Tiny galaxy HIPASS J1131–31 peeks out from behind the glare of star TYC 7215-199-1, a Milky Way star positioned between Hubble and the galaxy in this Dec. 6, 2022, photo. (Courtesy of NASA/ESA/Igor Karachentsev [SAO RAS])

I love science. I love how it's always looking out for those of us who ask more questions than is conducive to a good night's sleep.

How it tells us that Sister Moon — lonely as she looks up there in darkest night — was once a chunk of Mother Earth (although it might do so in higher-falutin' language.)

How it names what's "alive": Life. Animate — with a list of nonnegotiable characteristics. And what's "not alive": in-animate, reverse engineering the same impressive list. And then conscientious science goes on to worry for decades about such slippery terminology and circular logic.

If you catch a scientist outside the lab, fiddling with a rock on the beach for instance, their data get complicated. I once met a Sister of Mercy, trained as a chemist, who admitted to weeping as her colleague washed some of the moon down the sink in their aerospace lab. She was part of a team tasked by NASA to study purloined moon rocks from one of the Apollo missions. Later she took to giving silent retreats on the writings of Teilhard de Chardin, and the sacred fabric of spacetime.

I love how science can stare at each wonder of the world with more and more fabulous eyes and venture novel guesses at how it all works together. I love how science can stand up to what we now call superstition, and yet give credit to the well-meaning explorers who persisted wholeheartedly for centuries before us.

Without the cool toys science has today — mass spectrometers, DNA sequencers, polymerase chain reactors, microchips, macro spyware — curious, sleepless folks the world over made the very best guesses they could about existence itself and other puzzling phenomena.

Yet, thankfully the quest goes asymptotically on and on … with no showstopping certainties in sight.

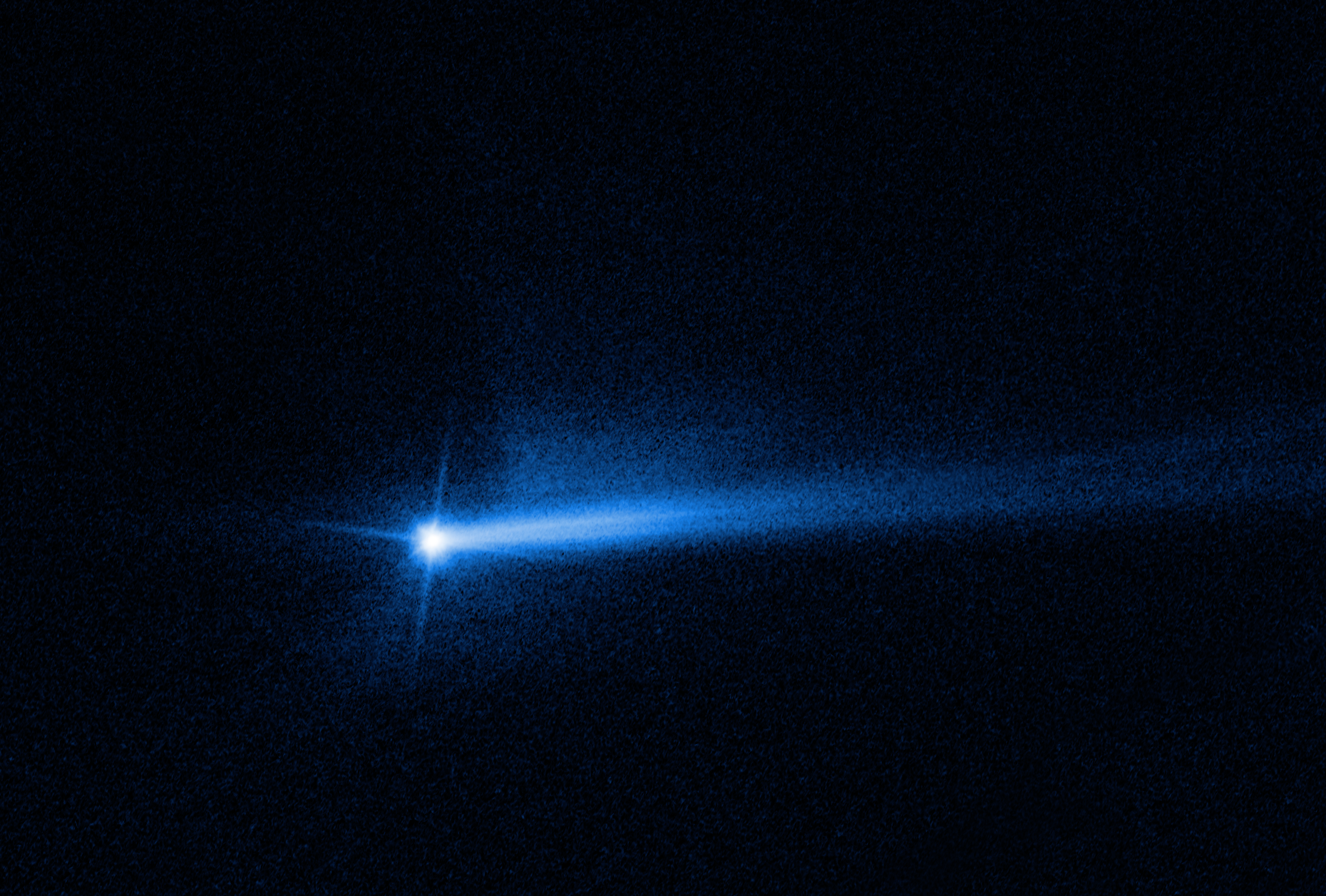

Two tails of dust ejected from the Didymos-Dimorphos asteroid system are seen in this Oct. 20 image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, documenting the lingering aftermath of the Sept. 26 planetary defense test. The spacecraft impacted Dimorphos, a small moonlet of Didymos, to change Dimorphos' orbit by crashing into it. (Courtesy of NASA/ESA/STScI/Jian-Yang Li [PSI])

