(Unsplash/Melissa Askew)

In a recent webinar for FutureChurch, Sr. Sandra Schneiders described religious life as a "highly specific way to structure, organize and express one's relationship with Ultimate Reality," a life that is a "total, irrevocable, self-donation to God," … a "single-minded search for God."

We know from Scripture that the God we seek is the God longing to be found, and that we have an innate capacity for genuine and direct experience of God, often called mystical. For some who have experienced spiritual and sexual abuse, whether religious or lay, the light of this capacity for deep connection to wisdom dwelling within seems an impossible dream. For them, mystical experiences are only for special people, not us ordinary or wounded ones. However, theologian Karl Rahner refutes this in a collection of lectures in Theological Investigations, 1961-92. He said it is time to move mysticism from the margins to the heart of being Christian. Thus, any and all wounded Christians are included.

The reclaiming of this light of our innate connection with God may send us back to our childhood where God often begins to invite intimate relationship. In a recent posting Richard Rohr tells his story of a childhood mystical experience in his parents' living room as a 5-year-old at Christmas. Gazing at the sparkling lighted tree, he suddenly knew the world to be totally good and himself to be totally loved. He never told anyone about this, which he notes as an ego decision. He suggests he does not think such experiences are uncommon and then implies it may be time to claim them and share them with one another. They are part of our human experience.

(Unsplash/Jordan Wozniak)

I can vouch for this as I have also had my own mystical moments. One similar to Rohr's also came at age 5. I can still see myself one Saturday in catechism class standing in front of a large poster of Jesus surrounded by children. As I gazed at this picture, I felt filled with love for Jesus and knew myself at the same time, completely loved in return. I felt filled with joy and confidence. For me too, even though it was such an important moment, I never shared it with anyone until many years later. Throughout my life, I have had other such significant moments that have also had deep impact. They are like visitations; suddenly everything is changed, and at the same time, nothing seems changed, as daily life continues.

Rohr doesn't go into the reasons for the importance of sharing such moments but from my own experience and speaking with others, sharing validates them and affirms the spiritual world as real and active, not imaginary. The spiritual world is the air we breathe; the atmosphere of our entire lives. Sharing can also strengthen a deeper communion with others called for by Pope Francis. Sharing keeps us attentive to the fact that there truly is more going on in our lives than meets the eye! Although, we may become more aware of this truth at times of retreat or quiet reflection when we share deep moments of union with God, they do not just come during silent days of retreat. They can come in unexpected ways, even dreams. We can shake them off as being only imagination or unreal, but the "realness" can be detected in the fruits they bear, the changes we might notice in ourselves.

The spiritual world is the air we breathe; the atmosphere of our entire lives.

It seems to me, Rohr implies in his story that openness to the spiritual world can begin in childhood, but is often dismissed by adults and sometimes lost. Another confirmation of this impression after reading Rohr's article came when a friend recently and unexpectedly related to me her experience as a 7-year-old. She started out, "I have never told anyone before" and then told of being at a party in McDonald's where she saw a man, quite disheveled, across the room from her group. She found herself gazing, almost staring at him, and suddenly felt overwhelmed with love for him. At the time, it startled her, but she put it out of her mind and had forgotten about it until she recently read Thomas Merton's account of his experience on a street corner where he knew humankind as holy.

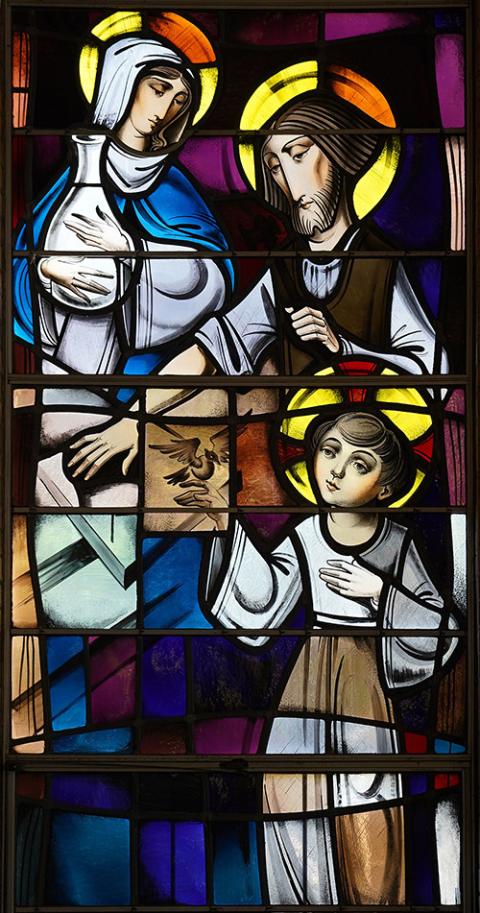

The Holy Family of St. Joseph, Mary and Jesus is depicted in a stained-glass window at St. Joseph Church in Ronkonkoma, New York. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

As I pondered these memories of events in children's lives, Scripture stories also came to mind. We have David as a young person being called by God; Samuel, hearing dreamlike voices directing him to action and, of course, Jesus. Some might immediately be thinking, "Oh, but they were special, especially Jesus." However, as I reflected on the story of Jesus being lost to Mary and Joseph during a trip from Jerusalem, I came to a different conclusion. After all, Jesus was like us in all things except sin. When Mary and Joseph discovered him missing they searched for him. At last they found him in the temple, a mere 12-year-old, teaching the priests. Their first reaction was annoyance, a typical parental reaction. They scolded him for causing them worry. But they were also puzzled and astonished, "Where did he get such wisdom?"

