Croatian youth pray for Ukraine, in Belisce, Croatia, Feb. 25, 2022. (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Order of St Basil the Great)

Editor's note: Global Sisters Report's new series, Hope Amid Turmoil: Sisters in Conflict Areas, offers a look at the lives and ministries of women religious serving in dangerous places worldwide. The news stories, columns and Q&As in this series will include sisters in Ukraine, Nigeria, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Nicaragua and more throughout 2023.

I look at the walls of the small kitchen of our monastery (straight lines, stone flowers) and think about how deeply we humans have a longing for harmony and order. As religious sisters, we are used to the fact that from time to time we must change our place of residence or ministry. However, I am sure that the childhood memories still live in each of us: the smells and sounds of the house where we were born and grew up, the bends of the streets of our native village or town, our childhood photos on which the first features of our future adult personality can be seen through amusing faces and disheveled hairstyles.

During this year of Russia's full-scale military aggression in Ukraine, about 40 million Ukrainians were deprived of all these things. For most Ukrainians, their native home has ceased to be a place of security. On 603,700 square kilometers of the territory of Ukraine (which is twice the size of Italy and slightly smaller than the state of Texas), air raid sirens still sound and super-heavy missiles designed to destroy military targets fall on residential buildings.

The funerals of someone's sons and husbands, sisters and mothers take place daily. Those of us who have unexpectedly lost a beloved one or a parent in early childhood can testify to how much it affects our whole life. The deaths of a soldier or a civilian are not just numbers in statistical reports; each of those people was someone's closest person, someone's whole world, a guiding star that has gone out forever.

Sr. Vasylia Sivch, who was, like me, a Sister of the Order of St. Basil the Great, wrote in her memoirs about the Second World War: "Every war is terrible, and the postwar consequences are even more terrible. Whoever experienced them experienced hell on earth. Because everyone was left with deep, painful wounds on the body and in the heart and soul, irreparable losses of dear people and property, acquired by hard work and thrift."

These words sound incredibly relevant even today.

Advertisement

While writing this text, I realized that my previous column for Global Sisters Report was written as early as Feb. 22, 2022, two days before the start of full-scale war. So much happened this year.

At the end of February 2022, the first refugees arrived in the city in eastern Croatia where I lived. I suddenly realized how fragile a human person is, how much he or she needs, and how we do not notice this in our daily life.

Among the refugees, I met a woman with cancer who could not stop chemotherapy; a young girl who needed weekly dialysis; a newborn boy who made his first journey with his mother, who had no opportunity to recover after giving birth. All of them needed not just food, clothes, housing, but very specific medical care, stable conditions, on which their lives literally depended.

If you multiply this by the number of 8 million refugees and displaced persons, you can roughly imagine the scale of the vulnerability caused by Russia's attack on Ukraine.

Soon Ukrainian soldiers who needed eye surgery came to Croatia for treatment. I looked at the burned face of a man who had lost his sight; his hands, also burned, were trembling. With his fragile human body, he stood against the aggressor's weapon to protect us.

We are vulnerable, we are mortal — this is my first lesson this year.

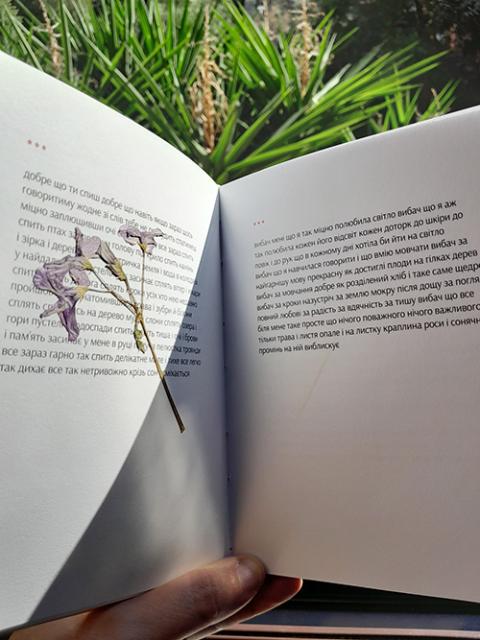

The first book I was able to read since Feb. 24, 2022, was poetry. (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Order of St Basil the Great)

The most difficult thing for those Ukrainians who lived abroad at the time of the start of a full-scale war was the feeling of helplessness, the feeling of guilt due to the inability to protect their relatives who remained in Ukraine. A great support for us was the helping hands of foreign friends who collected aid, accepted refugees, and were simply interested, listened, supported and assured us that they believed in the victory of Ukraine.

