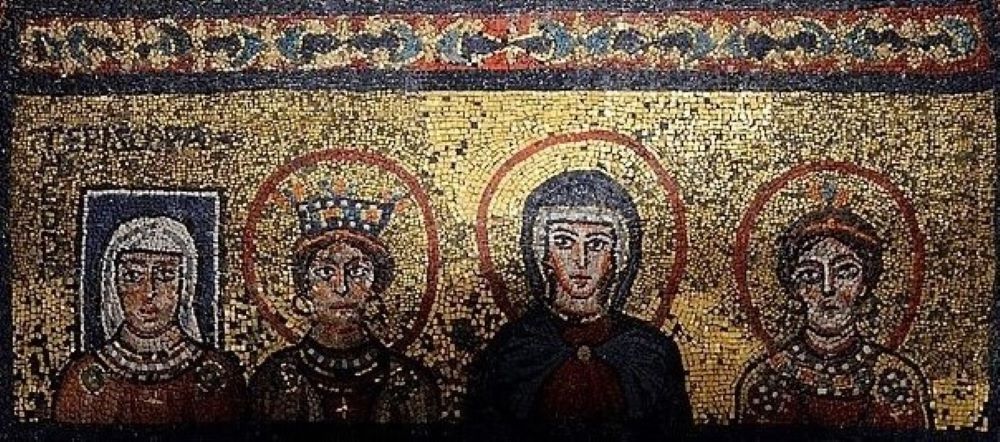

Four women are depicted in a ninth-century mosaic in a chapel in St. Praxedis Church, Rome. (Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

In the New Testament, only Paul mentions so many women leaders with a variety of ministries, such as Phoebe, the deacon of Cenchreae (Romans 16:1); Junia, the apostle (Romans 16:7); and Mary (Romans 16:6), Lydia (Acts 16:11-15), and Nympha (Colossians 4:15), who are heads of house churches, to name a few. He also teaches that through baptism and being clothed with Christ, "there is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female" (Galatians 3:28).

So, if he wants to collaborate with and encourage women, why does he seem to contradict himself with such patriarchal and sexist remarks as when he insists that women in Corinth should have their heads covered for praying and prophesying publicly in their liturgical assemblies (1 Corinthians 11:1-16)? Is Paul trying to resolve a question about women's attire and modesty in ecclesial gatherings and unwittingly imposing rural/semi urban practices on a cosmopolitan community, or rather suggesting that both men's and women's ministries need to be well ordered and mandated?

I'm inclined to believe the latter is true because the thrust of the 11th chapter is to hold ministers accountable for their service. One dispute among them seems to be about female leaders presiding over gatherings in house churches, where they pray and prophesy without any mandate from a male authority. Hence, to please both the camps, he begins by saying that traditions must be maintained (11:2), then describes what is said about authority (11:3-10), and immediately follows by stating that "in the Lord," however, "woman is not independent of man nor man of woman" (11:11).

As apparent from frescoes in the Catacombs, women weren't excluded from any type of ministry before being erased from church (his)tory, for reasons known to us in contemporary contexts, too. Scholars have long been struggling to reconcile Paul's seemingly inconsistent statements about the roles of women. However, when I enter the world within his text with the lens of my vocation as a consecrated virgin, I see a totally different scenario. Both male and female virgins, as well as widows, served the churches during apostolic times and are mentioned by the apostle (7:25-39) before he begins discussing the matter under dispute in his letter.

Paul seems to be tactful, trying to express genuine respect for people's sentiments (9:19-23), while seeking to purify and enhance the quality of their patriarchal culture with Christian values (11:1-2; Matthew 5:13-16). For example, his words: "Christ is the head of every man, and a husband the head of his wife, and God the head of Christ" (11:3) could mean if a virgin is espoused to Christ by receiving the veil, as I shall soon explain, Christ becomes her head, too. This results in equality of status as ministers, irrespective of gender (11:11-12). Hence, to the probable question raised by women regarding the need for men, especially male virgins to also cover their heads, as was practiced in some cultures, he explains why it is unnecessary for them. Moreover, he seems to imply that women who don't receive the veil, and are therefore not dedicated to ministry, must remain silent in the churches as they are subject to their earthly husbands (14:34-35).

Advertisement

This is because the consecration of virgins traditionally involved veiling with the flammeum, as in marriage customs of some ancient churches, although it was a different color. This practice emerged informally during apostolic times but got consolidated as the church was institutionalized over the centuries. Matthew, the apostle, is said to have conferred the first consecration upon Ephigenia, a legendary Ethiopian princess and virgin-saint, with a special prayer. (It is found in the earliest sacramentaries and is still used within the rite as present in the Roman Pontifical, which also mentions the optional veil as a symbol of dedication to the service of the church, as reiterated in Canon 604). The evangelist cherished chastity for the sake of the kingdom of heaven so much that he is said to have been martyred for irrevocably consecrating her against the wishes of the king's successor.

If this is true, Paul would expect the tradition inaugurated by Matthew to be followed in Corinth, as he writes in his first epistle (7:25-38), given the circumstances of the dispute about women's ministry. Although the authorship and sources of Matthew's Gospel could be challenged, the content related to marriage and celibacy (19:11) is parallel to Paul's writings on these themes, which sound like a commentary. Elsewhere, the missionary states, "I promised you to one husband, to Christ, so that I might present you as a pure virgin to him" (2 Corinthians 11:2). His letters reveal in-depth ecclesiology and theology of vocations.

Undoubtedly, feminist virgins were countercultural and resisting pressures to use head covering. I think Paul was trying to introduce the ritual veiling of virgins as a workaround to the problem of resistance to female ministers in the churches. Over the centuries, his instruction was unfortunately misinterpreted and extended to women in general, fulfilling a need for modesty rather than equality in ministry. It's a perennial debate, as seen in Tertullian's On the Veiling of Virgins in the early third century and even today in religious life. Historians write that women in some monasteries that integrated this ceremony of consecration with their profession were authorized to preach the Gospel in liturgical settings. But is that all?

Since the subsequent part of the chapter in Paul's first epistle to the Corinthians (11:17-34) is about issues related to the liturgical gathering, it's possible they celebrate and preside over the Eucharist by virtue of their baptismal calling, irrespective of gender. However, misogynist elements are uncomfortable with women serving equally. This gives rise to disagreements and calls for Paul's intervention, impelling him to state that female virgins must be consecrated and veiled to receive the mandate to serve the church.

Moreover, the pseudo-Clementine epistles concerning virginity, which are addressed to male virgins as well as female virgins of the second century, explicitly mention that their consecration implies they should be Christlike and serve God and the church. The early Christian churches had diverse customs. Perhaps the East and West had varied requirements for women's ministries, and the consecration and veiling of virgins was debated. In the Latin Rite, it was integrated with dedication to the service of the church and was considered one of the 12 sacraments, whereas the Eastern Rites didn't have a ceremony for the consecration of virgins. Instead, they had female deacons as a distinct ministry. This is worth reflecting upon.