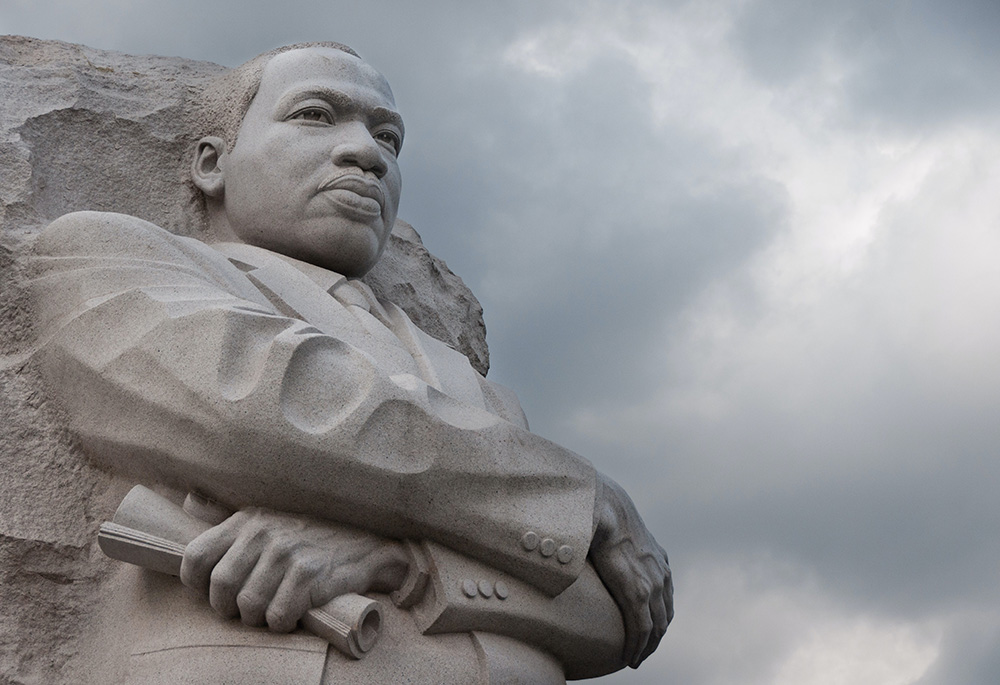

(Unsplash/Raffaele Nicolussi)

Every Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I am bombarded by quotes from the late civil rights icon. On that day, I can't scroll farther than a few posts on social media without encountering the warm sepia tones of photographs showing Dr. King in the middle of an impassioned speech, looking out over a sea of people on the Washington Mall, or linked arm-in-arm with public, civil and religious figures marching in protest for justice.

Every year I am amazed by the pieces of speeches and writings that organizations and individuals share to commemorate Dr. King's life and legacy. There are those that are to be expected — sanitized snippets of King's "I Have a Dream" speech, variations of love lifted up over the burdensome weight of hate, and the moral arc of the universe bending toward justice. These are quotes that make me feel good, that warm the heart and stir the soul in comforting challenge.

Then there are the deeper cuts, the more unexpected or unfamiliar offerings. There was the labor union that pointed that Dr. King, who was assassinated in Memphis, went to the city specifically to help sanitation workers on strike. There were quotes from King's 1967 "The Other America" speech pointing out the racial disparities in the United States, the racism at the root of poverty and economic injustice, and the struggle faced by people of color then and now.

This is the side of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. that is perhaps easier to forget or harder to sum up in simple phrases. These quotes and facts confront popular, rose-colored remembrances of Dr. King and give living color to the nonviolent, Gospel-based pleas (and actions) for justice for which he lived and, ultimately, died.

Reflecting this past week on that disturbing reality, I came across a quote from Dr. King that I had never before encountered. "My call to the ministry was neither dramatic nor spectacular," the brief statement written in 1959 for an American Baptist Convention pamphlet begins. What follows is witness to and reminder of how one's call is cultivated and what the challenge of ministry truly entails.

Befitting the brevity of a leaflet, King's "My Call to the Ministry" is all of 11 sentences and yet in that space, King speaks volumes. His call, like many of ours, was not miraculous. He did not encounter "some blinding light" or have "some miraculous vision." It wasn't sudden, spectacular, or even dramatic. It was, as he writes, "a response to an inner urge that gradually came upon me." This urge, at its core, was "a desire to serve God and humanity." Beyond any mystical experience or prophetic consecration, Dr. King — like any and all believers — experienced the baptismal call to service.

As remarkably unremarkable as it would seem, this was a call that, in King's response, would echo throughout the generations to come.

Advertisement

This call to serve God and others was an urge that wouldn't leave him. It remained as an undying demand on his being, an urge that offered an invitation both of challenge and pilgrimage. That invitation is what lies at the heart of each of our calls to discipleship. We are called to the gradual engagement and witness to God's grace … to the pilgrimage of life. Walking the Way, we discover that some steps are more challenging than others; some realizations and truths demand deeper engagement than we might be comfortable with. These challenges may be to our own views of the world, our own egos, or to the culture that surrounds us.

For King, "the feeling that my talent and my commitment could best be expressed through the ministry" was what prompted the full investment of his being. Committed to faith, he couldn't help but call forth justice. Thus, what organically emerged in the urges of his soul resulted in the prophetic responsibility to cry for God's transformative justice in this land of the free and the home of the brave.

With such courage of conviction, Martin Luther King Jr. followed the urging of the Spirit into ministry and the pages of history. His clarion call for justice and equity is still ringing out if we unclog the ears of our hearts to hear it. It is in the impassioned speeches made for voting rights in and outside of the halls of government. It is in the questions we raise about just wages, safe working conditions, and adequate and equitable housing for all. It is in the commitment we make to create in our church synodal space so that all people's voices are heard and all people are treated as the beloved children of God that they are.

Our call then today is to be attentive to the action the Gospel calls forth in our world and ourselves. We have been called, not by some miracle or accident, but by the grace of God. That call requires action not just remembrance. Just as Dr. King answered the call in his own way and time, now is our moment to respond in-kind, to remember the fervor of our call and to embody the Gospel message in our very lives.

Thus, God's urge for justice comes alive in us and among us and our action gives life to our remembrance. Revealing that the call we answer is a continual act, not just a singular day of the year. For, in the words of Dr. King, "If we do not act, we shall surely be dragged down the long, dark, and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess power without compassion, might without morality, and strength without sight." In brief, we have been called. Let us rise to the occasion of that call.