The body of Sr. Margaret Slachta, foundress of the Sisters of Social Service, is re-interred on Dec. 9, 2021, at the Fiumei Road Cemetery, National Memorial in Budapest, Hungary. (Courtesy of Sisters of Social Service)

"I did not want to leave my country but duty takes me away and will bring me back." These were the words of Margaret (Margit) Slachta, foundress of the Sisters of Social Service, in June 1949 after escaping to the United States from her beloved country, Hungary. Sadly, she was unable to return in her lifetime — however, not without trying.

But Dec. 9, 2021, her remains did return to her home country. The Barankovics Foundation and the National Heritage Institute, an institution of the Hungarian prime minister's office, approached the Sisters of Social Service earlier in the year seeking to have Slachta's body re-interred in Hungary. Their purpose was to honor and celebrate this remarkable woman.

Sr. Margaret (Margit) Slachta, foundress of the Sisters of Social Service (Courtesy of Sisters of Social Service)

In 1920, Slachta was the first woman to be elected to parliament in Hungary. It's now more than 100 years since her election, an event that had great impact on the country into the 1940s when she was forced to leave.

I learned from Sr. Magdolna (Magdi) Kővári, the current general moderator of the Sisters of Social Service, that Slachta had died in 1974 and was buried in Buffalo, New York. According to Kővári, this unusual though compelling request for re-internment in Hungary required much prayer and discernment, and providentially the Sisters of Social Service community with its headquarters in Europe had its general chapter, where such a decision could be made. The sisters of the other two branches in the U.S. and Canada were also informed and their feedback helped the discernment process.

Together in their usual spirit of synodality, they agreed to comply with the request. On Oct. 25, 2021, Slachta's remains were exhumed and transported to Hungary.

At the ceremony of re-internment Dec. 9, 2021, Kővári remarked, "We pay respect for her remains, but we pay homage to her spirit that lives with and among us."

She added that Slachta "brought the ancient ideal of religious life from the desert into the center of life, sending into public ministry consecrated and professionally trained women who serve with modern means, with the power of speech and with preventive legislative action and catholic intent."

To understand the context for this request from Hungary, Kővári suggested that I read the biography Margaret Slachta by Ilona Mona, a Hungarian Sister of Social Service. It was a fascinating read and would make an inspiring film.

Slachta's life was complex, made so by her passionate work for women's rights, political activism and founding a new institute of religious life dedicated to addressing social issues, particularly those impacting families through two world wars and beyond.

She was born in 1884 in Kassa (Kosice), where, according to Mona, the culture of liberalism abounded with little regulation. Religious values were given little attention by society or her family.

But, one day, shopping with her mother and passing a picture of the Trinity, Slachta stopped and asked whose picture it was. When her mother responded: "It's God's," her question was: "Is God not a mother?" Her feminist bent was already being nurtured long before she put it into action.

Attraction to Catholic spirituality was cultivated when she began higher education studies and joined an organization devoted to Mary, Jesus' mother. The organization required a formation year with specific prayers and activities to develop a conscious spiritual life.

In 1906, during the beginning of her teaching career, she met Edith Farkas, a laywoman engaged in the protection of working women in a system called "patronage." Joining a patronage required a commitment to sisterly love, compassion and mutuality of relationship with everyone. No one was to be thought of as "less" than oneself. Each woman was required to be financially self-supporting and to assist in supporting the work of the patronages.

That first "work" was with young women who had been in prison and needed corrective education and skills, and later the mission expanded to a variety of services and advocacy for women's rights in general.

Advertisement

Soon after joining, Slachta became one of its leaders. Her commitment to God and the movement grew and in 1909, on Pentecost, she took vows in Farkas' newly formed Social Mission Society. Although Farkas never took vows herself, she was the recognized superior of the society.

Farkas, as the founder, first promoted formation of the sisters according to the Rule of St. Benedict, and four years later, transferred the spiritual direction of the society to a Trappist monk, whose direction was an extremely strict interpretation of Benedictine spirituality.

This new culture did not match well with the social mission of the sisters, but Slachta diligently followed the will of her superior, even at great personal cost.

Nine years later, Farkas, again, without consultation with the sisters, decided to merge the society with the Daughters of People of the Sacred Heart, founded by a Jesuit. Although advised by a visitator of the local bishop that her decision could divide the sisters up to 80%, she chose to move ahead with the decision.

Slachta and others tried to convince Farkas that the merger was not a good decision, but they were given an ultimatum to either join or be sent away without recourse. No specific number was given of those who were sent away, but those who decided not to join the new venture, although a painful decision, banded together and founded the new Sisters of Social Service in 1923.

