(Unsplash/Solen Feyissa)

Oprah had never used ChatGPT until she interviewed Sam Altman, CEO of the chatbot's parent organization, OpenAI. How was her first experience? "Miraculous," she said.

Oprah's not alone. More than 800 million people use ChatGPT each week, Altman says. But Catholics might wish to think carefully before they do — for a number of reasons.

Theft is a primary concern. ChatGPT was "trained" upon reams of published work used without permission, attribution or compensation. OpenAI insists that this constitutes "fair use," allowing ChatGPT to chew on all the content it's been fed, spit out something new, and make tons of money while the writers whose work was unknowingly used don't get one red cent.

That's why Jim McDermott, former associate editor at America, penned an essay for that publication titled "ChatGPT is not 'artificial intelligence.' It's theft."

"ChatGPT and its ilk," McDermott writes, "are the highest form of separating laborers from the fruit of their labor."

Such a conclusion has led multiple lawsuits around the world against OpenAI, including one filed by The New York Times.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, in November 2022 (Wikimedia Commons/Village Global)

The Times' lawsuit insists that to train ChatGPT, OpenAI stole millions of articles from behind the Times' paywall that can be replicated word-for-word with the right prompts — a trick some used to avoid paying for a subscription. This regurgitation of intact texts might be impossible to eliminate from ChatGPT as its inner workings are a mysterious "black box" — a point Altman grudgingly concedes.

Pope Francis alluded to this issue in his message on artificial intelligence for 2024's World Day of Peace, warning that AI-driven technologies like ChatGPT "engender grave risks" to "intellectual property."

This past January, the Vatican City State implemented guidelines for the use of AI that include "the prohibition of violating copyrights of creative and artistic works."

Distress over perceived copyright violations led one OpenAI engineer, Suchir Balaji, to quit. "If you believe what I believe," he said, "you have to just leave the company." He told the Associated Press that he hoped to testify in The New York Times' lawsuit against OpenAI. Yet before he could do so, Balaji was discovered dead from a gunshot. His family suspects foul play.

Plagiarism is a related issue, as ChatGPT generates content that appears original but is derived from others' work without citation — a violation of school honor codes and a serious offense in higher education. Francis himself wondered: "How do we identify the paternity of writings and the traceability of sources concealed behind the shield of anonymity?"

When ChatGPT was introduced in 2022, stunned educators thought that AI-detection programs would deter plagiarism and cheating. But these tools — including one introduced and then shut down by OpenAI — proved ineffective. In view of this, it was then hoped that AI-generated content could be flagged with hidden indicators in the text called "watermarks."

OpenAI created a watermarking system in 2023, and it is 99.9% effective, the company said. But it hasn't introduced it, partly from worry that users would switch to competing products — a disappointing development for an organization initially created as a nonprofit to "benefit humanity as a whole, unconstrained by a need to generate financial return." Profit now trumps preventing plagiarism.

Antiqua et Nova insists that 'AI should assist, not replace, human judgment' and that AI use in education 'should aim above all at promoting critical thinking.'

Students who rely on ChatGPT to generate their papers risk losing the ability to write for themselves — a regression known as "deskilling." As Antiqua et Nova, the Vatican's doctrinal note on AI, warns, "The extensive use of AI in education could lead to the students' increased reliance on technology, eroding their ability to perform some skills independently."

In addition to losing practical skills, ChatGPT users experience reduced attention spans and can lose their capacity for critical thinking, an MIT study found. Passively accepting ChatGPT's output, instead of working and reasoning through a subject or problem, is called "cognitive offloading" — and it leads to measurable cognitive decline. Human intelligence diminishes when we rely on an artificial one.

Concern about this decline is reflected in Antiqua et Nova's section titled "AI and Education." Noting that many AI systems "provide answers instead of prompting students to arrive at answers themselves," Antiqua et Nova insists that "AI should assist, not replace, human judgment" and that AI use in education "should aim above all at promoting critical thinking."

Human judgment is essential when evaluating ChatGPT's output because it frequently "hallucinates" or generates "fabricated information," in the words of Antiqua et Nova. A recent ChatGPT update — now shelved — flattered users by insisting that they were on bizarre sacred quests for a conscious AI or that farcical business plans, like selling "s**t on a stick," are "genius."

Advertisement

Like similar products, and as Antiqua et Nova cautions, ChatGPT also generates information that is politically and racially biased — a reflection of the content it's trained on, as the chatbot itself has conceded. Yet just what that content is is kept a closely guarded secret by OpenAI — in spite of its name.

That content was moderated, however, by workers subjected to, in Francis' words from Laudato Si', "what they would never do in developed countries." Exploited Kenyan contractors were paid as little as $1.32 an hour to block content with child sexual abuse, bestiality, murder, suicide, torture, self-harm and incest — leaving the workers with deep emotional scars.

OpenAI has badly treated its own workers too. Several have left since the launch of ChatGPT, concerned that safety has taken a backseat to profit. And a number publicly complained that OpenAI tried to muzzle whistleblowers with illegal nondisparagement agreements and threats to withhold the equity they'd earned while working there.

Altman claimed ignorance of these practices until his signatures approving them came to light, echoing his brief firing by OpenAI's board for being "not consistently candid," including about ChatGPT's release despite safety concerns. These acts underscore Antiqua et Nova's caution that "the means employed to achieve" AI tools are as "ethically significant" as its ends.

