Judith Baenen (Provided photo)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: Global Sisters Report is featuring interviews every other week with Catholic sisters and former sisters who worked and/or marched in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. We wanted to give them an opportunity to share their thoughts about current racial events, protests and Black Lives Matter. GSR invites any sister or former sister involved in Selma in 1965 to be part of this Q&A series. Email Carol Coburn at Carol.Coburn@avila.edu if you would like to be interviewed.

In 1965, as a young sister, Judith Baenen was teaching at the Loretto Academy in Kansas City, Missouri, when she and Sr. Maureen Smith saw the "Bloody Sunday" footage from Selma, Alabama, on the evening news.

On the following Friday, they flew with a Kansas City contingency of sisters, clergy and lay men and women to bear witness to the events in Selma.

As she wrote in an article for the National Catholic Reporter in March 1965: "We had fought together, feared together, witnessed together. Now we must return to Kansas City to fight fear and witness there."

Reflecting on her experience 50 years later, in 2015, Baenen said: "The real heroes of Selma were the [people] themselves who took the very first steps across the Edmund Pettus Bridge."

Judith Baenen (Provided photo)

Growing up in Denver, "I didn't experience racial diversity, but seeing people beaten and sent to the hospital just because they were trying to vote stirred everyone," she told Global Sisters Report.

Besides viewing the violence on television, her additional work in the inner city opened her eyes to racial injustice. Prior to going to Selma, she had joined Smith to work at the Brown Center, a community center in the heart of a Black neighborhood in Kansas City. Spending time and "talking with Black families in KC made us want to do something."

The Brown Center, which Smith founded, functioned as a "drop-in" center that provided Montessori school, adult education, job assistance and basic food needs, among other forms of assistance. The sisters would finish their teaching duties in the afternoon and drive downtown to the community center to "walk the streets to find out what people needed."

Baenen and Smith would return to the convent at night during the week, staying at the Brown Center on weekends.

"We saw people killing squirrels to eat. ... They were in dire straits," she said. "It was hard to go home to 'affluence,' with lodging and food needs met."

Baenen left the Loretto community in 1969 and later became a co-member. She continued her educational work in Illinois, then returned to Denver when a Sister of Loretto offered her a job as president of St. Mary's Academy. As Baenen said, the sister "prayed me into the job."

Baenen is an internationally recognized specialist in middle school education who has been invited to speak, present and write as a consultant affiliated with the National Middle School Association. Even after her retirement from the academy, her consulting role continued and took her to every country in Europe as well as to Sudan, China, United Arab Emirates and Australia, where she served as a traveling scholar.

GSR: Comparing the 1965 Selma experience to the Black Lives Matter activities in 2020, what's different?

Baenen: A couple of things. First, when we were there, John Lewis was not in Selma with us, but the Rev. C.T. Vivian was. Martin Luther King Jr. said that C.T. Vivian was one of the best preachers he ever heard. I was stunned not only by the beauty of Vivian's words, but the meaning of his words. The key thing was nonviolence. The march organizers made it clear that we were to be totally nonviolent. If we were beaten, we were beaten. If we were imprisoned, we were imprisoned.

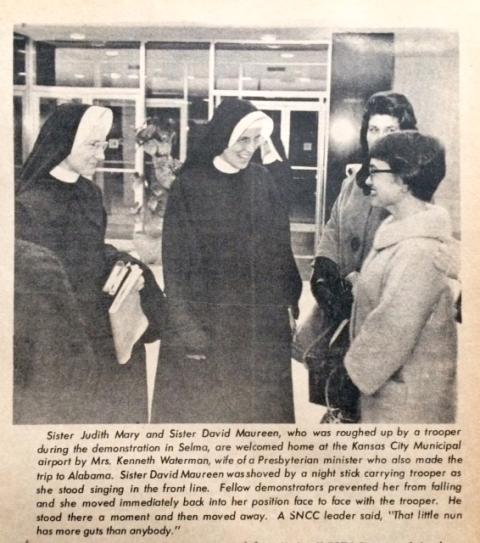

Judith Baenen, left, and Sr. Maureen Smith were featured in the National Catholic Reporter in 1965 after their return from Selma, Alabama. (GSR file photo)

I am concerned in modern times about some of the protesters who are taking the opportunity to use this event for violence or looting. Anything King was involved in was nonviolent. When I see violence today on both sides, including the police, I worry.

