Razor wire surrounds Portlaoise Prison in County Laois, Ireland, in January 2021. (Newscom/ZUMA Press/Niall Carson)

When Sr. Eilis Coe visits flats in the inner-city parish of Gardiner Street in Dublin, she regularly checks in on a man in his 40s who recently served a three-year prison sentence for car theft.

The man, who is addicted to drugs and is on methadone, began his prison sentence at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions aimed at preventing the spread of the virus deprived him of contact with a chaplain and his counselor. This lack of support saw him lose confidence to the extent that before he was released, Coe said the man told his father he felt safe in prison and did not want to leave.

"He had lost the will to face out," said Coe, an 80-year-old Religious Sister of Charity. "When he came out, state services told him to get a job, but he is not employable — he hasn't got the stability. He needs some kind of sheltered employment.... His story is that of one young man coming up against the prison system in a time of COVID. He was allowed out with no support. His mother said it was like he was coming out to the wolves."

His partner died while he was in prison, and he had to watch her funeral online, Coe said.

"He saw his little daughter crying at the funeral, 'I want my daddy. My mammy is gone. I want my daddy.' His heart was broken by that," she said. "I am not sure what effect not being able to see her father has had on her. The family pay the debt, as well."

Prison ministry has engaged a significant number of Irish women religious from several congregations in recent years. The Irish Prison Service's 12 prisons employ 25 prison chaplains, 18 of whom are full time. While prison chaplains primarily work with the more than 4,000 people in custody, they also provide support and pastoral care to more than 3,400 prison staff. Because of limited funding, many sisters volunteer as chaplains.

Sr. Eilis Coe of the Religious Sisters of Charity (Sarah Mac Donald)

Before the pandemic, 18 Mercy Sisters ministered in 11 prisons at home and abroad. In Ireland, Mercy sisters have provided hospitality in Cork, Mountjoy, Limerick and Portlaoise prisons and are also involved in ancillary work, including the Bedford Row Family Project in Limerick city. The sisters set up the drop-in center jointly with Franciscan Friars to welcome families of prisoners and ex-prisoners and offer services such as counseling, a children's club, creative writing groups and other support groups for partners of prisoners.

Like the Mercy Sisters, who look to their foundress Catherine McAuley's commitment to the poor and imprisoned, the Religious Sisters of Charity were involved in prison ministry from the very beginning of their foundation, Coe said.

"Prison ministry has been an unbroken chain from the outset, when two sisters visited two women who were convicted of murder in Kilmainham jail in 1815," she said. "Very soon after that, the prison ministry started."

From 2001 to 2021, the average number of people in Irish prisons increased by 20 percent, according to the Irish Penal Reform Trust. In the first five months of 2022, more than 100 people who were released from Irish prisons sought emergency homeless services the same day, The Irish Times reported in August.

Ireland's lack of post-prison services as well as the housing crisis contribute to recidivism, said Sr. Esther Murphy, a Sister of Mercy who served as a chaplain in Wheatfield Prison, a closed medium-security prison for over 600 men in Dublin, for eight years before joining the staff of the medium-security Dóchas Centre in Dublin.

Two part-time addiction counselors work with up to 150 women at the Dóchas Centre, Murphy said.

"They come in from the streets, and they go out to the streets," she said. "There is nothing for them. They are full of intentions of getting into a treatment center, but it is impossible to get a place, and so they gravitate toward those selling drugs so they won't feel the pain of homelessness as much. The systems are not working well for people."

Mercy Sr. Esther Murphy (Courtesy of Esther Murphy)

Murphy also noted that many people enter prisons with mental health challenges and said the Irish penal justice system needs to stop criminalizing those with mental illness if recidivism is to be reduced.

"Prison is not suitable for everyone and not needed for everyone," she said. "There are certain categories of prisoner that it is needed for, but it is not the place for many people, and I think we need to wake up to that fact."

Mercy Sr. Therese Brophy volunteers with the Society of St. Vincent de Paul's Guild of St. Philip Neri, which runs a prison visitation team in Dublin. A former nurse and podiatrist, Brophy told Global Sisters Report tighter restrictions since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic has meant less time with the prisoners — no more than two hours at a time.

"Sometimes, I just listen to them. They like to have a one-to-one," she said. "Their stories can be very sad. I see my role as that of a faithful companion. It means a lot to the women and men that you sit and listen to them and see them as normal human beings — that you don't look down on them. They have slipped because of circumstances... There go I but for the grace of God."

