic center with its beautiful cathedral and cobblestone streets, is an industrial area of dusty roads, factories and commerce. Around here, there are few houses and fewer trees. You can catch a sunburn at any hour of the day, and diesel trucks rumble incessantly.

This is where the Franciscans of Our Lady of Refuge established Casa Hogar Franciscana para Mamás Solteras (Franciscan Home for Single Mothers) 25 years ago. Their mission is to guide single mothers to rediscover their dignity and positively integrate into society.

Currently, 25-30 single mothers and their children take refuge in Casa Hogar Franciscana. Although they do not receive any assistance from the government, Sr. María Guadalupe Valdez Mora, a member of the Franciscans of Our Lady of Refuge, told Global Sisters Report, "Divine providence never stops assisting us."

Global Sisters Report visited Casa Hogar Franciscana on a cold November morning and spoke with Sr. Guadalupe about her work with single mothers in Durango.

GSR: Could you tell us about your congregation and your ministry?

Sr. Guadalupe: 100 years ago, pregnant women were disowned by society and their families. Therefore, on June 1, 1889, our founder, Sr. Librada del Sagrado Corazón Orozco Santa Cruz, said, "I want to do something for those girls, and I want to help them."

The archbishop of Guadalajara gave her a church that was almost in ruins. That church had an abandoned house on one side. She began to fix it, and this is where she cared for the first single mother, a young girl whose name was María.

"Libradita," as she was affectionately known, had a focus on education. She asked herself, "These young women are with me, but what do we do with their children?"

In this way, the apostolate of working with single mothers and the apostolate of education began. Today, we have homes for single mothers in Guadalajara, Aguascalientes and the one here in Durango, which has been open since 1998.

Three children staying at Casa Hogar Franciscana play outside on a sunny, cold November morning. More housing will soon be built on this vast open land to accommodate more families in need. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

What services do you offer?

Our focus is on the single mother and her children and women who are psychologically and sexually abused. I mainly seek to form them. First, I ask: Did you finish primary school? Did you finish high school? If not, let's study. Do you want to work? Great, but finish school, otherwise there is no job. I set these rules because getting an education will help them get ahead.

We work with a transversal support network. We collaborate with other institutes, and people come to give workshops, for example, on violence prevention. I also have an institute called CAPA Norte, where the young women receive counseling and psychiatric treatment.

What tasks do the sisters do? What is required of the young mothers? What is a typical day like?

We, the religious, get up at 5:30 a.m. to pray and wait for holy Mass, and then prepare the food. We wake the young women up at 8 a.m. to have breakfast. Not all mothers can attend Mass because they get their children ready for school at 8 a.m. Some mothers, for example, leave work at 2 a.m., and although it is difficult to get up and get their children ready, they have to do it.

After breakfast, they clean the house. Then, they help us cook. We [the nuns] take care of the administration, and always at night when there is silence in the house.

The children arrive from school at 1 p.m. and take a break or play in the recreation area. Afterward, we eat at 2 p.m., and the children rest for a while. At 4 p.m., we help the children with homework, an educational activity or an art project. At 6 p.m., we ring the bell, and everyone, religious, mothers and children, pray the rosary. Then, we go to the chapel and continue praying. We normally ring the bell at 8 p.m. for dinner and then bedtime.

We, the religious, also need our rest after being with them all day.

How do the girls arrive here? Is there a typical case?

Sometimes, we work with the attorney general's office. They bring girls who are 16 or 17 and have children. They help me with diapers and milk, but I provide the rest. Sometimes, Grupo Esmeralda (a family violence prevention program) brings them. And sometimes they knock on our door.

The reality of our society has changed. The girls used to come from the ranchos [rural places], sometimes abused by the father or a relative. Now, we get girls with drug problems. Several of the girls that are with me use modern, dangerous drugs like crystal meth.

These drugs put awful things in their heads that harm them. I tell them that I don't want girls with addictions. But what do I do if they're knocking on my door? The bad thing is that they bring little ones with them.

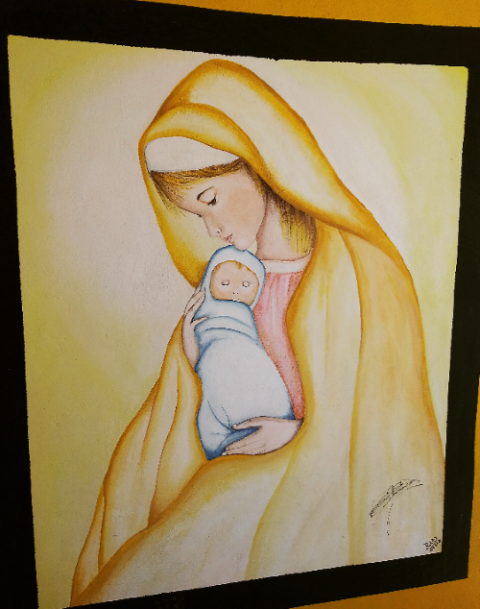

An original design of Sr. "Libradita" on one of the walls outside the bedrooms where single mothers stay with their children. The walls of Casa Hogar Franciscana are decorated with beautiful murals representing pregnancy, femininity, the Virgin Mary and divine love. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

And how have you responded to those changes?