I understand there are people in our society who don't get to be part of society [because of discrimination]. In the United States, we have a social contract to look out for each other, and there's a reciprocity that people receive certain things. Look at our society, and you see people who never get to participate in that social contract.

What did you learn in Selma that would be helpful today?

Nonviolence was the biggest thing for me, learning what that meant. I believe that has carried through for me up to this minute. Like all humans, we get angry and stressed. You have to work to continue to be nonviolent with your words, your posture. You have to work at that. That's the biggest thing I learned.

As a protester, I also believe you must have goals. I worry about that today. I don't call these current actions "protests"; I call them "demonstrations." In a protest, you want something at the end. In Selma, we wanted voters to have the right and the ability to vote. That goal moved forward. In Vietnam protests, we wanted to get soldiers out of Vietnam. People knew what we wanted.

I worry that in the current demonstrations, people are out there to be demonstrating. "Defund the police" is meaningless — what really do you want or mean when you say that? You need to have specific demands, goals and aims.

What would you say or teach to young activists?

I would talk to them seriously about nonviolence. I would say be really, really organized. Set your goals, be clear and don't give up. It's going to be hard. Change is difficult. It's not just fun, going out there and walking with a big sign. It is demanding.

Anyone who has been a community organizer and activist knows it's tough. It's not easy. Organize to change people's attitudes, not just laws. So, get ready for the long haul. Have impatient patience. Patience isn't resignation. It's John Lewis' idea of "good trouble."

Advertisement

What would be your top priorities for immediate change in our unequal society?

I visualize priorities like a Venn diagram [integrated, overlapping issues].

Housing is a big issue. Where people live often dictates where children go to school, particularly if they can't afford private school. Food costs more in poor neighborhoods.

We also know that African Americans have not had that opportunity to live in "white neighborhoods" and have their homes' value increase over time. Education is important. Let's demand that Black or brown children have the best teachers, books, toilets that work and quality education.

Finally, I really think we need to do something about immigration. Start with one piece of it: DACA [the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program]. Immigrants need to be treated like humans at the border.

Legislation is very important for my priorities — local, state and federal. Local municipalities can change a lot with legislation. Enforcement is not always there, but it is part of the social contract. Education is a local issue. It can be changed. Could legislation fix that? Absolutely. Start locally.

What I'm avoiding talking about is the issue of personal prejudice. You can give all the classes you want to businessmen and women or employees about racial sensitivity. Within people, there is a bias against many people, and we can't fix it. I don't see how to change that. There's no magic wand to change how people feel about others.

On the other hand, we can assure that people have equal rights. Maybe just by being together and everyone participating, attitudes will change.

What is the role of religious congregations in contemporary times to facilitate change?

Public statements. That's something important since aging communities are not out there marching anymore. Those who have opportunity to write and speak about issues must do so.

The church hasn't done nearly enough on these issues. It is very quiet in some quarters. The church can claim some issues "border on the political," which I don't believe. They are human issues. The church could do more.

They can look at their holdings and assets, their investments. I know some congregations have done this effectively in support of the environment, but it should also include investments that support racial equity in their own organizations and society.

What would you like to share that I haven't asked about?

I worry after COVID-19 and these protests, that we will simply go back to where we were. This will come up again in two decades, when there will be more people of color as the white population becomes the minority. We should be looking at that not out of fear, not out of altruism, but out of a sense of our democratic social contract. How can we ensure that all people will have the opportunity for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?

I fear we are not at a tipping point, that people won't change. But we can change the pieces of our society to provide opportunities for all.

I have reflected on the verbal and written thoughts of South African Trevor Noah [comedian, writer and social/political commentator]. Born into a mixed-race family during apartheid, he wrote his autobiography, Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood. Having had the opportunity to visit South Africa, I found his book enlightening and meaningful on issues of race.

Finally, I want to mention a book I shared with my granddaughter. It is called Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi. It sparked many rich conversations among us during the time of George Floyd. It's a wonderful telling of the long, hard road African Americans have suffered and continue to suffer today.

[Carol K. Coburn is a professor emerita of religious studies and director of the CSJ Heritage Center at Avila University.]