From left: Sr. Pat McDermott; Sr. Margo Ritchie; Sr. Alice Drajea; and Sr. Marie Antoinette Saadé (Courtesy of Sisters of Mercy of the Americas; Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada; International Union of Superiors General)

The International Union of Superiors General continues the first phase of its plenary assembly with an online meeting on April 4. The initial online meeting was held March 14, attended by 465 leaders. The session was recorded, enabling participants to follow on their own preferred time and language. The in-person meetings are in Rome May 2-6 and the final phase is an online session on July 11.

Sr. Jolanta Kafka, president of UISG, opened the March 14 meeting citing Pope Francis on the 50th anniversary of the Synod of Bishops on Oct. 17, 2015. "Synodality — a dynamic of dialogue with the world and humanity is one of the most important processes in the life of the church and today we are called to put it into action as a sign of the times," she said. "In the midst of so much bad news that we are receiving in recent months, this news is one of the most beautiful news that you and I have personally received."

She described a "double movement" in synodality that is, "on one hand a linear movement; and on the other, a circular and communitarian movement." She also cited Pope Francis' encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, that we are called to treat all persons with infinite dignity, that is with "Samaritan care towards the other whom we recognize as my brother and sister."

She then asked three challenging questions for the groups to ponder:

- How are we contributing to the synodal process?

- How do we encourage synodal listening?

- How do we foster common discernment in the church at large?

Reflections from the participants included the following:

"We see vulnerability as a source of hope and truth."

"Not having answers [in this time of vulnerability] … we are like Mary Magdalene at the tomb … and have to 'turn ourselves around' to see the risen Jesus in our midst."

"How do we hold grief and loss while dreaming a new future?"

"As women in the church, we want to contribute our voice, but always have a nagging question … will it make a difference?"

"Our modeling vulnerability not having answers, and telling the truth about our vulnerability is a source of hope and freedom. We are a church that lives without answers. … This is a stance different from 'being in charge. … Now we need one another and all charisms."

Prior to the meeting on March 14, Patrizia Morgante, UISG communications officer, engaged individual leaders in a series of video interviews to explore the theme of "Embracing Vulnerability on the Synodal Journey."

Below are summaries of four interviews: Sr. Pat McDermott, Mercy Sisters of the Americas; Sr. Margo Ritchie, Sisters of St Joseph of Canada; Sr. Alice Drajea, Sisters of the Sacred Heart, South Sudan and Sr. Marie Antoinette Saadé, Congregation of Maronite Sisters of the Holy Family in Lebanon. As I listened to the interviews, I was touched by the sisters' openness and humility.

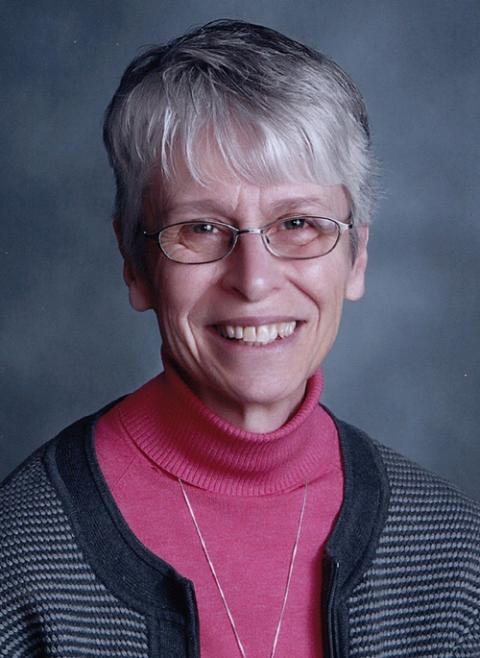

Sr. Pat McDermott (Courtesy of Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

Pat McDermott, president, Sisters of Mercy of the Americas, which includes the continental United States, Caribbean, Central and South America, and Guam and the Philippines

Sr. Pat McDermott spoke about the vulnerability of heart that, through COVID-19, connected her and all of us with the world in unusual ways. All people everywhere, together, experienced the tragedies of death, illness, isolation, fear and uncertainty and at the same time, for others there was the advantage of new ways of connecting with one another through the technology of the internet. She noted that this will be a lasting impact even as we eventually move out of the pandemic.

She also spoke about how vulnerability needs to be welcomed with tenderness, with ourselves and one another and how such relating is a witness of God's presence and our interdependence. As a leader of a large congregation, vulnerability was touched in her as she listened to the stories of personal sadness and the loss, and, when at times the congregation learned of 130 sisters' deaths in one year; notices coming only by email. "It is daunting — over and over to hold a sense of loss."