Since 1990, NASA has been peering into the heavens with the Hubble Space Telescope. More recently through the infrared eyes of the James Webb Space Telescope we are seeing farther back in time, with crisper resolution to enjoy the astral calligraphy of the vast unknown.

Most recently, in September 2022, NASA pulled off an astonishing maneuver 6.7 million miles from home. It knocked an asteroid, a moonlet named Dimorphos, slightly off its orbit around its traveling companion, Didymos. This was merely target practice in case, years from now, we see a real death star heading our way. It seems like a lot of fuss and funding over two benign enough celestial passersby.

Perhaps science still feels sorry for the dinosaurs who didn’t see the big one coming 65 million years ago. Or maybe science just decides to do stuff to see if it can.

There was another kind of target practice going on as I wrote this. At COP27 — near biblically historic Mount Sinai in Egypt — 200 countries, with their heads in the same room, had just wrapped up efforts to locate our common global heart, in hopes of reckoning with the death star that's already hit us: the rapidly changing climate and its disparate effects on earthly life.

How many degrees of global fever can humans sweat out? How will nations help each other cope? Who will compensate for the loss and damage already done? Who can afford not to?

As United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned in his COP27 closing statement: " … we cannot wait for a miracle from a mountaintop."

Speaking of mountains, I hope they were invited to the U.N. Biodiversity Convention (COP15), immediately following COP27. Were there seats at the table for the melting Alps and Andes, the ravaged Appalachians? I hope the oak trees were invited, too, and the carbon-sequestering wetlands; and the gossiping "wood-wide web" of mycorrhizal fungi; the migratory Arctic terns. And of course, the insects — every enigmatic, pesky one. We could use the wisdom of these planetary elders on energy security, and waste management; how to navigate, and orchestrate communal life. Hints on Earthly Etiquette in general. There is so much to learn.

A waxing crescent moon is photographed from the International Space Station during an orbital sunset as the station flies 268 miles above the Pacific Ocean, east of New Zealand. (Courtesy of NASA)

Fastidious scientists come to the table imagining that if we all knew the facts, we would take action. Climate info-graphs and predictive charts paper the walls and ceilings of our corporate board rooms, educational institutions, and solitary consciences.

While speaking about her recent book, How Art Can Help Defend the Natural World: Encouragement for Earth’s Weary Lovers, Kathleen Dean Moore said: "If people only felt the beauty and goodness of what is being taken from them, they would act."

If we only knew, if we only felt, if we could only see — as God sees — both up close and far away. All of it good, alive and busy becoming whole. Seems the crisis we have is a crisis of vision, and mis-engaged imagination.

Walk with me into an old growth forest. What do you see, smell, hear?

Who would imagine seeing rolls of toilet tissue and colored toothpicks stacked perpendicular to the sky? What of the furry and feathered forest folk, the lady slipper orchids, and the dryads? How can we delight like lovers yet act as loggers?

Walk with me by the full moonlit ocean, glistening and gravid with salty life.

Imagine thinking of a dump to trash our plastics? What of the whales and walruses, ancient clusters of lustrous corals, and the mermaids scratching their innocent heads?

Listen. Who’s weeping as such goodness and beauty washes down the drain? Truly, more and more of us. Listen.

Think with me — about violence. What's at the heart of every violent act if not the squandering of our critical human attention on narrow and narrower concerns?

We humans have so many species-specific grievances for the Creator-in-Chief right now. Some of us seem to have gotten the wrong bodies; some the wrong-colored skins. Some of us feel labeled as “abled" o “disabled,” in a variety of unappreciated ways. Our neighbors are not as lovable as ourselves. Oops!

Plus, this planet's not quite right. Rivers are crooked, mountains hide metals we need. Wetlands! Such a waste of valuable space. And then there's all that extra-terrestrial clutter above— disorderly stardust — just looking down at us funny — likely up to no good.

Advertisement

We're thinking of moving to the moon, or Mars. But what to pack? We don't even know what we need down here. Or how to get it without depriving others. And which others shall we leave behind? Who can we afford to be without?

Wait. Doesn't the psalmist tell us we’re all “fearfully and wonderfully made?" (Psalm 139:13-14). Doesn't the very heart's truth of science say so? And every spiritual tradition — in multi-lingual eloquence? Wonder-full — just as we are. Here, of Earth — just as she is.

Of course, we can keep on trying to second guess our genes, choose our favorite hormones, facelift Mother Earth, and rearrange the sky.

Because we can.

But what if our uniquely human virtuosity lies in looking, learning, seeking to conspire with this gratuitous flow of beauty and goodness — praising as we go?