The Women's March, held in a number of cities around the U.S. in January 2017, kicked off a new wave of protests that have spanned President Donald Trump's first term. Katie Killpack, is pictured third from right, standing at the march in Washington, D.C., with friends. (Provided photo)

Though she didn't know then that her activism would eventually span 50 years, Sr. Gwen Farry's efforts in advocacy began with the grape boycott in the 1960s, handing out fliers outside grocery stores regarding the working conditions of the California farmhands, and later visiting the farms with other sisters and an interfaith group and meeting labor rights activist César Chavez.

Since then, Farry, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, would protest, get arrested, block traffic, stage sit-ins, accept fines. She'd demonstrate against nuclear weapons, the clandestine military training at School of the Americas, immigration laws, cuts to social services.

For the many sisters who, like Farry, have dedicated their lives to fighting injustice, engaging in protests and activism is an expression of faith, a form of prayer in action that helps maintain a sense of hope amidst the often-slow pace of change. Some young activists are adopting those concepts, learning from the vast experiences of sisters regarding effective advocacy and the spiritual dimension of activism — carrying on that spirit in the absence of sisters among today's protesting crowds.

It's been a frustrating time for lifelong activists who are also elderly, as the spring and summer of 2020 in the United States have been characterized by both mass protests against racial injustices as well as the coronavirus pandemic that has claimed more than 210,000 lives in the U.S. (More than 90% of sisters are older than 60, a demographic particularly vulnerable to the virus.) While the restrictions required by the pandemic have stopped Farry and many other sisters from joining protests — spurring them to effect change through petitions and calling politicians instead — some of today's young activists are drawing on the inspiration of women religious as they take to the streets.

Left: Sr. Gwen Farry, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, center, holding a "Stop Deportations" sign, participates in a demonstration outside the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in Chicago in 2015; Right: Farry, center, protests social service cuts that former Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner proposed in 2016. (Provided photos)

Through contact with sisters, including via Nuns and Nones (also called Sisters and Seekers), like-minded young adults have fostered meaningful dialogues and relationships with sisters eager to connect with younger generations. And while the non-sisters may range from atheist to spiritual to Catholic, they're united with sisters in their passion for social justice — or Gospel values, depending who you ask.

"Nuns and Nones is helping me shape my identity as an activist," said 31-year-old Brittany Koteles, the co-director of Nuns and Nones. Though she grew up Catholic, she describes her spiritual inclinations now as "all of the above" rather than "none of the above."

"Sisters have crafted their lives to be of service in the world," she said. As she reflects on her own commitments and the larger purpose, she says, "Nuns and Nones has supported me in continuing to commit on a deeper level."

Her first arrest was with sisters in 2019, when hundreds of Catholics gathered on Capitol Hill for what organizers called a "Catholic Day of Action for Immigrant Children," and 70 Catholic leaders (plus Koteles) were arrested for their civil disobedience while protesting the treatment of immigrants at the border. Though she had for years considered herself an activist, she sensed a different approach to this gathering because of how sisters had orchestrated it.

The language in the correspondence, for example, caught her attention: "It was like, 'an invitation to discern risking arrest' — there is a level of care and spiritual practice that is woven into the action itself," said Koteles, who learned of the event through her local Nuns and Nones group.

Brittany Koteles, left, co-director of Nuns and Nones, takes a selfie with Immaculate Heart of Mary Sr. Joan Mumaw at a 2019 demonstration against the treatment of immigrants at the border. "The whole thing was a literal embodiment of sisters helping us find our way in this fight," Koteles said. "There Joan was, literally showing me the way with her marshal flag, but also, supporting me to show up in the generations-long fight for justice from a place of spiritual groundedness and love for the world." (Provided photo)

"When that happens, the participants are able to more deeply understand their action as an expression of love, and that changes everything."

She recalls feeling a sense of safety and relief that her arrest was alongside dozens of experienced sisters whose "spiritual maturity" changed her experience of the event.

"Oftentimes it's not guaranteed that direct action comes with that source of groundedness, and frankly, I think it's something that movements can sometimes struggle with."

Sr. Susan Wilcox said she found "the Gospel really starts being more alive," once she experienced civil disobedience and being arrested as a sister, much of which was with Occupy Wall Street starting in 2011.

The Sister of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, pointed to a common phrase among activists, of "putting your body on the line"— strikingly Christian imagery from her perspective, she said, "because who put their body on the line more than Jesus did?"

