Left: St. Hildegard of Bingen depicted in stained glass in Koblenz, Germany (Wikimedia Commons/Thomas Hummel). Right: St. Teresa of Ávila depicted in stained glass in Ávila, Spain (Wikimedia Commons/Dennis Jarvis). Background photo: A view of the Basilica of Our Lady of the Mount in Bandra, Mumbai, India (Wikimedia Commons/Rakesh).

Last year, I was preparing to give a recollection to some communities of sisters in the Conference of Religious India's local unit. The challenge before me was that I didn't yet know all the participants personally, but I was sure they would be a mixed group with progressive and conservative leanings (somewhat like members of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious in the United States).

On that occasion, both were called to work together in synodality and all that it implies.

I had to try to get two giggles with one tickle in this era of multitasking. Hence, to resolve my dilemma, I decided to speak about prayer with St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) and St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-82).

Not surprisingly, one of them had a progressive inclination to reform whereas the other a relatively conservative outlook. However, both were called to respond to the signs and needs of their times, and both were proclaimed doctors of the church.

Women mystics of the Middle Ages have often captured my attention with their bold, somewhat strange and amusing ways of getting away with challenging the status quo of their times. They seemed full of zeal to reform the church from moral corruption and laxity in the living of the faith. When I come across their biographies, I'm enthralled with the depth and breadth of their wisdom, insight and creativity.

Moreover, reading them offers an experience, like watching movies with digitally inserted visions and voices of heavenly personalities, accompanied by private revelations and a call to respond to a crisis in the church or society.

Several women mystics with little formal education have left us dictations or writings that were initially subjected to scrutiny and enlisted in the Index of Forbidden Books. However, as it happens today, negative publicity helped in disseminating their prophetic teachings even more. A few manuscripts were read or heard and approved by the pope himself for publication, though!

Advertisement

I often wonder why there seems to be a common pattern in the sequence of events connected to the call experienced by these women. Did biographers cut or embellish their life stories to hasten the process of approval of their teachings as well as their canonization? Did God use the mystics' or biographers' creative visualization to give a message to the people?

Nevertheless, what splendid witness was offered to the union of mystics with Jesus Christ in his passion, death and resurrection!

Whether during the lifetime of these individuals or after their death, critics were converted into followers. Some of these prophetic women found their way into the lists of saints and doctors of the church because of their perennial teachings, irrespective of whether they had progressive or conservative keys to reform.

What was their secret? Do women reformers today also have unique gifts that could help the church in all times and contexts, irrespective of their ideological leanings?

Over the centuries, the Catholic Church has responded to various challenges, especially through its councils and documents, which seem to counter each other from one era to another. The Council of Trent and the Second Vatican Council are excellent examples of conservative and progressive keys to reform. Weren't they relevant for their own times? Then why do we find ideological polarization in the church so disconcerting today?

Social media and digital technologies have stirred the laity to either think for themselves or follow ideological leaders indiscriminately. The same seems to be happening in consecrated life.

A group is considered conservative if it gives greater importance to purity and loyalty to one's authority, tradition and closed circle. It looks for stability and security in the familiar. Another with opposite characteristics is said to be progressive. Both groups try to cancel each other.

I am not sure whether ideological polarization within the same era was so obvious in the past as it is today. The church cannot apply the same perspective to all contexts and pastoral concerns. It needs to discern what stand the Holy Spirit wants it to take in resolving major controversies.