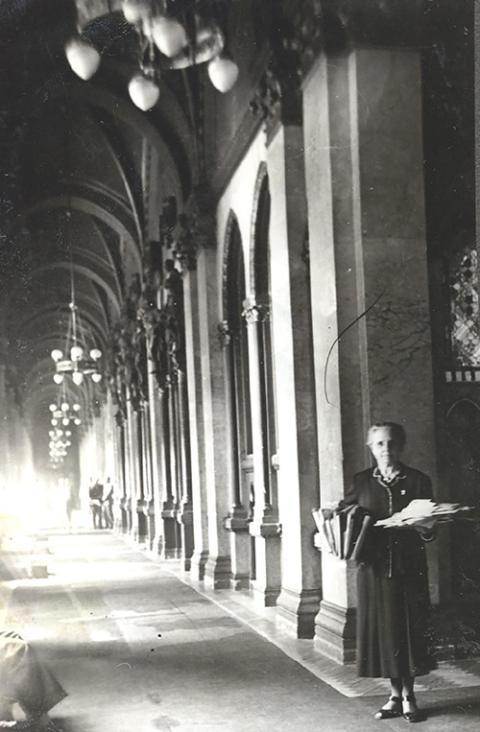

Social Service Sr. Margaret Slachta in the corridors of the Hungarian parliament (Courtesy of Sisters of Social Service)

From the beginning of Slachta's commitment to God and to the social mission, she became a nationally known speaker and prolific writer on social issues of the day, particularly those of women. She also organized women's groups throughout the country to take up their own causes. Around 1914, her external popularity in society and internal influence among the Social Mission Society began to worry Farkas, who eventually decided not to assign Slachta to any Social Mission Society community group.

Slachta was also feared by political personalities who assumed because of her membership in the religious-based organization that she was a spokesperson for the clergy and church. Farkas made it clear however, that the Social Mission Society was not a canonical religious organization.

She explained that even though committed spiritually, the members "in the eyes of the world are not religious; and in the eyes of the church are not lay, only living in the manner of religious common life, and not taking public vows."

Consequently, when Slachta was elected to the Hungarian parliament in 1920 as its first female representative, she did so only with Farkas' permission. She consistently remained in obedience, no matter the cost, which at times was very painful, particularly when in 1922 Farkas did not allow her to accept a second nomination to parliament.

In 1923, obedience brought even more pain when she and the others were dismissed from the society. Nevertheless, Slachta committed herself to the same social mission as a Sister of Social Service and to obedience, following the lead of the Holy Spirit. Pentecost remained the major feast of the newly formed community.

The new community of Sisters of Social Service elected Slachta as their first leader in 1923, but she and the early sisters continued to recognize Farkas as their original founder.

Although having little attraction to governance responsibilities, Slachta held the position as leader for 10 years. Soon after her election she traveled to the United States to visit some of the sisters missioned there and began working with Hungarian émigrés, who, along with others, found her an inspiring and motivating speaker.

Finding community leadership more demanding than she could manage with her heavy political activities, in 1930 she resigned as the community's superior. But two years later, it became apparent that the newly formed community needed her leadership and she resumed the responsibility.

Under Nazi dictatorship in 1944, she and the sisters engaged in the work of rescuing Jews, believing that they needed to do so, even if it brought about their deaths. Sr. Sara Salkahazi was executed in 1944 for following this commitment. The sisters are credited with saving about 1,000 Jews from death.

Slachta also visited the pope to intercede on behalf of the Jews in neighboring Slovakia, where her sisters were working. As a result, the pope ordered the bishops of Slovakia to speak up and deportation was suspended for a time.

The Social Service Sisters were intent on keeping alive Christian social values in their society where dictatorship and communism were making a foothold, and in 1946 Slachta was again elected to Hungary's parliament. She was expelled in 1947 for two months and then resumed her role in 1948 until once again expelled and she lost her political immunity.

Having become a threat to the new communist occupiers, she was forced to go into hiding. Unable to apply legally for permission to leave Hungary, in 1949 friends helped her secure papers under a false name to travel through Austria to Rome and from there to the U.S.

While she was away, religious orders were suppressed and her sisters in Hungary, Romania and other countries were taken into detention. In 1951, desiring to support them, she returned to Vienna, hoping to get back to Hungary from there, but the attempt failed. She was forced to return to the U.S., where she remained in service to the sisters in the U.S. and Canada.

However, at a chapter in 1953, the two groups, U.S. and Canada, proposed separating from the original group and did so in 1955 with the permission from Rome, on condition that they and Europe remain as a federation. As her health declined, Slachta resigned in 1963 as superior general of the original group.

I was awestruck by her story and thought how fortunate the Sisters of Social Service are to have had a foundress who wrote and spoke her ideas so prolifically, boldly and clearly. They chronicle not only the complex development of their congregation and mission but also how timely her work is for today.

Kővári notes this in her comments at the reburial, where she relates Margaret Slachta's thoughts and messages to that of Pope Francis' 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti: "Her ideas, her teachings continue to be alive; they speak to us, they call us to follow, they oblige us."

(The history told here is based on Margaret Slachta by Sr. Ilona Mona, Sisters of Social Service.)