We also have to change with society. I start by learning about their parents. And they are also into drugs. There's a chain. The girl knocking on my door never knew her mother or father, and now that she has children, she wants to break that chain. The goal is to break the chain of violence and abuse. If they don't take matters into their own hands, their child will be another criminal or drug addict.

What other challenges do you face?

The girls don't want to be institutionalized and don't want rules. They want to do whatever they want, and I tell them there are rules here because we're a family. They have their own room and bed, but they have to leave their clothes and room clean and care for their children, but it's challenging because they're not used to it.

They have to want to move forward. If they don't want to, we don't even have to ask them to leave. They leave on their own.

We're with them 24/7. We're three sisters, and it's heavy. In any case, I feel happy doing this work. It's exhausting because we're always educating and talking to them. You have to speak to them clearly, simply and with the truth. Sometimes, I think they don't understand me. They don't listen to me and do the same thing all over again, but we still work with them every day.

The government doesn't help us at all. We have to support ourselves with what people give us, from charity. Therefore, we go to Caritas for food on Thursdays at 2 p.m. Fridays are extraordinary. We host a bazaar, and we attend to people all morning. People come, and we sell them things cheap.

The sisters and families at Casa Hogar Franciscana attend daily Mass in the morning and say prayers in the afternoon in this chapel. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

Could you tell me about a recent case and how you helped them?

I have a 16-year-old girl with a 2-year-old daughter. She impacted me because, at three months, she was already in a DIF foster home. Her mother was a drug addict, and her father never acknowledged her. Her mother had more children, but she gave them away or sold them. They didn't give her and her little sister away. They were put in a DIF home when they were little after being taken from their mother.

When she was between 10 and 12 years old, her grandmother wanted her back. The grandmother took her to a town in the mountains in the northern part of the state [for her safety, I will not give the name] and forced her into prostitution. She says they took her with men over 50. She doesn't like this and goes to the DIF, but they don't listen. Then, she escapes from her grandmother and comes to Durango and enters the DIF, anyway. She prefers to be there, even if it's hard to be hospitalized.

Advertisement

Then, the grandmother says she has custody and takes her back to the mountains. She runs away from her grandmother again but doesn't return to the DIF. She goes to a friend and starts working in a taco shop. Soon, she becomes pregnant. The boy abandons her and is incarcerated for drugs.

In this case, the attorney's office brought her to me because she didn't fit in with the teenagers where she lived because of her daughter. They realized that bringing her here was a way of keeping them together.

I look at that 16-year-old girl and how she carries that life story. She doesn't use drugs, but due to her emotional state, is receiving treatment with a psychologist. The beautiful thing is that she doesn't want the same thing for her daughter and doesn't want to be separated from her.

An altar in the courtyard dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

How did you become a religious, and how did you get here?

I have a dysfunctional family. We're nine children. One spent 20 years in prison, and several others were drug addicts. I am from Guadalajara. Despite that, my mother tried to instill God in us and insisted on taking us to catechism.

I was a teenager when some friends invited me on a missionary trip with the Franciscans. They took us to Nayarit with the Huichols (Indigenous). I dreamed of marrying a person who was also a missionary.

That was my 15-year-old dream. But at 17, God had another calling for me. A sister invited me to her convent. After seeing this beautiful, smiling and happy 60-year-old sister, I thought: What a beautiful life that must be. And I decided to do a 15-day experience. After only eight days, I told myself: I'm not going home.

A priority of Casa Hogar Franciscana is education. Every afternoon, the children of the single mothers do their homework, study and draw in the courtyard with the help of the three sisters. (GSR photo/Jesús Leyva)

I spent two years in Mexicali and nine years in the United States working with migrants, witnessing the pain and reality of our brothers and sisters in a foreign land. Later, I felt called to work with families. I learned more about the family and how to handle teenagers. Then, they sent me here to Durango.

I thank God for my calling. I never imagined I could do work with a social impact.

What have you learned in your time here working with single mothers? Any reflections?

I feel satisfied and happy with our work because you see that a tiny seed is planted in the girls, even those who leave or don't want to be here. Something is left behind, and for me, it will always be a great satisfaction that they leave with a dream or positive thought. For me, that is the greatest payment and satisfaction I can have.

I tell the girls: I know what pain is, but I also know that there is something more to aspire to. I try to instill in them to think beyond.