She spoke of the sadness at the inequities of so many people who did not have the resources or capacities to cope with the sufferings and isolation they were feeling. Recognizing this and being unable to "fix or even make sense of it all brought a deep sense of vulnerability for the sisters" because the Mercy charism of responding to the needs of the poor, sick and uneducated was calling out. But "we were locked up to be safe," isolated from the ones that needed care. As I listened to her, I could feel the anguish of that isolation.

In spite of the restrictions, McDermott told how her sisters in the Philippines and South America did all they could to share the few resources they had with those in need. Mercy leadership at the generalate level also responded by setting aside significant funds for giving sponsored ministries extra assistance and by initiating a creative project in which individual sisters in many places could request $1,000 to assist families they knew were in need. (The Sisters of Mercy partnered with other organizations on a pilot project, Sisters on the Frontlines, which then grew into a larger effort.) McDermott noted that it was "symbolic" assistance, one way of responding to the sisters' desire to welcome the suffering in their neighborhoods. I can imagine even small amounts meant a lot to those who received it.

Sr. Margo Ritchie (Courtesy of Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada)

Margo Ritchie, congregational leader, Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada

Sr. Margo Ritchie noted that at first, she did not resonate with the word "synodal" as something new because she has experienced sisters being engaged with the synodal process and with partnering creatively together for many years. Later, she reflected that it did resonate in connecting the synodal call to respect and embrace diversity, working together for "all of life on this planet." Her first experience of this embrace was at a UISG assembly interacting with sisters from many varieties of religious life. She noted how easy it can be to know intellectually the value of diversity in religious life, but when we experience it viscerally with sisters of different cultures having a common cause to create space where everyone belongs, it feels very real. This call to create space touched her even more deeply when it became a national call: people of Canada being called to make space for people of color and Indigenous who have been pushed to the margins of society.

Along with the depth of this national call, Ritchie added that throughout these years of COVID-19, the word "vulnerability" has deepened in meaning. She described it this way: "It has felt at times like stepping on ground that is not secure, wondering what is next." Everywhere in the world, people are waiting and wanting the new, but that "new" seems to be waiting to reveal itself to us together. For example, in Canada, as the legacy of schools where bodies of children are being discovered, the national identity is shifting. The Catholic Church, particularly sisters, were recognized as the backbone of the Catholic education system, and now they are being called to face the "other" truth, she said. It is "painful coming to terms with this" past. However, the call is clear that the whole nation must "hold it all," in order to "develop a deeper compassion, to face a kind of reckoning with what we were blind to, and now in facing it, to be vulnerable."

Advertisement

She described the recent truckers' protest too, where the people took over the city. "Everything seems out of control. I felt it in my body. We could not keep order or control in our own capital city. How do we make space for protest and dissent?"

When asked what life could come from such grief and sorrow, Ritchie acknowledged that "we can't fix this." We can "learn to listen to experiences of others," take on "a new stance of paying attention, really hearing deeply and in that stance something new will be born." Walking together, she said, "learning to embrace diversity can further the flourishing of our life together."

Sr. Alice Drajea (Courtesy of International Union of Superiors General)

Alice Drajea, superior general, Sisters of the Sacred Heart, South Sudan

Sr. Alice Drajea resonated deeply with the vulnerability theme because in South Sudan, where her congregation was founded in 1954, when the country was still part of Sudan, the Sacred Heart Sisters have lived in vulnerability consistently. In 1963 the sisters were all expelled from Sudan and fled to Uganda without any support. But, committed to their religious life, they were resilient and new life grew out of the disaster. Some returned to Sudan and some remained in Uganda, she said, like "the phoenix rising out of the ashes."

But, today, not much has changed as fragility, war and violence, poverty, and ecological and financial insecurity have continued to be their plight, along with the whole of society of South Sudan. For her and her sisters, an added vulnerability painful to them is that, both in the society and in the diocese, the sisters have "no footing, no voice, no inclusion." She described vulnerability as not being listened to as a person or as a congregation, when decisions made by congregational leadership are ignored and rejected by those in diocesan authority. It seems as though they are "not even recognized as part of the Catholic Church by church authority."

