Haitian migrants walk through the forest in Tuxtla Chico, Mexico, Sept. 16 as part of a group of thousands of migrants who were heading to the U.S. border. (CNS/Reuters/Edgard Garrido)

U.S. Catholic sisters and congregational representatives, outraged at the mistreatment of Haitians seeking asylum who tried to enter the United States in late September, say the Biden administration and the U.S. Congress must find a way to enact immigration reform that will embrace humane policies and practices.

In a Sept. 30 interview with GSR, Adrian Dominican Sr. Dursyne "Dusty" Farnan and other sisters and congregational representatives with United Nations-based advocacy efforts under the umbrella of the Justice Coalition of Religious, acknowledged the political difficulties of initiating such efforts.

Comprehensive immigration reform has eluded political leaders in Washington for decades, the sisters and representatives acknowledged, and it may be difficult to achieve in a polarized political climate.

"But if we don't start doing that now," Farnan said of possible new efforts, "this is just going to be repeated over and over and over again."

She cited another foreign crisis, that of Afghanistan, as an example of the need for such reform.

"Right now, we're talking about Haiti, but we have thousands of Afghans who are in the process of trying to be determined whether or not they're really vetted so that they can actually stay here," she said.

While crises like Haiti and Afghanistan will always pose challenges, comprehensive immigration reform that would replace the current patchwork of policies could at least alleviate some of the immigration issues the U.S. currently faces, she said.

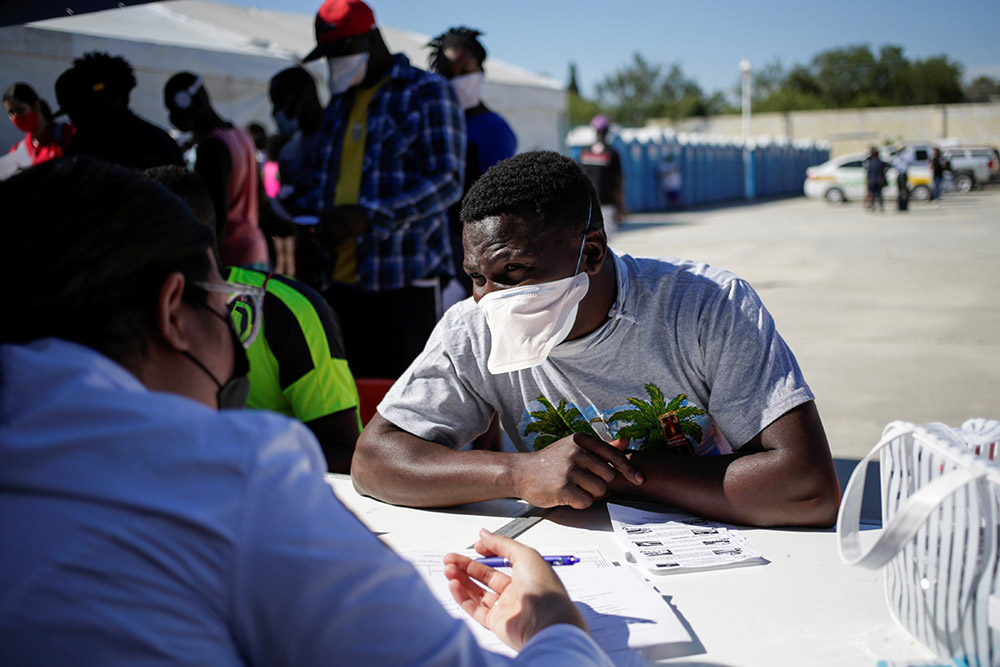

A migrant from Haiti, who returned to the Mexican side of the border to avoid deportation, listens to a health care worker at a shelter set by the National Migration Institute in Ciudad Acuña, Mexico, Sept. 25. (CNS/Reuters/Daniel Becerril)

Such reform must make clear that seeking asylum is a legal right, said Dawn Colapietro, a lay missionary for the Sisters of Charity of St. Elizabeth in New Jersey and who has long experience in Haiti.

"That's the issue," she said. In the recent case of the Haitians seeking asylum at the southern border, "This was not an example of people who were just trying to come to the United States for a better life, but these were people really seeking asylum."

That is a key part of the argument made by the Adrian Dominicans and others supporting a formal statement and letter to President Joe Biden and other top administration officials dated Sept. 28. The letter, condemning the treatment of Haitians at the border, was signed by 177 faith-based groups and 1,947 U.S. faith leaders.

The Adrian Dominican congregation added its own call for the U.S. Congress to enact what it said was a needed "comprehensive and long-overdue immigration reform, which is the only way to provide for rational and humane policies that serve the common good of all."

