One of the 37 "dalle de verre," slab glass windows, capturing the redemptive arc of human and Dominican history, which encircle the Queen of Rosary Chapel at the Dominican Sisters' Sinsinawa Mound in Sinsinawa, Wisconsin (Courtesy of Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa)

If you've ever been the person tasked with cleaning out a family home with the passing of the last of a family's older generation, you have an inkling of the difficult decisions confronting religious communities today. Even as we're diligently working to care for our elderly membership and honor our sisters who are dying at dizzying rates, we are tasked with looking at our legacy of place, space and their treasured contents.

Some congregations have chosen to close the doors to new vocations and, literally, die out with grace. Others, like my own, continue to welcome a trickle of young women with the hope that religious life may yet turn a new leaf. In either scenario, communities must downsize drastically, liquidate unused assets and, often, relocate from the homes they have known.

This change has been a long time coming: trends have been clear for decades and discernment about how to adapt has been ongoing. Nevertheless, in 2022 we have fully arrived at a time when demographics and reality collide. Postponing the hardest decisions is no longer an option. Moreover, this pivotal moment for religious communities is taking place within the context of a destabilized world, what Pope Francis calls not "an era of change" but a "change of era."

Accommodating change inherently requires choosing what to carry forward and what to let go of. Navigating this pivotal moment in religious life during a global era of constant and accelerating change adds layers of complexity to that discernment. Women religious living now are doing this difficult work of discernment even while navigating a broken health care system to arrange for the care of our elderly membership. It is easy to be distracted by urgency and be drawn to obvious solutions for the problems at hand. But sisters in leadership and newer members like myself also long to claim and protect the aspects of our life that matter most deeply.

Sr. Joan Chittister's book Radical Spirit offers some guidance in this discernment. She digs into the spirit of the sixth-century Rule of St. Benedict, articulating a modern interpretation of his timeless wisdom. One rule is particularly pertinent for the crossroads confronting religious communities: "Preserve tradition and learn from community." Preserving tradition is about our legacy to the next generation and how we link the past to the present. Learning from the community is about the collective memory, the deep story that is an essential component for weathering change.

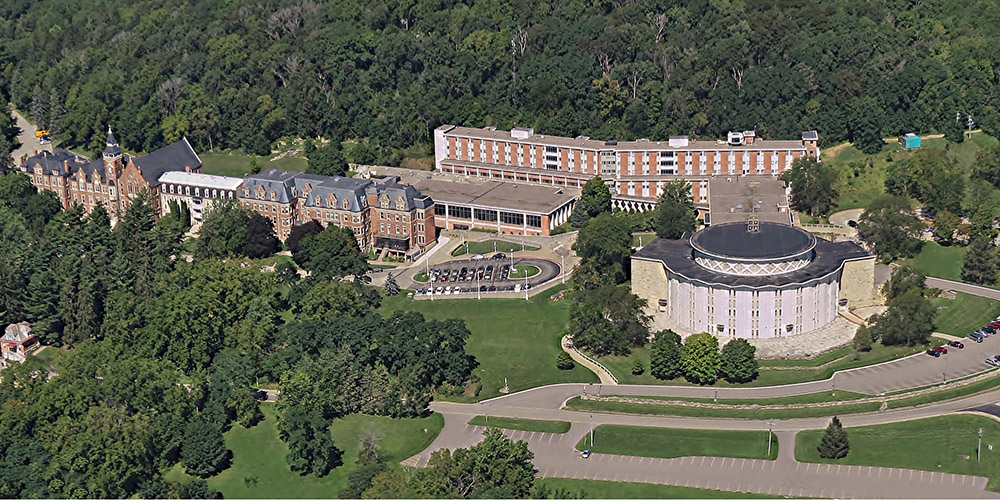

Aerial view of the Sinsinawa Mound (Courtesy of Dominican Sisters of Sinsinawa)

For my motherhouse at the Sinsinawa Mound, the geographic location and the land that surrounds us is bound to our 175-year history and heritage. This has been our home from the beginning. The story of Fr. Samuel Mazzuchelli, our Italian Dominican founder, and his legacy is imprinted across the "driftless area." His story reflects our national history, too, as it related to tribal nations' rights, women's empowerment through education and reconciling with a Civil War. Each congregation has roots in a place, a home that holds its deeper story. Is there a way to build on these stories, carrying them into the future?