The North Circular Road entrance to Mountjoy Prison in Dublin (Wikimedia Commons/Cograng, via CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sr. Mary Hanrahan of the Presentation Sisters in Ireland, vice president of the Association of Leaders of Missionaries and Religious of Ireland, said prison chaplains are "there in a nonjudgmental capacity, and as we are not part of the punitive system, the men relate easily and openly to us. We are a bridge between the prisoner and the family. We are also there to speak to solicitors and other agencies on their behalf."

After working with the men in Wheatfield Prison, Murphy found the transition to a women's prison daunting.

"The men, generally speaking, were very respectful," she said, explaining that her role involved a lot of listening to the inmates, talking and encouraging them to use the services there for them. "Some of the men come into prison, and they are delighted to get a break. They are off the drugs and drink, they are fed, and they have no bills to pay.

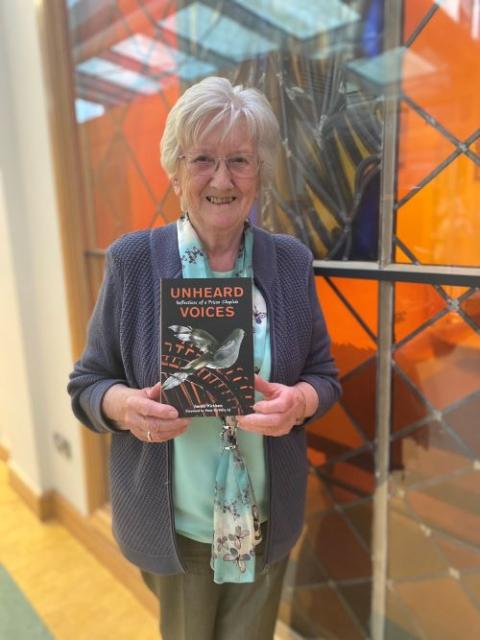

Presentation Sr. Imelda Wickham at the launch of "Unheard Voices" in 2022 (Courtesy of Aoife Kavanagh)

"The women I found to be much more needy," she continued. "When they come into prison, they do a lot of lamenting. A lot of them are mothers, and it is as if the kids are by their side. They beat themselves up all the time because of their addictions.... All I can do is just be there for them, try and give them all the attention, the advice, the listening I can, but I can't work any magic to make anything better. They go out, and there is no place for them to go, and they end up coming back all the time. We see the same cohort of people going out and coming in."

Hanrahan said the main challenges of prison ministry are the lack of resources for the chaplaincy, overcrowding (sometimes four men to a cell), lack of places available in treatment programs for drug and alcohol addiction, and not enough addiction counselors or community welfare officers.

At a May 2022 conference in County Laois titled "The Unheard Voices in our Justice System," Presentation Sr. Imelda Wickham, who worked in prison chaplaincy for 20 years before retiring during the pandemic, called for "a radical updating of the criminal justice system" to bring it into line with the latest advances in cognitive, forensic and behavioral psychology.

"The time to move from our adversarial and punitive system to a more healing and restorative model has long passed. Our whole understanding of human behavior has developed and evolved, and this needs to be taken on board by the criminal justice system," she told the assembled prison governors, politicians, prison workers, and representatives of homeless and addiction services.

Wickham called for a national conversation on developing a more humane system that includes those who carry out crimes as well as their victims.

"Until all voices are listened to and heard, we will continue to paper over the cracks, and we will continue to criminalize the mentally ill, criminalize people who suffer from the scourge of addiction, and criminalize poverty and homelessness," she said.

These, she said, are some of the major contributors to crime.

Advertisement

At the same conference, Jesuit Fr. Peter McVerry, a well-known campaigner on homelessness, said more than 70 percent of those sent to prison have an addiction.

"Most receive little help while in prison and leave prisons still addicted," he said. "Drugs are readily available in most of our prisons despite the best efforts of the prison service to keep them out."

One significant point highlighted at the conference by Ian O'Donnell, a professor of criminology at University College Dublin and a past director of the Irish Penal Reform Trust, was the results of new research in the Netherlands on 4,000 offenders that showed that substituting suspended sentences or community service for short prison terms is effective in reducing recidivism.

Noting that the majority of people sent to prison in Ireland receive short sentences, often less than six months, O'Donnell suggested: "These are the kind of short sentences that could be replaced by community service or suspended with a huge cost saving."

Coe, who has taught creative writing in the Dóchas Centre, said she wonders if prison as a whole is outdated.

"Does prison ever rehabilitate anybody?" she asked. "There is a whole societal and systemic change needed. The main drive must be to keep people out of prison."