On the issue of asylum, the congregation, quoting from the letter, said: "Haitian asylum-seekers are not only pursuing what is their legal right. They are also challenging us all to live in full alignment with our religious and spiritual values, which implore us to welcome the stranger and not to turn our back on those in need."

Sisters and others are, among other things, calling on the Biden administration to end flights in which Haitians at the border have been flown back to Haiti, a country facing what many say is an intolerable level of gang-led violence and political and social instability.

Advertisement

"How can you send these people back to a country where there is no governance and there's only gangs? He [Biden] knows that," Farnan said.

Colapietro said there appears to be no difference between Biden administration policies at the border and the "hardline" policies of the Trump administration. That is a grave disappointment to those who had hoped for more humane immigration practices under the Biden administration, she said.

"There's been no change in policy and that's a hard thing — there was an expectation there would be change and the promise of a change. And there hasn't been a change," Colapietro said.

The Sisters of Mercy of the Americas issued its own statement, saying it was joining "with people worldwide in expressing outrage over the shocking treatment of Haitian asylum seekers trying to enter the United States in Del Rio, Texas."

"Haitian women, children and men are among our most vulnerable sisters and brothers," the congregation said in a Sept. 22 statement, noting that Haitians are fleeing a country that, in recent months, "has experienced a political assassination, a massive earthquake and a fierce hurricane."

(President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated July 7, followed in quick succession by an Aug. 14 earthquake and an Aug. 16 tropical storm that later became a hurricane.)

Earthquake victims wait in line for food provided by the World Food Program at a school in Port Salut, Haiti, Aug. 24. (CNS/Reuters/Ricardo Arduengo)

"These catastrophic events further burden a nation with a long history of political upheaval and widespread, grinding poverty, conditions often exacerbated by U.S. policy over the years," the Mercy Sisters said in their statement.

In calling for an end to deportation flights, the congregation urged the administration "to undertake measures to assure that all Haitian asylum seekers have the right to make their case. This right is guaranteed under both domestic and international law."

The expulsion of Haitian immigrants from the border "illustrates just the opposite" of Biden's professed commitment to human rights as the center piece of U.S. foreign policy.

"We must back up bold statements with actions," said the Sept. 28 letter signed by the U.S. faith groups.

According to the letter, that would include ending deportation flights back to Haiti; resuming safe and fair asylum procedures; and holding border agents accountable for abuses against those seeking asylum. It would also involve mean pursuing temporary protected status and other legal remedies "to protect Haitian migrants from harm as they seek refuge from environmental, political, and social strife."

The letter also took on the Biden administration on charges of racism.

"It does not go unnoticed that Black immigrants are often targets of the largest mass expulsions from the U.S.," the letter said, noting that mass migration from the island nation "does not occur simply in response to natural disasters — it is closely tied to harmful, racist U.S. and Western foreign policies toward Haiti going back to 1804 when the country was founded by formerly enslaved people who fought for and won their freedom."

"We must address not only our treatment of Haitian migrants, but also our treatment of Haiti and the Haitian people, and begin to listen to their own solutions for their country's needs."

Among the congregations or sister coalition groups signing on to the letter are the Leadership Conference of Women Religious; the Maryknoll Office for Global Concerns; the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul USA; the Sisters of Social Service of Los Angeles; the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia; the Sisters of the Most Precious Blood; and Sisters, Home Visitors of Mary.

A Haitian migrant is tested for COVID-19 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Sept 20, after U.S. authorities flew him and fellow migrants out of Texas. (CNS/Reuters/Ralph Tedy Erol)

In the Sept. 30 interview with GSR, Indian Sr. Teresa Kotturan, who represents the Sisters of Charity Federation at the United Nations, said she was particularly bothered by the apparent racism on display.

"Color mattered," Kotturan said. "The color of the people who were at the border did matter in the way they were treated. There was no dignity, no awareness that we are all God's children, and they're there out of despair. It was unbelievable, because you have other borders, which they don't resort to this kind of wildland treatment, like cattle being cornered."

Colapietro concurred on the racism issue, saying the photographs and video images of what occurred at the border are emblazoned on her and others' memories.

"I will never get that picture out of my mind of the white man on a horse using his range to whip a black man who's on the ground.

"That picture just encapsulates the history of Haiti and its relationship to the world, and it hasn't changed."

Colapietro and others involved with the coalition have for months been saying that the situation in Haiti – already perilous even in the best of times — has been deteriorating for years because of the rise of gang violence that human rights groups say was due to an alliance between the gangs and the Moïse government.

Colapietro said "crushing violence" is the everyday norm in Haiti now.

"It penetrates everything that people do who can no longer travel, can no longer go to work, can't visit people in the hospital, can't go to the market. The gangs are now posting guards on each end of the market, so you've got to pay a fee coming and going. Vendors have to pay a fee if they want to sell their goods."

"Violence," Colapietro said, "is enslaving Haitians."