The buildings at Sinsinawa Mound are full of sacred spaces. Our Dominican sisters worshiped in the original St. Clara Chapel and, after 1965, we gathered together with God under the dome of the Queen of Rosary Chapel. And then there is the sacred space that the sisters created through their shared daily living. The hospitality, love and joy of 175 years of Dominican women permeates the spaces. Thousands of sisters spent their final years at the Mound, and that presence is palpable.

Each congregation has roots in a place, a home that holds its deeper story. Is there a way to build on these stories, carrying them into the future?

During the final years of her life, Sr. Mariel Blanche Bronson blessed the hallways and the thresholds of the buildings each night–not a small task for 350K square feet of spaces. The buildings themselves incorporate endless artistic features that reflect the deeper story of our congregation's mission and our faith.

For example, 37 dalle de verre, slab glass windows capturing the redemptive arc of human and Dominican history encircle the Queen of Rosary Chapel. They were designed and crafted by our Sr. Teresita Kelly; as were so many artistic effects throughout the sanctuary, reliquary, side chapels, and the Stations of the Cross.

And then there are all of the collectively held things — maintained and cared for over the years with tender diligence. The art, artifacts and musical instruments that are housed at the Mound are astonishing, and reflect the landscape and thinking of a congregation devoted to fine arts education for women. Our collection of painting, prints and sculpture were both gifted to us and created by a rich diversity of sister-artists throughout our history.

Every religious congregation has items that are priceless and one of a kind, things that carry meaning and significance far greater than any auction could capture. I've seen the look on Sister Woods' face, the Sinsinawa director of arts and cultural heritage, when she considers the process of finding the best recipients for these precious parts of our story. American religious communities still have a very strong collective memory, but it is fragile. How and to whom should these treasures be passed?

In this painstaking discernment, the Rule of Saint Benedict equally cautions us from making yesterday a guide for tomorrow. Progress grows out of separating the essence of what should be preserved from the trappings that we are attached to. These attachments often act as barriers, looking to repeat the past or justify preserving what exists, even when it no longer serves. It can lead us to cling to familiarity for comfort, particularly when change is undesired or compelled. The tradition we want to maintain is not so much about what gets guarded or preserved through generations; it is about the passing along of what matters between and across generations.

No doubt, my sisters and I are biased about the value of the beauty and history found at the Mound. Perhaps the design and configuration of the Sinsinawa Mound buildings are simply too unique to serve another purpose. The rural location in the middle of cornfields has not, thus far, been favorable. At least since I joined the congregation in 2014 we have been letting this reality sink in. Deconstructing buildings and returning their footprints to a preserved natural state would be in line with our mission. A cohort of sisters will remain at the Mound, occupying the oldest, smaller-scale structures — a presence more reflective of our numbers and capacity. The surrounding land would be protected from development into perpetuity. This would be an acceptable, responsible outcome as we plan for an unknown future. It would also be a potential shame.

Advertisement

In these uncertain times the world is evolving so quickly that old assumptions may no longer apply. Are there parties with the imagination and capacity to help these buildings serve again? God knows there is no shortage of need in 2022. These buildings, designed around a counter-cultural, community-centered way of life will be newly available in 2023 after the vast majority of our sisters move en masse to a care facility near Milwaukee. As a newer sister I see my role as a placeholder, to help link the past to whatever emerges in religious life. I groan inwardly when confronted by this challenge.

While most religious congregations in the U.S. are facing a similar crossroad, the specific challenges are unique and handled independently (often as a community). But the Vatican is looking to open up the discernment to companionship. In early May, it will host the Charism and Creativity International Conference on cultural heritage, to encourage more shared discernment and creative thinking around plans to preserve what's most important to religious communities.

While robust participation by European congregations is taking shape, there is also a unique value in the cultural heritage of congregations rooted in the U.S. frontier. The pioneer spirits of women's congregations founded in the "New World" helped to bring formal recognition from the Vatican to an emergent model of religious life: vowed women who served God collectively, publicly and actively within communities of need.

While we must let go of religious life as it's existed, others are called by the same mission that calls us. New collective possibilities to live out the faith are emerging all the time. People of goodwill, like the Nuns and Nones, are actively trying to plant seeds of possibility by offering up resources like their Imagination Briefs. These times demand imagination. While the window of possibility is dwindling, there is a promising dynamic that is also part of our deep story: Providence can provide. Providence did provide. Providence will provide. This change of an era must push our creative limits if we are to collaborate around a better, reimagined world.