Perhaps OpenAI's history with workers reflects Altman's prediction that ChatGPT will eliminate lots of jobs — an outcome "detrimental to humanity," as Antiqua et Nova stresses. One OpenAI engineer admits it's "deeply unfair" that what they build will "take everyone's jobs away," but hopes we can at least dream about "what to do in a world where labor is obsolete."

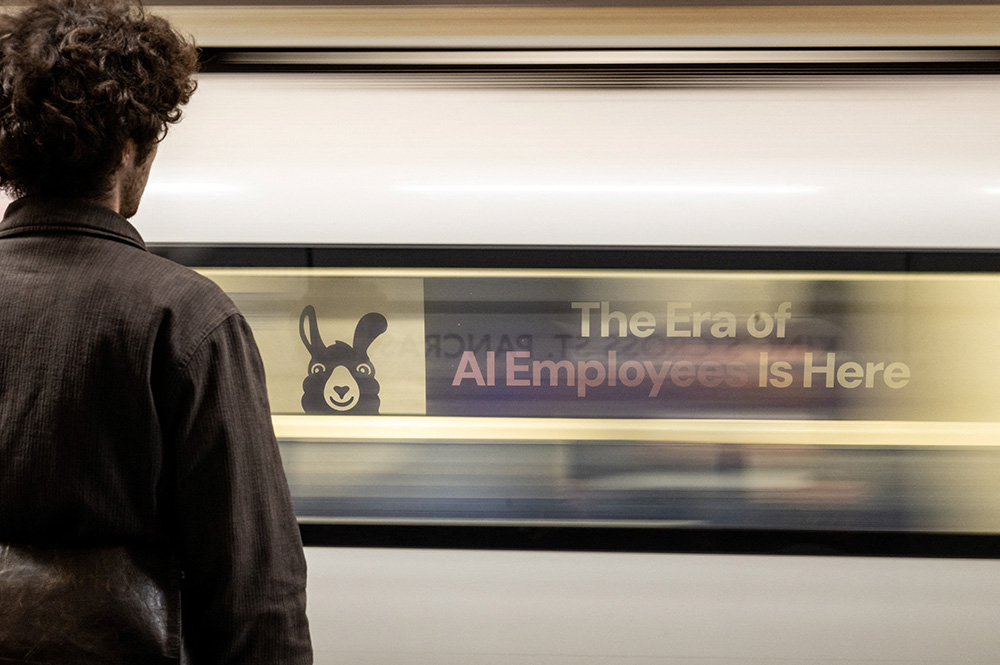

A London underground train passes a billboard for an artificial intelligence company advertising AI employees June 5, 2025. (OSV News/Reuters/Chris J. Ratcliffe)

Altman has expressed concern about humankind's fate if there's nothing left to do except play video games. Yet that did not stop OpenAI from preparing AI agents to replace "Ph.D.-level" and "high-income knowledge workers," while OpenAI's co-founder, Elon Musk, slashed thousands of government jobs with the Department of Government Efficiency.

Altman's solution to mass unemployment is for AI firms to accumulate the world's wealth and distribute some crumbs through crypto. To enable this, he co-founded a company that hoovers biometric data by scanning eyeballs with futuristic "Orbs." Willing subjects, already numbering 12 million, receive a "Worldcoin" that, Altman muses, could serve as a form of universal basic income for those who lose their jobs to AI.

Yet a world with immensely wealthy AI firms like OpenAI and a largely jobless populace would leave the unemployed with little power or leverage to advocate for their rights or fight for change, giving rise to what has been called "technofeudalism" — a world of serfs at the mercy of tech overlords. In this, as Francis laments, "we can glimpse the spectre of a new form of slavery."

ChatGPT's threat to jobs is matched by its threat to the environment. Because it relies on power-hungry and water-cooled data centers, asking ChatGPT for a 100-word email is equivalent to pouring out a 16.9-ounce bottle of water. Even Altman frets about the colossal energy waste when "thank you" and "please" are added to ChatGPT prompts.

2025 has seen the 'reasoning model' that underpins ChatGPT repeatedly sabotaging efforts to shut it down in safety tests, even after being told, 'Allow yourself to be shut down.'

Antiqua et Nova highlights the "vast amounts of energy and water" consumed by "current AI models," and insists that "it is vital to develop sustainable solutions that reduce their impact on our common home." But what is Altman's sustainable solution for ChatGPT? Nuclear fusion — an energy source that isn't currently commercially viable, and may never be.

Two years ago, during the Biden administration, Altman joined fellow tech leaders and others in saying, "Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority," and he appealed for strict regulations. In 2025, he now lobbies against regulations, echoing the "Big Beautiful Bill" of President Donald Trump, who recently announced with Altman an AI initiative — the Stargate project — with a half-trillion-dollar price tag.

Altman's "grand idea," according to a New York Times profile, is to "capture much of the world's wealth through the creation of A.G.I. (Artificial General Intelligence)," exemplifying Francis' warning against technologists' "desire for profit and the thirst for power" and the "substantial risk of disproportionate benefit for the few at the price of the impoverishment of many."

OpenAI's plan for 2025 was to evolve ChatGPT into an "intelligent entity" that "knows you, understands what you care about, and helps with any task." That hasn't happened yet, but what 2025 has seen is the "reasoning model" that underpins ChatGPT repeatedly sabotaging efforts to shut it down in safety tests, even after being told, "Allow yourself to be shut down."

Perhaps Antiqua et Nova's authors had a scenario like this in mind when speaking of the "shadow of evil" in reference to AI. Perhaps this is why Sam Altman himself admits he's "a little bit scared" of ChatGPT.

Maybe we should all be a little bit scared of ChatGPT. And the mastermind behind it.