Only then did it occur to her that, "wouldn't this be what everybody who was a follower of Jesus would do, put their body on the line for the poor and oppressed and for injustice or for speaking truth?" said Wilcox, the coordinator of her congregation's Justice, Peace, Integrity of Creation office.

"I had never really been taught that way, so I didn't think that way until I was in it. And then I'm like, oh, wow, this is so Christian."

Advertisement

In a call to transform the world, steadily

Perhaps an explanation for the poetic language of sisters that Koteles noticed around demonstrations, is that the words "protest" or "activist" don't sound right to some sisters.

Wilcox prefers "action, march, demonstration, nonviolent civil disobedience or nonviolent direct action" to the word "protest," which she finds limiting and a bit of a media darling.

And though St. Joseph of Brentwood Sr. Maryellen Kane has protested nuclear armaments, marched for the environment and immigration, and is active in community organizing, she still doesn't consider herself an activist.

"I don't like that word. I think of myself more as a participant in the transformation of the world," she said, or "living out the Gospel." To her, baptism is ultimately a call "to transform the world."

Working closely with sisters through both her job and Nuns and Nones, 29-year-old Rachel Drotar said sisters have taught her that activism is not something you participate in, but rather, integrate into your life.

Drotar is the Generative Spirit program coordinator at the Sisters of Charity Foundation of Cleveland, an initiative intended to cultivate collaborative relationships between sisters and young adults, "looking at a changing church and how justice can be part of that change." Through her work, she discovered Nuns and Nones to be a natural fit for her.

She recalled a recent Nuns and Nones group call in which sisters shared the difficulty of isolation during the pandemic but emphasized how painful it is to not be with those they serve in ministry. Seeing how justice is the center of their lives was, for Drotar, a "wake up call."

"This is the long game, and activism is not really event-based, but more rooted in ongoing work and ministry, guided throughout with spirituality and Catholic social teaching," she said.

Sisters advise that committing to the long haul requires patience, supportive relationships and focus, lest burnout or disillusionment eclipse the mission.

A 34-year-old Nuns and Nones member in New York, Katie Killpack said she used to think yelling was necessary at demonstrations, and that unless you were flirting with burnout, you weren't trying hard enough.

After returning from a Black Lives Matter march this summer and talking to the sisters all revved-up, Killpack remembers the calm demeanor of a sister who reminded her that this work "isn't a flash in the pan" but an everyday obligation, and that she personally found sustenance in contemplative prayer. Since then, Killpack does, too.

On the eighth of what was a 34-day fast, Carmelite Sr. Maureen Foltz, second from left, stands at the U.S. Capitol in February 2006 for the "Winter of Our Discontent" protest, a liquid-only diet call for U.S. peace. She is pictured with veterans Mike Ferner, Bernie Meyer, Jeff Leys and Ed Kinane, who also fasted. (Provided photo)

Sr. Maureen Foltz, a Carmelite Sister of Charity, Vedruna who currently lives in Riverdale, Maryland, said that the ability to persevere is tied to someone's initial motivation.

At any action or civil disobedience, she said, people may gather for different reasons, but "there's a certain essential piece to it for people that connects at the deepest level. And the only word of wisdom that I would give is that the essence of this gift that you carry within you, don't allow it to get a cheapened or dissipate with time.

"There's an essential truth to a lot of what we're living when we're living these experiences of God in the world, and if you have that gift, there's a certain responsibility to care for it in a healthy way."

Foltz's "spirituality of resistance movement," as she said they once called it, began with the U.S. involvement in Central America in the 1980s, which prompted an influx of refugees whom Foltz and her bilingual community tended to with their homeless shelters.

Carrying a banner for the Torture Abolition Survivors Support Coalition, Carmelite Sr. Maureen Foltz, left, in the blue baseball cap, protested the School of Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia, for several years. (Provided photo)

Fear may have been the "outstanding emotion" she felt as a novice in the early days of activism, but eventually, Foltz said she "grew in my sense of indignation. It was a real motivator for me."

And to young activists, she says "make sure your view of the other — be it the policeman in front of you or the president of the United States — doesn't lose their humanity." Without that perspective, Foltz said, it's easy to fall into cynicism, hatred, anger and possibly violence.

"If your premise is that the indwelling of the Divine or the sacred or God or whatever you want to call it, is in the human experience and in the human person, then you cannot say that it's only in some. If it's a premise that you live for, then that's the truth of it."

