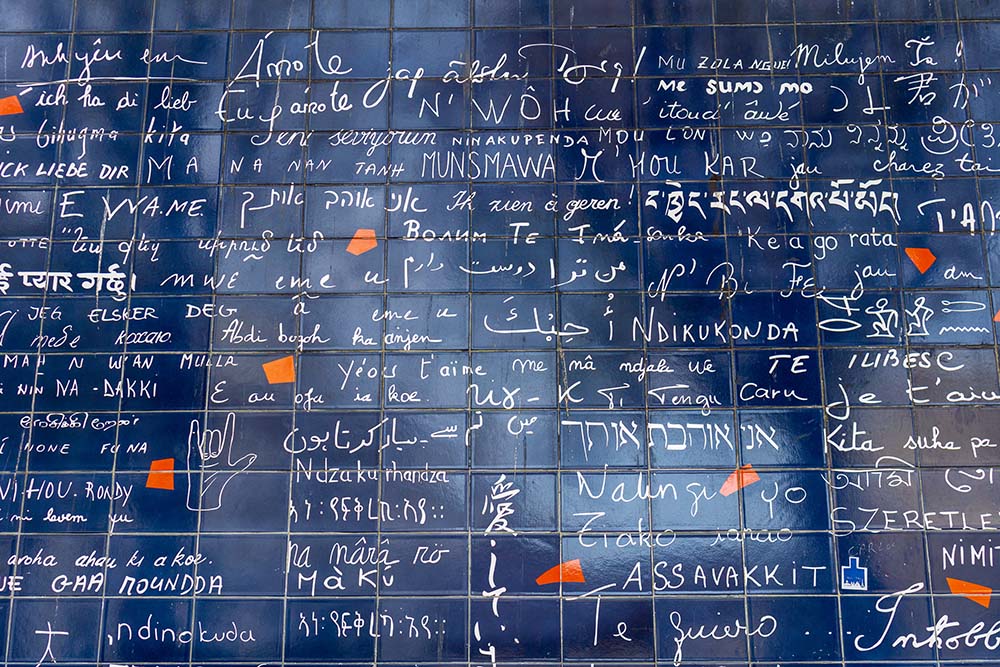

(Wikimedia Commons/Jami430)

For nearly two years now, I've been living in a place where the majority of my day is spent speaking a language that I did not grow up speaking. I have long admired people who can speak multiple languages, and I remember having deep respect for the Sister of Providence who entered the congregation with me and experienced her first three years of formation in the United States while still learning English.

Communication across languages and cultures can be grueling. I have experienced my share of miscommunications and disconnects during the last two years. Each snafu has taught me something.

I'll never forget the moment when I offered to pass my housemate the salad at the dinner table, and she held up her arm with the back of her hand facing me. In my culture, I could only imagine she was threatening to slap me with the back of her hand. "It's only salad!" I thought. On the contrary, in Mexico, this gesture means "No, thank you," which my housemate kindly explained to me when she saw my wide-eyed reaction.

I learned the word blandita when I thought one sister was calling my cooking tasteless, but she only meant to say the meat was juicy. (Although blandita sounds like "bland," it actually means tender.)

One day when I went out with friends and thought I said I'd be home later, my housemate understood me to say, "I'll be right back." This led my housemates to think something awful had happened to me when I did not return until several hours later.

Early on, there were plenty of lonely moments when I sat in silence in our community, too tired to make heads or tails of what my housemates were talking about. I still notice that at times when I am anxious or exhausted, Spanish words just do not flow out of my mouth the way I'd like them to. I admit that sometimes I don't ask what a word means because I'm embarrassed, drained, or simply don't want to interrupt the flow of conversation.

On the flip side, there are times more recently when I find myself thinking in Spanish and cannot grasp how to explain something in English.

During the first phase of my integration into common life in Mexico, I made it my mission to emulate and mimic words and phrases the sisters I live with use. I know a lot of my vocabulary still comes from them, but over time I've started bringing more of myself into my language choices. My housemates have also been intentional about learning English since my arrival, which has brought more mutuality into our communication.

Somehow, the way languages mix both in my head and in my daily life — especially as my Spanish has improved and my housemates learn more English — makes me feel closer to the experience of Pentecost, which we celebrated as a church last weekend. Community life, especially living in an intercultural, intercongregational house, has broken open the meaning of speaking in tongues for me. And it's not just about sounds and spoken words.

I believe that everyone living common life — whether in a family unit, with other vowed community members or any other variety of motley intentional crews — experiences Pentecost. In common life, we face the pain and blessing of interpreting to one another what our words and actions truly mean, and often we are not speaking the same language, either literally or figuratively.

Advertisement

The truth is that even speaking the same dialect and growing up in the same town, we have to reach across differences in communication to find the unity we seek in any form of common life. Miscommunication and confusion will happen. Sometimes it feels like hard work, and sometimes it feels more like the celebration in the Upper Room.

My housemate and I came to this conclusion about the gift and struggle of intercultural common life after a recent house squabble based on differing cultural norms. My cultural leaning toward independence and my housemates' cultural leaning toward dependence meant a decision I had made without consulting my housemates had caused others pain. Although it had not been my intent, the impact was real.

The resulting conversations drew us into a Pentecost moment: We leaned in to understand what we could of one another, moving beyond word choice and accents to understand each other's hearts. I could almost feel the growing pains in my body as we worked through the hurt. It was both hard and good.

Perhaps part of the miracle of what happened in that upper room at Pentecost is just this: the fact that people leaned in to understand what they could of one another. They read body language and context and could feel one another's energy in a way that didn't require words.

I experienced just such a Pentecostal moment last week when I learned that a migrant who had been waiting for asylum in Nogales, Sonora, for over a year would soon be paroled into the U.S. When I saw her at the Kino Border Initiative migrant aid center, I clasped her arm and the words flew out of my mouth: "Next Monday!" Without thinking, I had spoken to her in English, but her response made it clear that she knew exactly what I was talking about. Her tears flowed and my heart swelled.

Maybe speaking in tongues means that the Holy Spirit moves us to accept the pieces we don't understand so as to embrace the essence of another person. Maybe we speak in tongues when we find the goodness in another's eyes, when we can imagine someone who irks us as their vulnerable infant selves, when we stop speaking so an unconventional voice can be heard.

I'm willing to bet the apostles in the Upper Room would agree that speaking in tongues doesn't mean understanding every word that another person says. It's the magic of seeing another person or being fully seen without needing the right words. It happens when we put down our defensiveness and our personal agenda because we want to hear someone else's heart and celebrate who they are.

Like the apostles in the Upper Room, we may not always understand, and sometimes it might take a mighty wind to inspire us. What matters is that we are "all together, in one place" (Acts 2:1), willing to let the Spirit do her work.