Holy Family Sr. Maria Rani Anthony Pillai, who serves as a conflict counselor in Jaffna, Sri Lanka (Thomas Scaria)

Sr. Maria Rani Anthony Pillai of the Sisters of the Holy Family in Sri Lanka has been a conflict counselor and health worker in Botswana, Pakistan, South Africa, and her native land for nearly 40 years.

The 66-year-old nun from Mullaitivu in Sri Lanka's Northern Province, the epicenter of the country's three decades of civil war, experienced the conflicts of a war that scattered her family. Her grandmother was captured and jailed for six years, and her mother was killed in a tsunami. She could not visit her people for years because of the war in her country.

Pillai spoke to Global Sisters Report about coping with internal conflicts and serving as a conflict counselor in several countries.

GSR: How do you look back on your nearly four decades of ministry among conflict victims?

Pillai: My vocation, ministry and commitment were all rooted in conflict caused by years of uncertainties and war in my country. While fighting my conflicts, I drew some courage and empathy to get into similar situations in Pakistan and African countries. Now, I am back in my country. Whatever I have lost in my personal life, I have gained many times over in my religious life, and I could light a candle and spread some light among victims of conflicts.

How did you cope with the civil war in Sri Lanka?

As a young nun with a lot of enthusiasm, I was involved in peace-building programs by organizing youth in war-affected areas. But my congregation did not want to lose its young nuns in the war, so in 1985, they sent me to Pakistan as a missionary. I served there for almost 20 years. I was outside Sri Lanka during the civil wars, but I lived those conflicting situations by listening to the radio news on Sri Lanka every day.

In those 20 years, what happened to your people in Sri Lanka?

A lot of changes happened in the nation and my family. In 1990, the Sri Lankan army captured Mullaitivu, and the Tamils, including my family members, ran away to interior villages. Some migrated to other countries as refugees. But my grandmother, who was then 70, refused to leave the place. The Sri Lankan army captured her along with many other women and children. Many were raped or killed during captivity. They were used as human shields in war.

When I heard about my grannie's captivity, I asked permission to visit my hometown to get her released. I landed in Sri Lanka in 1995, but despite my pleading and the congregation's intervention, the army did not release her. I returned to Pakistan without meeting her, who was the inspiration for my religious life. I sent several letters to her but received no response. The army released her in 1996 because of her old age. My parents received her from the jail.

Advertisement

Did you visit her? What was her reaction?

Yes, I did. Six months after her release, I visited my family in January 1997 and spent two weeks with her and my parents. My father and Grannie shared stories of war and agonies as well as how God protected them in those crises. Grannie said the army had shown her my letters but did not allow her to reply. Both my father and Grannie prayed over me and blessed me as I left for France for a spirituality course.

My happiness did not last too long. A week after I left them, my grannie died, and a few hours later, my father also died of a massive heart attack. I was still in Colombo as my flight to France was three days later, but the family chose not to inform me and disrupt the France tour. I learned of their deaths a month later in France. I was happy that I could see them while they were alive, but their deaths affected me deeply. I returned to Pakistan after the course.

My tragedies in life did not end there. In 2004, I lost my mother and several other relatives in the tsunami that hit the Sri Lankan coast on Dec. 26, 2004. I was at a two-year counseling course in Kent in the U.K. then and reached Sri Lanka on Dec. 31 to attend my mother's funeral. It was a tough time for me to grieve my mother's loss while consoling my younger sister, who had lost her only son in the killer waves.

