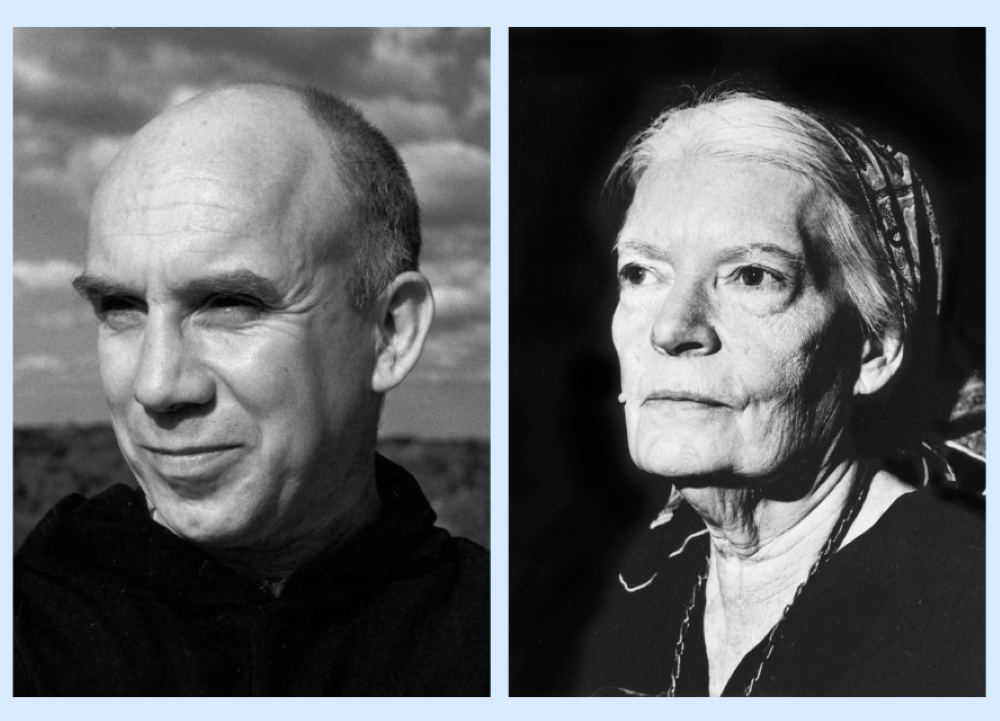

Reading letters between Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton and Catholic Worker co-founder Dorothy Day provided insights into the meaning of friendship and trust, writes Sr. Judith Best, a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame. (CNS photo/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University, (OSV News/CNS/Courtesy Journey Films)

I've recently met some dear friends and realized the blessing of friendship, especially in troubled times. I remember a moment when a friend spoke truth to me when I was in despair. A dear sister, a wisdom elder, looked into my eyes and said, "Judy, not only has the light gone out of your eyes, but the pilot light is out!" Her comment surprised and challenged me. She was truly a soul-friend who allowed me to claim my true self and let go of the pretense of what my mother once described during a short visit to our convent. When I asked how she felt, she said seriously, "I'm dying of terminal niceness!"

Another friend who has spoken truth to me is Thomas Merton. The Trappist monk and writer has challenged me to be my true self, encouraging me to go deep inside to find a deeper wisdom waiting to welcome and guide me.

The ability to hear a challenge and let it free something inside me is the lesson I've learned from reading 33 letters Merton wrote to Catholic Worker movement co-founder Dorothy Day. I gained new insights into Merton, his honesty, and the way he trusted Day, one of his true friends.

One of the gifts Merton has given me is recognizing the mutuality that must have been the foundation of his friendship with Day. He sometimes treated her as his spiritual director, confidante, patron saint of the poor, mother and co-founder in guiding newer people in the radical living demanded at both Gethsemani abbey and her Catholic Worker houses.

Their respective Bohemian backgrounds, including the joys and challenges of unbridled sexuality, intellectual arrogance, living with few boundaries, and basically faithlessness, led them to understand one another in a deep way. Both found their salvation in meeting the poor. In reading these letters I am meeting a new Merton — one who is not as much the teacher as the seeker — rising out of confusion to live with greater stability and kindness.