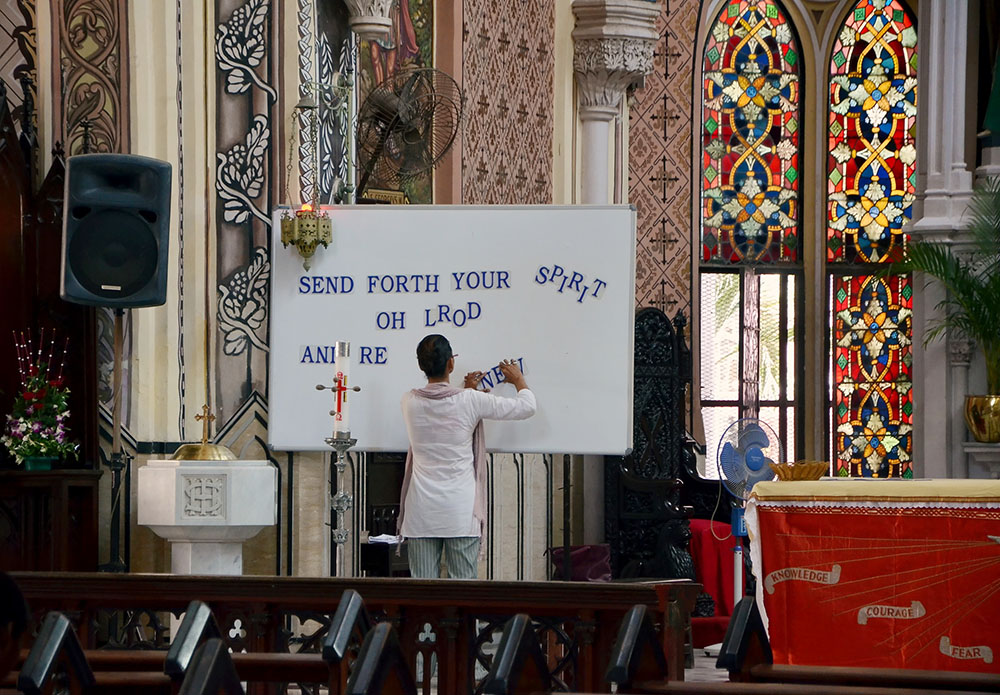

A young woman arranges a sign in the Catholic cathedral of Mumbai, India. (Dreamstime/Svglass)

Though we are invited to be innovative when responding to new questions, it would be unwise to discard the wisdom gained by the church of Jesus Christ, as a whole, during its journey over the millennia.

Today, the world is shaken up by disclosures of sexual abuse by clergy and its cover-up. Many among the hierarchy have ignored or harassed victims by merely transferring abusers from one parish, diocese or continent to another. No wonder some people in other religions say that Christianity is another word for hypocrisy. Our religion is not merely a system of ethics, but it is also not supposed to be unethical!

Twenty years ago, I remember a priest giving a talk to a group in which he said if a man in the West raped a woman, it was treated at the same level as not paying his taxes! He relativized chastity by saying it should not be taken seriously. Similarly, there are church leaders who treat sexual abuse and liturgical abuse the same way. They refuse to accept that the former is a crime against human dignity and can never be justified.

Does it matter whether such religious leaders are progressive or conservative? They are all patriarchal, sexist and misogynist!

I am led to reflect upon the life of Hildegard of Bingen, who emerged as a Benedictine nun and prophetess in the 12th-century context of the Crusades. Due to pastoral neglect as well as other kinds of corruption among the clergy, the laity were attracted to so-called heretical movements, such as the Cathars. The mystic pushed the pope and his council to reform lukewarm and lax clerics.

She became popular among the people. Hence, although a progressive herself, she was proclaimed "doctor of the church" by Benedict XVI, a conservative pope.

On the other hand, Teresa of Ávila lived as a Carmelite nun in the 16th century context of the Counter Reformation. In the lax milieu of her monastery, she had a conversion experience pushing her to reform the Carmelite orders of men as well as women. She founded Discalced Carmelite monasteries with a strict observance.

Despite her conservative key to reform, she was proclaimed the first woman doctor of the church by Paul VI, a progressive pope who led the Second Vatican Council.

Both these women mystics worked for reform in contexts of moral corruption and laxity. Their teachings on prayer and other topics are relevant for all times. Aren't God's ways beyond our imagination? As the church is moving toward greater synodality, all its members need to rise above their progressive or conservative ideologies and overcome the crises of our times by discerning what the Holy Spirit is saying.

In the final analysis, the church needs women mystics in every era, with perennial teachings, if it truly wants to reform itself!