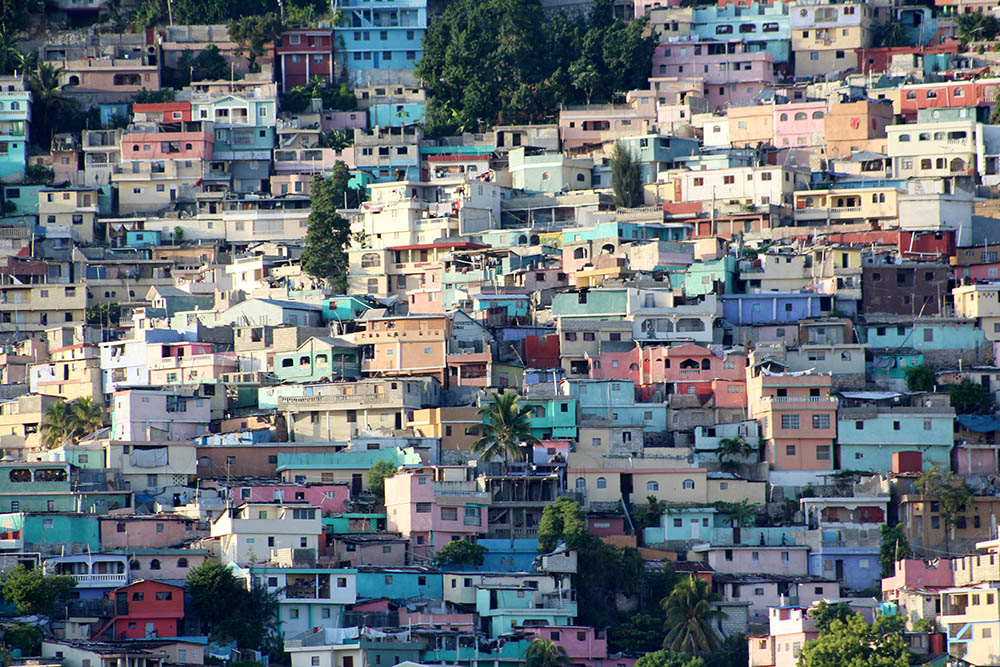

Streets of the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince in 2016. The streets, never safe, are now more perilous because of serious insecurity and the rise of kidnappings and abductions. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Those who read our recent coverage of the unsettled situation in Haiti may recall that in planning for our series "Hope Amid Turmoil: Sisters in Conflict Areas," we opted not to travel to Haiti for on-the-ground reporting.

Why? Haiti is simply too dangerous right now.

Now, some might say: Wait, you've reported from Ukraine in the last year and that's dangerous, right?

Of course it is. But with smart people helping (and in staying away from the "front"), a visitor can navigate and mitigate the danger in Ukraine.

In Haiti, particularly in the capital of Port-au-Prince, the threat is more omnipresent. And a comparison with Ukraine is remarkably stark. As we noted in our main story on Haiti, while 525 civilians were killed in Ukraine during the first three months of the year, at least 846 were killed in Haiti.

Other threats in Haiti can be distilled in one word: kidnappings.

In doing interviews for our recent stories, I was struck by how often the theme of kidnapping came up.

Several people either living in Haiti or with experience in the country told me of their experiences with the threat of kidnapping — a common dynamic in which gangs controlling large sections of Port-au-Prince kidnap people in order to get ransom money. Americans are often targets.

The problem got some attention recently when an American nurse, who is married to a Haitian man, was kidnapped, along with her daughter. Fortunately, the woman, Alix Dorsainvil, and the girl were released after 13 days in captivity.

'I pause, take a deep breath, and step on the gas with the realization I might not be coming back.'

—Gerry Straub

Unfortunately, though, the threat is all too common. According to a recent CNN report, there have been more than 1,000 kidnappings for ransom in Haiti this year.

Gerry Straub, the founder of Santa Chiara Children's Center, a home for abandoned children in Port-au-Prince, told me that he was nearly kidnapped earlier this year and that he is now accompanied by an armed security officer whenever he leaves his compound.

"I pause, take a deep breath, and step on the gas with the realization I might not be coming back," he said. "That is the reality. As this long stretch of barbaric violence continues, people are losing hope."

Straub's near miss with kidnapping came in a larger context. As an American who has lived in Haiti for eight years, he said he has "seen it all."