A young guy at a printing service who printed my document for free after seeing the Ukrainian flag on it, an old gentleman at a language course who greeted me with "Glory to Ukraine," a library worker who asks me about Ukraine every time we meet — these simple touching gestures were a testimony of humanity and at the same time God's touch. The cracks of fragility in our "clay jars" (2 Corinthians 4:7) made the light of kindness more visible.

The second lesson I learned from this year is that Ukraine, my motherland, is a source of strength for me. Ukrainians who, fleeing the war, found their refuge in Croatia also contributed to this.

The most memorable for me was the question that constantly sounded from the lips of children and adults: "Do you miss Ukraine? Don't you want to return home?" Or as a 4-year-old girl said in her child manner: "Are you Ukrainian or 'Croatinian'?"

This was a lesson for me — to allow myself this longing for home, to trust my longing. Each of us has this yearning for a true "home," for a place where we are accepted, where we can be ourselves.

In August 2022, I had an opportunity to visit Ukraine. And I felt that my homeland, although wounded, was bringing me back to life. The first air raid siren I heard was during the liturgy, when we prayed the creed ("I believe").

And now, when hard moments come, I listen to Ukrainian music and podcasts of Ukrainian psychologists, I read poetry and essays of modern Ukrainian authors.

At the same time, whoever I choose — the brilliant poet Vasyl Stus or the composer Volodymyr Ivasiuk — it turned out that the life of each of them was violently cut short in the war of Russia against Ukraine, which has lasted not only from 2022, nor from 2014, but for several centuries of persecutions, mass deportations and famines.

'God of the kind and quiet, sad and wounded, don't let me unlearn crying.'

—Ukrainian poet Bohdana Matiyash

The third lesson was a spiritual experience. I think that this year brought to both believers and nonbelievers the acute questions about God, about life and death, good and evil, violence and justice.

A priest — to whom I confided that since Feb. 24, 2022, I have felt some obstacles in prayer — advised me to pay attention to how God is working in people during this war. In the courage of Ukrainian soldiers, firefighters, doctors who, risking themselves, fight for human lives every day, we can see a sign of Christ's love, "lay down his life for the sake of his friends" (John 15:13).

However, at the sight of huge injustice, destroyed cities and crippled lives, the question "Why?" inevitably arises. Why is this happening?

The questions remain, they hurt, and sometimes we try to stop feeling and become petrified. The first book I was able to read after Feb. 24 was a collection of poems by the Ukrainian poet Bohdana Matiyash. I read the lines, "God of the kind and quiet, sad and wounded, don't let me unlearn crying," and I cried, for the first time in several months.

... While I am writing these lines, at 10:30 a.m. air raid sirens sound in the entire territory of Ukraine, because in Belarus a plane capable of carrying Kinzhal hypervelocity missiles took off. In those minutes, millions of children left their classrooms or kindergarten playrooms to go down to the basements of shelters. I can imagine how parents feel when they, while going to work in the morning, take their children to school.

My favorite Ukrainian poet and filmmaker, Iryna Tsilyk, whose husband, also a writer, has been in the war for a year, said: "To be honest, I sometimes feel like I carry a big black hole inside me, but fortunately, under the clothes, the smile, and all this things, it is not very noticeable."

While the war is still going on, it is important to stay alive, not to succumb to the temptation of an easy and false peace, to the soothing whisper that "things are not so clear." To remain human, we need to be open to the pain of others and our own. As Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Center for Civil Liberties, aptly put it, "You don't have to be Ukrainian to support Ukraine. It is enough just to be human."

"God of the kind and quiet, sad and wounded, don't let us unlearn crying." God, don't let us unlearn being human.