Sisters of Life pray at Mass. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Life)

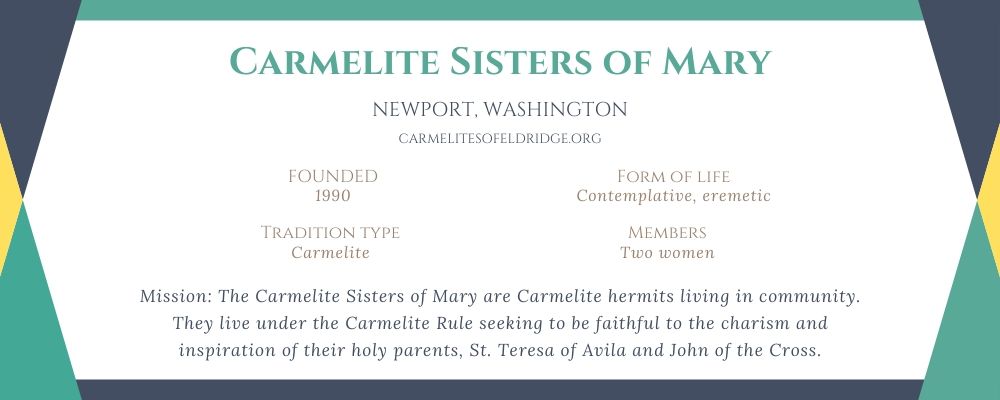

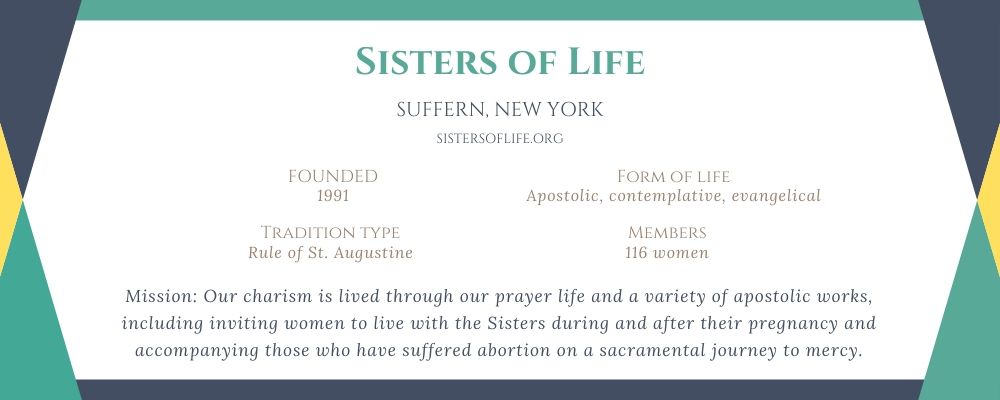

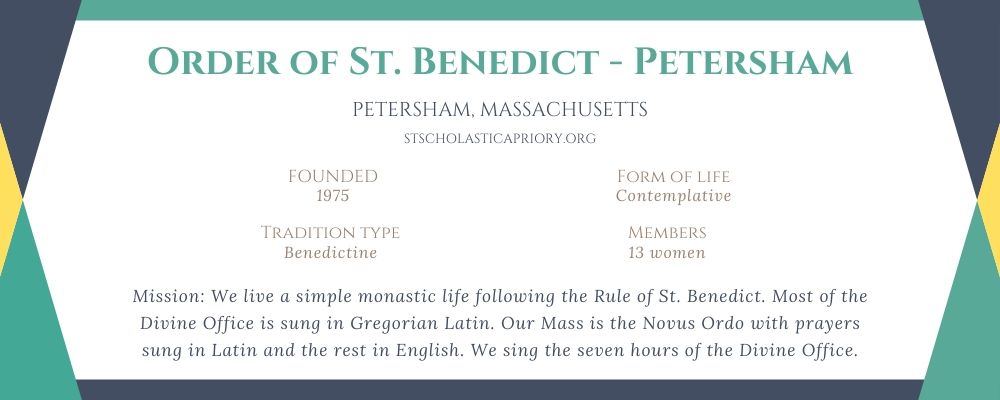

Editor's note: This story is part of a four-part series on religious communities that have been created since 1965, the year the Second Vatican Council ended. The emerging communities come from the third edition of a 2017 directory, "Emerging U.S. Communities of Consecrated Life Since Vatican II." This part explores three religious institutes. Read the rest of the series here.