Jesus doesn't argue, only says he was doing what his Father asked. Then, he seems to shut down and goes home with them to live an ordinary life. The Gospel writer does say he "increased in wisdom" (Luke 2:52) perhaps the fruits of other spiritual experiences, but it seems he kept those to himself as so often happens with us. But, later as an adult, Jesus could say with confidence that "unless you change and become like little children you will never enter the kingdom of Heaven" (Matthew 18:3). Somehow, in those years he came to inner clarity that the kingdom is already present among us, not a place far away. We live in it, but we are out of touch with it.

Throughout Scripture, there are warnings to "stay awake" to God's presence, and if we're not paying attention, we miss those moments.

I wanted to find out more about this tendency to "be asleep" or forget childhood spiritual/mystical experiences. An online search showed that others had also wondered about children's spirituality and have written about the topic. The book that really caught my attention was The Secret Spiritual World of Children by Tobin Hart, a psychologist and founder of the ChildSpirit Institute. The book was inspired by an experience his 6-year-old daughter shared with him about her angel companions. He could tell from her description that her experiences were not just imagination, but something truly spiritual because she spoke about the peacefulness and sense of being loved she received from them.

He pursued his study of the spiritual life of children, later surveying and interviewing numerous adults and discovered that a high percentage of respondents had spiritual/mystical experiences as children. Most had not shared them until asked. A conclusion Hart came to, as he listened to their stories and the impact of adult reactions to their telling, was that if children see an adult whose face or reactions register fear or confusion, they usually shut down, keep quiet, or dismiss the experience as not real.

Studying classical mysticism and mystics, and through interviews with children, Hart realized that children's spiritual moments were similar to those described by the mystics. For some, these moments became touchstones of lasting impact, expanding understanding of self-identity and/or place in the universe, or openness, even as children, to a deep compassion, as I noted in the story of my friend. And, at times, the moments led to deep wisdom and insight — as Hart writes, "seeing beneath the surface of the material world." These were invitations to "dwell as near as possible to the channel in which our light, or spiritual essence, flows."

The spiritual being is alive in us at all times if we are attentive.

I imagine most of us have listened to very young children say extremely wise or insightful things and have wondered how they could have such understanding and insight. In his book, Hart shares many stories of adults hearing children who asked deep questions as they searched to understand life, and death especially. Such searching makes it reasonable to surmise that answers from a deep spiritual connection within them might surface.

Children's wisdom sometimes surprises us because our usual understanding of maturation is the gradual integration of the spiritual into our physical life, when in reality it is our spiritual selves that integrate the physical into our spiritual identity. Hart says it might be more helpful to think of ourselves not as physical beings who may have spiritual experiences, but rather, as spiritual beings that have human experiences – a point also often attributed to Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Hart, along with others, would say that "our entire existence is a spiritual event."

If we lived each day recognizing this identity, how differently we might live in relationship to ourselves and to others and the universe. Our spiritual being is constantly being touched by mysteries that surround us. We see a magnificent sunrise or sunset or something in nature stirs us beyond ourselves, even to tears, and we do not know why. We hold a baby or child close to us, smelling their warm sweetness, and we are taken out of ourselves, again, moved to tears by the mystery of this small being; we suddenly understood something that moved us or were able to let go of a grudge we have carried for years and we do not know how it happened. The spiritual being is alive in us at all times if we are attentive. If we realized this as adults, how differently we would relate to and listen to children and in turn assist them in paying attention to and trusting their inner spiritual connections.

Advertisement

Transformation into wholeness and integration is age-old wisdom described in all the mystics. The process, however, requires attentiveness to reactions, thoughts and feelings — recognizing and claiming our wounds and shadows — those parts of our lives we keep enslaved and that enslave us. It means pulling back those projections onto others of our unwanted shadows and integrating them so we can love them in ourselves and then in our so-called enemies. Transformation and wholeness require discipline, yes, but it is the road to deepening wisdom, love, compassion and true freedom to be wholly ourselves.

Stories of persons known traditionally as mystics, whether poets or saints, reveal that some seem to have deeper access to the connection with the spiritual sea we live in. They probably began as seekers and then, when drawn more deeply by the spiritual, came to understand it is God who is the initiator because as John of the Cross notes in "The Dark Night of the Soul" — "the height of the divine wisdom … exceeds the abilities of the soul." Early childhood visitations and those later on are luring reminders to us of the truth of our potential unless it has been trained out of us.

As I reflected on this mystery of children's spiritual lives, I realized how important it is to know and believe that spiritual sensitivity can be regained even for the deeply wounded. Going back into our memories of childhood, we may well discover those moments of visitation. Turn around, become like children. Let go of the strong, clinging wounds or the ego needs Jesus struggled with in his desert experience — let listening, wonder, pondering, seeking the invisible become part of daily life. Share moments of insight, connection, being loved and cherished by the Spirit with others. And create a new community of spiritual beings. Bring mystical life from the margins to the center of life.