I need this Merton. He shows me a cleric reaching out to a woman, seeking her advice on possible moves to a simpler place such as living "with the Indians — and Negroes, etc…" He knew of his need to reaffirm his vow of stability, accepting its gifts and limitations, staying where he was.

Advertisement

Day needed Merton's passion for pursuing an inner depth that attracted and evaded her grasp. Amidst the chaos and charm of living in a Catholic Worker community, she tried to model for newer members a lifestyle that both she and Merton struggled to live with integrity.

They both saw the church as woefully out of touch with what Merton called "real people" and needed to speak and write to call companions to a deeper following of Christ, especially the poor Christ. They wrestled with tough questions, such as the self-immolation of Roger LaPorte, to protest U.S. involvement in Vietnam, considering whether to remain a monk or leave to lead the peace movement or other groups, etc.

What helped them both persevere was the witness of others in a centuries-old commitment to follow the poor man of Nazareth and meet the poor of the world on their own turf and in their own words.

What I saw in those letters was an inner restlessness in both their lives. John of the Cross described inner restlessness as spiritual dizziness — a need to jump from one idea or project to another. In Merton, this spiritual dizziness is exemplified in his inner debate regarding moving to another place, finding deeper solitude and being really poor, as inspired by Day's lifestyle. On the other hand, her life included a continuous call to do more — joining another protest, opening new communities, and improving her writing in order to deepen the clarity of current world issues in The Catholic Worker newspaper.

I resonate with this, especially in my middle age years when the idea of moving … anywhere seemed better than teaching bored sophomores. Longing for solitude, the close circles of a religious community didn't seem nearly so exciting as other possibilities like traveling, studying at a university or simply being free to do whatever I wanted. Call it a middle-age crisis, but it seems to have deep spiritual ramifications as well.

During an eight-day retreat in January, my true spiritual director was a Canadian goose who patiently and faithfully sat on her nest throughout all the storms of a cold, snowy winter week. As my retreat seemed less and less satisfying, I remember ending up alone after supper, suddenly aware that I was reading the contents on the Tabasco sauce bottle, hoping for a little "spice" in my life.

Another aspect of Merton that comes through in the letters is his critical attitude toward his abbot, his community members, the hierarchical church — essentially anyone who tried to set boundaries on his desire to accept invitations to lecture, preside at events or research some new possibility for a Trappist mission. I would have found him hard to live with as a community member. I once met a Trappist from Gethsemani who jokingly said: "We could only handle one Merton a century."

At the same time, I see in the letters a consistent plea for conversion, for balance and for a deeper living out of God's will, which both Day and Merton sincerely longed for. They struggled with surrendering to disappointments and misunderstandings, recognizing in these challenges a better plan for fashioning a "true self" or finding contentment in following the "little way" of St. Thérèse of Lisieux and embracing the "dark night" as described by John of the Cross.

Even though Day was 18 years older than Merton, they seemed to share a closeness that was not dependent on age. This resonates with my experience also.

Their respective "complimentary closes" say something about the gradual closeness they shared. His letters to her are signed "Fr. Louis," progressing to "Tom Merton," and finally to "Tom." He addresses her as "Dear Dorothy" throughout their correspondence.

I've met Merton as someone who knew himself and accepted his limits and his potential, all in the context of a sense of humor and God's love.

"Oh Dorothy, I think of you, and the beat people and the ones with nothing, and the poor in virtue, the very poor, the ones no one can respect. I am not worthy to say I love all of you. Intercede for me, a stuffed shirt in a place of stuffed shirts and a big dumb phony, who have tried to be respectable and succeeded," he wrote in a Feb. 4, 1960, letter

Merton has taught me to thank God for all of our friends who love us and who know us, even if we are just "stuffed shirts." The moments shared with dear friends, those who, in their honesty, have had the courage to speak hard truths to me and challenge me, have helped me grow. I thank them for their honesty and their help in claiming my true self. My friends, and even my mother, have kept me from dying of "terminal niceness."