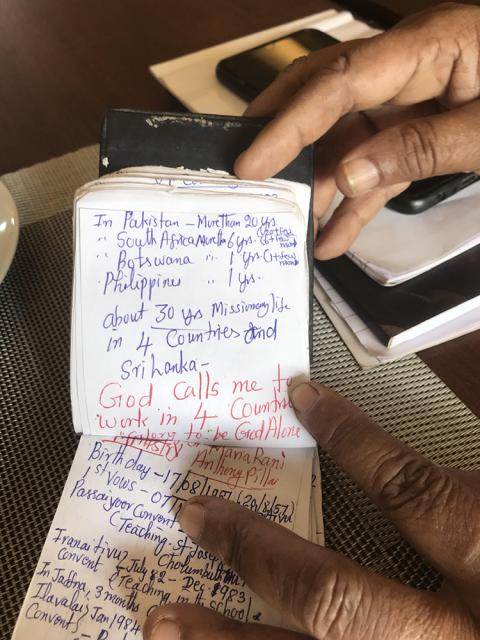

Holy Family Sr. Maria Rani Anthony Pillai, who serves as a conflict counselor in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, flips through a short diary with her missionary milestones from the past 40 years. (Thomas Scaria)

How did you cope with all this and still serve as a conflict counselor and a health worker?

My strength was in fact my own conflicts and losses. I tried to convert each loss into gain for my mission. In Pakistan, I did my nursing and midwife course in addition to counseling unwed mothers and people in conflict zones there. Though Pakistan did not undergo any civil wars like Sri Lanka, they too have experienced several instances of terrorism, gang wars, drug addiction and domestic violence. As a trained nurse, I have assisted thousands of women in their delivery in our mission hospital. I have three generations of people there who were born through my hands.

After I completed my counseling course in London, I opted to work in Botswana and South Africa as a health worker and counselor among HIV/AIDS patients and drug addicts.

When did you return to Sri Lanka?

In 2012, I returned to Sri Lanka, and since then, I am engaged as a conflict counselor and therapist. Though the war ended in 2009, I visit the war-affected families who have lost their people in the conflict. I also worked among tea plantation workers in Sri Lanka to get fair wages. As one of the few trained nurses in my congregation, I also serve our elderly sisters who have withstood several years of conflicts.

What are some challenges you have observed in the conflict ministry?

The challenges were different in each country, but one thing in common was that people did not know how to cope with them. The new generation has few coping skills, and they turn to negative tendencies such as drug addiction, suicide and so on. Even in Sri Lanka, after the war ended, young people have no hope, no jobs and no opportunities. Most have turned to drugs, promiscuous sex lives, and other illegal activities. It is a challenge to bring them back to the positive track.

I have also faced some crises in my life after returning to my country. Although I was effective as a conflict counselor, deep in my heart, I had some guilt that I was not there for my people when they suffered under the civil war, tsunami and the Easter attacks.

How did you deal with the guilt and shame?

In 2015, I attended a healing retreat at the Divine Retreat Centre managed by the Vincentian congregation in Kerala, India, and after that, a healing workshop conducted by the Salesians. These spiritual and therapeutic experiences helped me settle down, and I returned to Sri Lanka with a renewed energy.

My superiors wanted me to return to Pakistan, but the Pakistan government rejected my visa since I had visited India. So they sent me to the Philippines as a missionary. I worked there until 2017. I could not continue there for long, as I was shocked at the police killing of several young people for drug-related offenses. The "shoot on sight policy" of the then-president to curb the drug menace did not reduce their drug problem, but led to chaos there. I returned to Sri Lanka and continued working as a conflict counselor.

Tell us about your childhood and vocation.

I was born in a Tamil Catholic family as third among seven children at Mullaitivu. A year before my birth in 1957, Sri Lanka passed the controversial Sinhala Only Act, followed by the first ethnic riots against Tamils. A year later, the anti-Tamil movement became stronger, and genocide took place in 1958, killing at least 1,500 people, mostly Tamils. So, I have grown up seeing wars all around. My earnest desire to bring peace amid turmoil led me to join the Holy Family congregation that was serving the Jaffna region then.

My parents were happy about my decision, as they thought I would be safer in the convent. In 1982, I did my final profession. A year later, the civil war started between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils.

What are your future plans in Sri Lanka?

I am only 66, and I have a long way to go. My health is not that bad, and I can walk several miles a day to visit our people in their families. I meet youngsters without jobs who are addicted to drugs and alcohol. I know they are not able to cope with their stress and take to drugs and lead a loose moral life. It is challenging to work among them. But they need my service. I believe peace-building should start with individuals and families, and I am there.