The day is cold, but the sun is shining through the towering tamaracks and pines on the side of the mountain called Regina de Cor Carmeli, or Queen, Beauty of Carmel.

A statue of St. Teresa of Avila stands in the snow outside the community building at the Carmelite Sisters of Mary on Jan. 30 in Newport, Washington. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

About 4 feet of snow has fallen so far, but most of it has melted in the last week, so the steep, rocky driveway to the Carmelite Sisters of Mary is passable again. At the top is a cluster of hermitages and a community building that houses the central chapel, marked by a copper statue of St. Teresa of Avila, who looks out over the boulders and trees and the many hiking paths that wind through them.

Inside, a little wood stove blazes as Sr. Leslie Lund talks about how she loved her life with the Carmelite Sisters of Indianapolis. But the busy convent life seemed anathema to the life she knew Carmelite sisters were also called to — that of a hermit.

The community was shrinking quickly, and there were no new vocations to sustain it. In the late 1980s, it seemed to Lund that all of her peers had left, and she transferred to the Carmelite community in Barrington, Rhode Island. There, she met Sr. Nancy Casale and began having a series of dreams about hermit life.

At the same time, Casale kept learning more about St. Teresa's views on living among the people rather than behind a convent's walls. She was also troubled that instead of living with people who live in poverty, the convent was in one of the most affluent areas of the United States.

Eventually, the two set out to drive across the country, not knowing where they would end up. Lund had grown up in Spokane, Washington, and Casale's family was in California. They thought they might find a place to live out their calling somewhere in between.

But when they got to Spokane in 1990, everything fell into place. Bishop William Skylstad, Spokane's bishop at the time, welcomed them to the diocese. The parish they went to for Mass had a huge stained-glass window of St. Teresa of Avila, foundress of the Carmelite order. Within two weeks of arriving, they found an 80-acre site in the mountains about 45 minutes north of Spokane that would allow them to both live among people who live in poverty and have the solitude they needed for a hermetic life. Donations allowed them to buy the land.

Advertisement

Casale compared leaving her former community to facing death.

"It was so wrenching because it was everything I had wanted in my life," she said.

But the community remains close, Lund said, and about half of her former sisters have visited.

By 1993, Skylstad declared the Carmelite Sisters of Mary an official religious institute, defined as a community whose members make public vows. It is one of 159 communities included in the 2017 directory of emerging communities published by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University that lists religious communities formed in the United States since the end of the Second Vatican Council.

"Teresa wanted her nuns to be not only nuns, but hermits. When we came here, we really wanted it to be like the original life on Mount Carmel was," Lund said. "Our dream would have been to have this place filled with permanent hermits."

Sr. Leslie Lund speaks Jan. 30 about the founding of the Carmelite Sisters of Mary in Newport, Washington. Founders Lund and Sr. Nancy Casale are the only remaining members of the order. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

But while many have come, most have stayed only months or a few years, and Lund and Casale — both in their 70s — are all that remain.

But looking back over their 30 years here, Lund and Casale said they have no regrets.

"We've never been healers for people. We allow them the space for solitude that allows them to discern where they're going next in their life," Lund said. "Transition — that's what God, in the end, made this place. A place of transition and healing."

Neither could have foreseen the transitions in their own lives. Casale, a former ballet dancer, is now a chainsaw-toting forester. Lund is an author, a respected speaker on St. Teresa and prayer, and in charge of driving the tractor to clear the road, drag fallen trees and complete other tasks on the rugged terrain.

The land had been logged off several times before the sisters arrived, Casale said, so the timber must be managed rather than simply protected. Her work has paid off: In 2003, the land was named the state's wildlife habitat farm of the year.

Donations seem to come just when they're needed, such as a Catholic carpenter who forgave the sisters' debt for building their hermitages or the Knights of Columbus repairing their truck, Sweet Chariot.

There was no electricity or running water for the sisters' first two years on their land. They relied on an outhouse, a wood stove and oil lamps.

Sr. Nancy Casale talks about the importance of solitude for the Carmelite Sisters of Mary on Jan. 30 in Newport, Washington. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

But the solitude, they say, was worth it. The Carmelite Sisters of Mary say it is essential to finding intimacy with God.

"There's a big difference between being alone and being lonely," Casale said. "Being alone is very full. It heightens my awareness, attunes me to what I'm hearing and what I'm seeing. What I'm feeling with loneliness is pain. It's an emptiness. It's a fearsome emptiness."