When asked further about personal vulnerability, the pain was palpable in Drajea's voice. The sisters live among the poor who have many needs, and even though desiring to respond, they have few resources themselves to make a difference. The number of refugees and displaced people throughout the country at times feels "out of control" and creates an environment of insecurity. Insecurity then gives rise to fear and blame that is often projected onto the sisters. The sisters feel this burden deeply, but can do nothing to fix things. Part of the projection is the people's belief that the sisters are connected to the resources of the bishop without understanding this is not so. They continue to expect the sisters to do more because they are "church," with access to the "church" resources. The sisters wonder if the tragedy of their two sisters being shot and killed last August coming from the 100-year anniversary celebration of a church service in Sudan was a consequence of this false belief.

COVID-19 has been another painful time. In isolation, the Sacred Heart leaders wondered how they and their sisters could cope with the impact of separation. They had no internet for Zoom meetings like some other groups but they tried their best with phone calls now and again. The leaders were concerned about the well-being of their sisters in Uganda who faced even more restrictions from their government inhibiting them from engaging in any kind of "in person" ministry which kept them very confined.

When asked about her dream of synodality, Drajea said she longs for greater collaboration among religious congregations and healthier intercultural and intergenerational living. It is needed in communities, but also in her nation where there are 64 different tribes and cultures who need the sisters' witness of living peacefully with diversity.

Sr. Marie Antoinette Saadé (Courtesy of International Union of Superiors General)

Marie Antoinette Saadé, congregational leader, Maronite Sisters of the Holy Family

When asked to share the current situation in Lebanon, Sr. Marie Antoinette Saadé responded: "We are actually experiencing a descent into hell. It is the complete collapse of the whole country. … We are struggling with social changes, political issues, corruption, economic crisis. … Our country was once prosperous. The bright and decent people of Lebanon, full of potential, are now reduced to live in poverty." She then said that she feels the UISG assembly theme is prophetic because it joins all of us together. For some, she noted, it has become a "peak of helplessness and impoverishment" and facing it alone is impossible. "We have to stand together."

"On a personal level the theme of vulnerability is very precious," she said. Saadé told stories of two personal conversions at the university as a student. First, when she was introduced to Jurgen Moltmann's book Le Dieu Crucifié (The Crucified God), she realized that not only Jesus suffered and died on the cross, but also the Father, when Jesus cried out, "Why have you forsaken me?" She described this cry as a visceral link of the Holy Spirit between the Persons. Jesus' agonized words reflected the humility of God, giving his life away for us humans. "In front of this God who gives himself, everything becomes relative, everything."

Her second conversion was during her walks to class passing by homeless people sleeping at apartment doors. Her heart ached at the sight because even though she had little herself, as a student, she had enough. She pondered "how much man is capable of to pass by lots of suffering without noticing, without looking at the faces of these people. … I used to stop and to start a conversation with the people, and say to myself, 'This is Christ in front of me who is poor and abandoned.' This is an old experience but it marked my life forever."

When asked about vulnerability as a leader, particularly during the recent COVID-19 years, she related many instances of crises for neighbors and among her sisters on mission. "With many people knocking at our doors … I ask the Lord every day: Take me by the hand. Be in front of me, go ahead, steer this ship, and do not forsake us." She repeated her familiar mantra about the necessity of not struggling through things alone, and practiced this as she tried to stay with her sisters when they also faced discouragement and suffering.

As current president of the national assembly of religious superiors, she travels to visit them and tries to bring encouragement and hope. In the midst of the suffering, gratitude is also the forefront of her prayer and attitude, remembering all the good God has showered on her, her sisters, the country and world. "I cling to this hope despite everything … and not dwell in gloominess."

Morgante asked about her experience of synodality in her congregation and in the church of Lebanon. "This is my second mandate as superior general — my first year of the second mandate [term of office]. In my first six years my main concern was to live synodality." She then described how she continues this commitment as leader of the conference for religious striving for communion with the Lebanon Maronite Church and other religions. In her congregation, synodality remains a major theme. This universal church synod effort has encouraged them forward.

Lebanon, she noted, is a country of pluralism in religion and, because of the country's dire situation, everyone needs to journey together. She recalled Pope John Paul II's description of her country: "Lebanon is more than a country, it is a message" — a message of a country where pluralism is valued, enjoyed and committed to walking together and changing the world together, a world that very much needs changing, promoting the role of women, protecting children and living joyfully. Saadé ended with: "We cannot but be together." It was moving to feel the passion for this working together that Saadé exuded.

It was a privilege for me to listen to these leaders share their stories of tragedy, pain and yet hope that each has found in the unique struggles of these past two-plus years. Also, as I listened I became very aware of the spiritual depth these women were led into as courage, perseverance and love were cultivated.