It's about relationships — and patience

Some sister activists say choosing a particular cause to devote energy to is key to sustaining momentum.

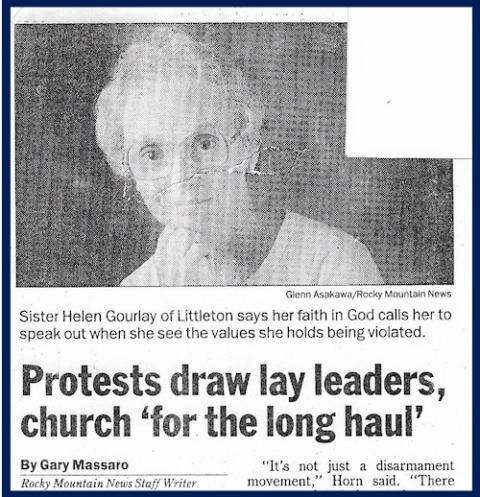

In her 36 years advocating for justice issues, Sr. Helen Gourlay (now 84) said she's learned that focus provides mileage: "I decided that I would focus on one issue and be supportive of others," advice that she extends to young activists who feel tempted to stretch in multiple directions.

Nuclear disarmament was the primary focus for her, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary like Farry. But that didn't keep Gourlay from an array of issues. Though not her focus, she still showed support for other causes by marching and protesting the Gulf War, immigration issues and gun violence, and even going on a peace mission to the Soviet Union. She also participated in demonstrations regarding U.S. policies in Latin America that sometimes led to detainment — the first time she "crossed the line," she said, referring to her arrests. These days, she's writing elected officials, signing petitions, praying and keeping tabs on several issues of interest.

Picking an issue to focus on, said Sr. Maryellen Kane, executive director the U.S. Federation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, isn't a decision so much as a response to the obvious. "They look for you; you don't look for them. … The circumstance of your life determines how and when you respond."

Previously a labor organizer and now a community organizer, Kane said that effecting change boils down to building relationships, as activism is "more about relationships than a particular issue." Once relationships and the organization are in place, "you can go from issue to issue to issue," responding to whatever is immediately affecting the community, she said.

Gourlay noted that, because different roles contribute to the "overall picture," changing roles within a movement is also one way to back off before feeling spent.

Some may be more drawn to public demonstrations that shift public awareness and display solidarity, while others, like Kane, are more compelled to the behind-the-scenes work that works to change systems. In Brooklyn, New York, she was engaged in issues around sanitation, traffic lights, schools and the Nehemiah Housing project, which built 5,000 units of affordable housing in New York City.

"Real change comes through organizing, through the community coming together, dialoging," she said. "It doesn't come about by the big march. That brings attention to it and raises your spirit to know you're not alone, but the actual work is time-consuming and takes a lot more patience."

Sr. Maryellen Kane, executive director of the U.S. Federation of the Sisters of St. Joseph (Provided photo)

It is about being human, and it is enough

Foltz considers engaging in justice issues to be a need for her, a source of "spiritual nutrients" that for other sisters may be found in the Eucharist or quiet prayer. The kind of spirituality that compels sisters to have a framed picture of Jesus, she said, was never one she could relate to; encountering the homeless, however, was "a very deep spiritual experience for me."

"For someone like myself, living in these impoverished neighborhoods among the marginated of the world, and joining them to speak for their rights and being in the streets, that's what nourishes my relationship with God."

Despite no longer considering herself Catholic, Koteles said that the social, spiritual and theological framework that sisters place around this moment and "their duty in this moment" has been orienting for her.

Whether it's from their formation or daily practices, she believes there's "something about sisters" that allows them to "situate this moment in a much longer arc and in the question of what it means to be human."

Drotar sees a lesson in how sisters whose communities are coming to completion look to an uncertain future with more hope than anxiety. The history of sisters — one that responds to the needs and signs of the times — inspires her to think about how she can best apply herself to today's issues, and how "hope can come from evolution."

Sisters have taught Koteles that "hope isn't knowing it's all going to turn out okay. Hope is showing up anyway," following through with your life commitments and "trusting that that's enough."

Screenshot of a Zoom-based Nuns and Nones New York group meeting, showing Katie Killpack at top, center on Sept. 28. The theme was "Seeking Justice: How are people taking action? How can others join them?" (Provided screenshot)

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado. Her email address is ssalgado@ncronline.org.]