(Unsplash/Jens Lelie)

As a person about to move out of a house I've lived in for nine years, I have some thoughts about packing and unpacking. First, a lot of what I'm dealing with today came with me from my last move. And where those items — some still boxed — came from still clutter the trail of my journey from previous there(s) to here.

This makes me think about habits, and the burden of hauling stuff that no longer serves, let alone inspires. Sadly, often cherished ideas fall into this category, although they're even harder to bid adieu than that pretty silk dress Mother gave me, with its tags still pinned to the sleeve. And she's been dead for 20 years.

And how much stuff travels with us because we just don't know how to dispose of it? For dead bodies we have rituals. There are recycling posters that tell us how to sort plastics from paper.

As a creative people, we've made things that we'd best be letting go of … but how? We know by now, having circumnavigated and populated the globe, that there is no place called "Away" to throw stuff ... be it plastic bottles, obsolete tech devices, nuclear waste or beliefs that have overstayed their welcome.

In addition to toxic stuff, we have accumulated some very self-serving habits. The planet needs the same imagination we used to devise them to pause and reinvent the wheel that is currently spinning out of control in its own ideological rut. Certain ideas and unexamined ways of being might rightly require their own recycling bins.

But I didn't come here to grumble about stuff — profound or trivial. I came to think about violence — gun violence and manmade weapons in general.

Think with me about violence. What is at the heart of every violent act, if not the squandering of our precious human attention on narrow and narrower concerns, on smaller and smaller pronouns: mine, me, I? Requiring deadlier defenses to protect an illusion perpetrated by the meanest, most primitive parts of ourselves, which we weaponize, with ever fancier superhuman ingenuity.

"Guns." Hmm … "snug," backwards.

As a way of keeping us alert on long road trips, my father taught us to read billboards and street signs backwards — a skill of ineffable value — still useful in long supermarket checkout lanes.

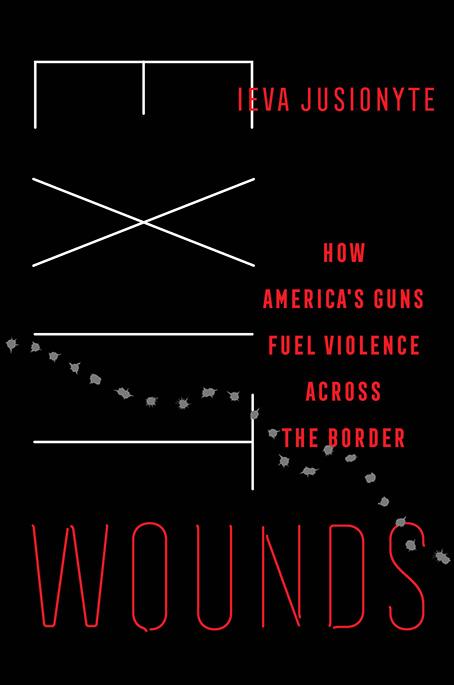

Book cover to Exit Wounds by Ieva Jusionyte

I'm reading a very disturbing book, Exit Wounds: How America's Guns Fuel Violence Across the Border. The dust jacket is black; the title is split — "EXIT" printed down along the spine; "WOUNDS" along the bottom and the author's name, Ieva Jusionyte, at the top, spelt in blood red ink. Piercing the paper cover are tiny star bursts — as is the shape, the author (a former paramedic) informs us, of the hole a bullet makes as it exits the flesh of its victim.

Ieva Jusionyte had watched the movement of guns and illegal drugs across the border between the United States and Mexico. As an anthropologist, she noticed patterns; drugs were moving north; guns were moving south. Questions arose. Who was using those guns? Could it be the drug smugglers to protect the clandestine routes they traveled to deliver their goods to anxious customers in the U.S.? Yes, she verifies.

Questions keep arising: Why do we need the drugs and the guns? What are the underlying causes that produce these addictions to power and poison in the first place? Such enormous and complex questions! I lift my eyes from my notebook and look out the window.

I watch an osprey circle the lake. He goes high for the broadest view — the biggest picture — the most comprehensive scan for a possible catch. He can only catch one fish at a time, so he collapses his spacious gyre. Then feet first, it takes his whole body, often fully submerged. Once he is underwater, I imagine his effort to rise up with soaked wings and one trout heavier, slightly drunk from the dunk, yet sure of his way home to his hatchlings' wide-open mouths, hungry in their nest.

Questions galore: Firstborn son of first parents — Cain — kills his brother, Abel. What more do we need to know about what we are capable of? What provoked the first murder? What made violence an option just outside the closed shut gates of Eden?

Now two swans are out there on the lake. The ripples from the osprey's breakfast plunge have reached either shore, been absorbed by the peaceful greenery on the banks. The swans are upside down, poking their graceful necks at the mud on the bottom where slimy delicacies grow.

Snug. Sort of a silly word. What it lacks in sleek elegance it gains in poetic accuracy. Safe, coddled, blind. Bullet is another loaded word. Many of us have searched for alternatives to "bullet points" to use in PowerPoint presentations. I tried using a peace dove emoji in a previous column here, but the editors said it was too gimmicky … couldn't use hearts or flowers either.

So when alternatives cannot be imagined or are denied us, to what do we resort? What were Cain's options before self-help books and support groups, or Freud? Didn't God write brotherly love in Cain's heart? Or did we have to wait for Jesus to post that text?

Why aren't the swans and the ospreys buying drugs and using weapons?

If these seem like silly questions, try coming up with a serious answer. We are in need of reasonable answers these days. Ask the beasts. Ask the victims of violence. Ask the perpetrators. Ask yourself.

How does "snug" feel backwards?

Advertisement

One more thought before I close. We, women and men of mercy and justice, think of ourselves as nonviolent. Who among us would raise a fist or a weapon to another with the intent to harm or kill? But what if we expand the meaning of the word "another" to include beings other than humans? To include oceans, air, soil, microbes, and all living beings who hold earthly life as dear and precariously as we do?

Should we be "unpacking" stuff we never thought of as weapons before? Should we be labeling plastic water bottles as weapons of mass destruction? What if we asked the oceans — the ultimate cradle of all the unborn — about plastics? And the phytoplankton, who feed the krill, who feed the small fish, who feed everyone right on up the food chain — to ourselves and our families and the generations of all life to come?

What if we asked the air how to label the fossil fuel-fed lawnmowers, leaf blowers, and sidewalk edgers? And what would the soil and our tiny kin who live there say about pesticides and fertilizers aimed directly at them?

Are we so snug in our identity as nonviolent people that we cannot see that no one lives harmlessly — not ospreys or swans or us? But we are capable of choosing where we aim, capable of laying down our savage arms, and unpacking unexamined ideas and lethal words that create victims and enemies of our earthly family.

Is paradise the place where enough is enough?

Where the only weapons we pack are seeds of union and charity — the words loaded in our hearts — our hearts at home, always and at last, in the body of Christ, forever-present and pierced by stars.