Casale said fear of loneliness keeps people from the solitude they need to discover what is happening inside them.

"I've found it one of the biggest helps to my spiritual journey. For me, it was like dancing. The barre exercises were so difficult, but if you can do them, the freedom that comes at the end — I don't know anything more exhilarating," Casale said. "I'll never fathom the richness of solitude, the depth it opens up to me."

Solitude is necessary, Lund said, because God is subtle.

"God is mainly silence and solitude. That's where you find God," Lund said. "You make yourself available. Carmelites do pray the Office, but their private prayer is mainly listening to God."

'I am a gift'

The Sisters of Life believe that if people would listen to God, they would transform society.

Sisters of Life share a meal. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Life)

"I think the person as gift is really revolutionary," said Sister Marie Veritas, director of evangelization for the Sisters of Life. "You just wish everyone could know first their own dignity, know that 'I am a gift, that's who I am.' If everyone knew that, they could see others as a gift."

And when you see each life as a gift, lives can no longer become disposable.

Sister Marie Veritas said people often come to the community with preconceived notions of what the sisters are and what they do, but come away surprised. The community has grown dramatically since its founding in 1991 and now has 116 sisters and 49 in formation.

"The heartbeat of our community is the beauty and dignity of the human person, made in the image of God," she said. "We're contemplative-actives, so our first work is prayer. Four and a half hours are spent in prayer every day."

She said while Sisters of Life pray outside abortion clinics a few times a year, that is far from their focus.

"Our main ministry is serving women who are pregnant and in crisis and to give hope and healing after abortion," Sister Marie Veritas said. "It's about the mercy and healing of Jesus."

The community, based in Suffern, New York, about an hour northwest of Manhattan, operates the Holy Respite Mission, a convent where pregnant women are invited to live with the sisters during and after their pregnancies.

A Sister of Life talks to a mother and baby. The Sisters of Life invite pregnant women to live with them at their convent during their pregnancies. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Life)

The convent also hosts a phone ministry that annually serves more than 700 pregnant women; an international retreat center; and a library. They also accompany those who have had abortions on a journey to mercy, evangelize the culture of life, and staff the New York Archdiocese's Family Life Office and Respect Life Office.

Sister Marie Veritas said the community's focus on prayer comes from founder Cardinal John O'Connor's realization in 1975 that society's deep crisis of faith could "only be cast out by prayer and fasting," like the demon cast out by Jesus in Mark 9.

‘You’re more Benedictine than we are’

The Order of St. Benedict-Petersham, a community of 13 Benedictine sisters in Massachusetts, was founded in 1975 but has roots in a Catholic student center at Harvard University in the 1940s.

Mother Mary Elizabeth Kloss, the order's prioress, said that faith group persevered until the 1970s, when several of the women went a step further and formed a small Benedictine community. In 1979, they connected with the Benedictines at Stanbrook Abbey in England, and by 1984, they had become a religious institute. A year later, they moved from the Boston area to Petersham in bucolic central Massachusetts, where they have a small monastery on 200 wooded acres surrounded by 10,000 acres of conservation land, including a state forest.

A Petersham Benedictine sister enjoys a walk with a monk of St. Mary's Monastery, which shares the sisters' campus. (Courtesy of the Order of St. Benedict-Petersham)

Sharing the campus is St. Mary's Monastery, a community of Benedictine men. While the orders are separate, they hold Mass and pray the Divine Office at the same time each day.

The sisters once ran a small publishing house and then a small bakery, but both caused too much disruption in their contemplative life, which requires seven hours of praying the Divine Office, most of it in Gregorian chant.

Now, the 13 sisters hope to open a creamery to make cheese, but they need one or two more sisters. Unlike baked goods, cheese has a long shelf life and doesn't require the same daily commitment bread does.

Petersham Benedictines pray at St. Scholastica Priory in Petersham, Massachusetts. (Courtesy of the Order of St. Benedict-Petersham)

"The sisters here make fantastic cheese," Kloss said.

Kloss, who entered in 1985, said the founders never questioned whether they would be Benedictines.

"The Benedictine Rule was very familiar to the community. They were already doing some of the Divine Office," she said. "As Benedictine monks and abbots were coming to see us, they were saying, 'You're more Benedictine than we are.' "

Source: "Emerging U.S. Communities of Consecrated Life Since Vatican II," Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University (GSR graphic / Pam Hackenmiller)

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is dstockman@ncronline.org. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]