The hillsides of the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince are seen in this 2016 photograph. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

In addition to the attempted kidnapping, Straub said: "I've had rocks thrown at my car, been chased by motorcycles ... and drove through a wall of fire to get to a hospital."

Jonathan LaMare, chief programs officer for the international nonprofit Mercy Beyond Borders, which was founded by Mercy Sr. Marilyn Lacey, spoke to me of his own experience.

LaMare lived in Haiti from 2012 to 2020. But his organization pulled him out of the country because of two back-to-back kidnapping attempts in October 2020.

One of the attempts was "full-on," LaMare told me — "chased by armed men on motorcycles shooting at us and [going] 120 miles an hour for as far as we could go to get away from them."

Advertisement

LaMare is still involved in Haiti program work remotely — though at a cost. He misses friends and colleagues in Haiti after having invested a lot in the country.

"I had full residency in Haiti," he said. "I mean, I sold everything I owned and moved to Haiti and got residence and learned the language and lived and worked there, almost like an immigrant."

Others from the U.S. have told me similar stories. We shouldn't forget that the fear of kidnapping and insecurity touches everyone. The day-to-day burden of insecurity is borne by Haitians, most of whom do not — unlike outsiders — have the option of leaving the country.

'If any sister goes to Port-au-Prince, I worry and become stressed.'

—Sr. Denise Desil

One Haitian humanitarian worker I interviewed for our stories — and who did not want to be identified out of his own security concerns — said there are all sorts of precautions needed when navigating the streets of Port-au-Prince.

Some areas that are high-crime ("red zones") may not be areas where there are a lot of kidnappings, while areas that may seem otherwise safe — without a large gang presence — can be potential abduction areas. Some parts of the city contain all risks, he said.

A neighborhood where there's a new school opening, for example, may not be controlled by gangs, he told me. "But every part of Port-au-Prince is impacted, as is most of the country," he said. "Everybody's impacted on their ability to travel, which has become now life-threatening."

Commutes are difficult and worrying.

A typical scene in Haiti – men catching a ride on the back of an overcrowded bus. This 2017 photograph was taken on the road connecting the capital of Port-au-Prince with the southern coastal city of Jacmel. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

"It is tough. It's stressful," the Haitian worker said, noting that he is always concerned for the safety of his wife who works in an "apparently calm" area that has a high rate of kidnapping.

One particular worry: People can be stopped by gang members if they are going to a different neighborhood and are asked to show identification.

"If they see that you are from [another neighborhood], anything can happen to you, because that is 'another territory,' " he said.

Congregational members and missionaries have to deal constantly with such threats.

Sr. Denise Desil, mother general of the Little Sisters of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus in Haiti, whose motherhouse is in Rivière-Froide, a suburb of Port-au-Prince, is seen in 2017 during a service of perpetual profession for three new members of the congregation. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Sr. Denise Desil, the mother general of the Little Sisters of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus in Haiti, poignantly told me, "If any sister goes to Port-au-Prince, I worry and become stressed." (The congregation's motherhouse is located outside of the capital city.)

I don't have a dramatic story to tell of my own experiences in Haiti, except to note that during the final day of one of my last assignments to the country, back in 2017, my driver Ulrick and I had to turn back and return to Port-au-Prince because youths were stoning vehicles and burning tires on a main thoroughfare outside the city.

I was disappointed that we didn't make it to the interview I had painstakingly worked out with a group of sisters. (I also felt badly that the sisters had gone to the trouble to make lunch for us.)

GSR international correspondent Chris Herlinger, seen at center with Haitian and Colombian assignment colleagues, including several sisters, in northeastern Haiti during a 2017 assignment (Courtesy of Chris Herlinger)

But my editor, Gail DeGeorge, said I made the right call. And as she noted earlier this year in describing our "Hope Amid Turmoil" series, we've had to put safety "top of mind" when approaching how to cover stories. That means not only protecting our own safety, but the safety of sisters who might host us.

For now, we have to heed the advice of the U.S. State Department in its latest travel advisory: "Do not travel to Haiti," it warned. "Kidnapping is widespread."

To underline that message, the U.S. Embassy in Haiti said Aug. 30 that U.S. citizens in Haiti should leave "as soon as possible."

I hope someday to return to Haiti. In the meantime, GSR's reporting on Haiti continues — though, frustratingly, from afar.