Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio gives a lecture on Thomas Merton and his epiphany in 1958 at a street corner in Louisville, Kentucky, Nov. 14 at the Center for the Study of Spirituality at St. Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana. (Alecia Westmorland)

Spiritual scholars know well the transcendent tale of Thomas Merton's Fourth-and-Walnut breakthrough.

While running some banal errands in Louisville, Kentucky, on an otherwise unexceptional day in 1958, Merton — a Trappist monk and spiritual writer — experienced a sublime epiphany on the corner of Fourth and Walnut streets.

He recognized a euphoric solidarity with all humankind, later describing that "I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another."

Among the most famous revelations in religious history, the impact of Merton's discovery still reverberates today, said Sr. Ilia Delio, a leading theologian and Franciscan Sister of Washington, D.C., during a Nov. 14 lecture at the Center for the Study of Spirituality at St. Mary's College in Notre Dame, Indiana.

"I call this Merton's big bang," said Delio, who holds multiple degrees in the fields of science and religion and has authored over 20 books. "It was almost like the start of a whole new trajectory of life."

In the inaugural "Fourth and Walnut Lecture," co-sponsored by the International Thomas Merton Society, Delio explored many profound facets of Merton's discovery.

Not only did his words align with the writings of other revered philosophers and thinkers, she noted, but they also reflect a new global shift in spirituality today.

"These experiences put him in an ultimate reality, an experience of underlying reality or wholeness that represents a widening of consciousness, to the cosmos itself," she said.

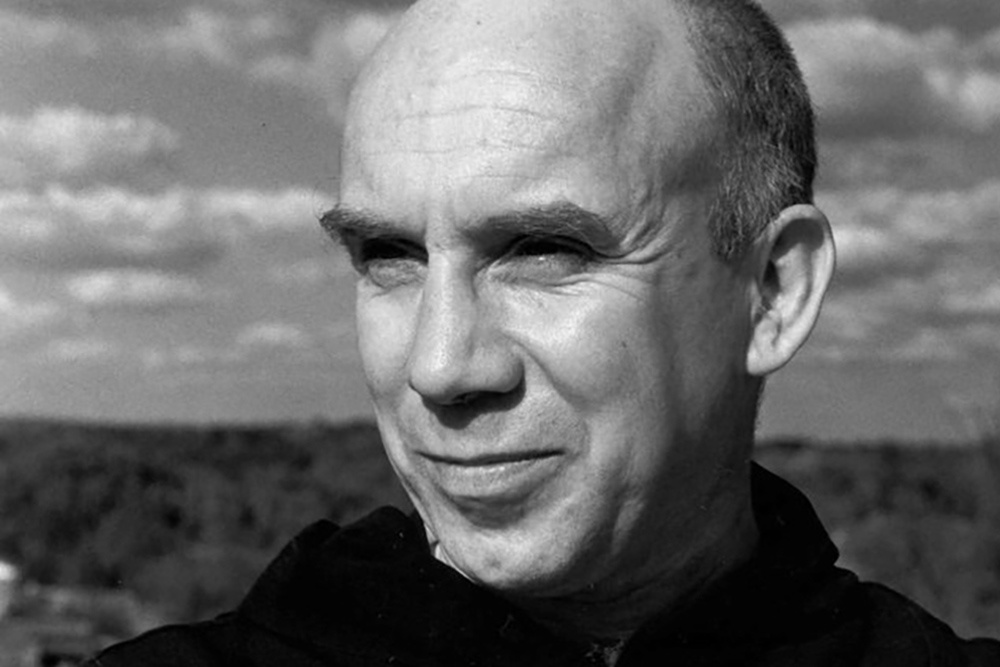

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in an undated photo (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Before his famous revelation, Merton's early spiritual approach took a starkly different perspective, in seeking divine discovery through strict, monastic isolation.

His early writings on grappling with his inner self in solitude — which inspired Delio's own years of monastic living — actually mirror psychiatrist Carl Jung's philosophies of finding "the fullness of life" at the "heart of our own life," Delio said.

"What Jung helped me realize in understanding Thomas Merton is that this notion of individuation, which I think monastic life is, in its best form, is about this: It's about coming home to oneself," she said.

But his earth-shaking discovery at Fourth and Walnut led to a full "mutation" of Merton's secluded approach, she said, to instead focus on the interconnectedness of life and a collective identity.

"He remained in the system of monasticism, and at the same time, something changed in the pattern of that system," she said. "Merton came to see that the entire purpose of monastic life is to realize our underlying oneness, our unity — a hidden wholeness."

Merton's spiritual awakening, Delio said, parallels a concept floated by Catholic theologian Raimon Panikkar, called Christophany.

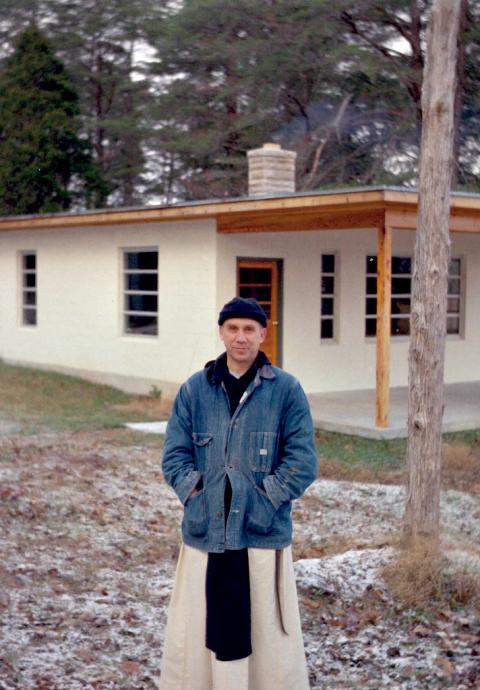

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in an updated photo at the hermitage at Gethsemani Abbey (CNS/Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

She described Christophany as "in a sense, a coming to awareness of the presence of God within me," with each person bearing "the mystery of Christ within."

While this idea stems from Christian Scriptures, Delio emphasized, Panikkar posited that this "Christophanic center" applies to all humans, regardless of their religion. She likened this to Merton's findings, and dubbed his deepening level of awareness as a "Christ consciousness."

"[This] divinity at the heart of our humanity is very relevant to Thomas Merton's own trajectory," Delio said.

Merton's spiritual evolution also led him to conclusions surprisingly similar to those of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Jesuit priest and philosopher, even though their opinions sometimes diverged.

"They looked from two different directions, but in the same direction," Delio said.

The two found common ground in merging science and religion, for instance. Both praised the "holiness of matter," she said, an acknowledgment that humans are composed of matter, and that from this matter comes consciousness allowing the very contemplation of God.

Teilhard even lauded how God is found in matter itself, overlapping Merton's embrace of the interconnectedness of all things.

"I call this Merton waking up to matter," she says. "Coming home to who he was [meant] coming home to what the world is."

The two also shared the idea of God as the embodiment of love. Instead of seeing God as a separate entity who loved humanity, Delio said, Teilhard viewed that "God is love. Love is the very nature of God."

This pairs with Merton's findings that "love is our true destiny," she added, and "we don't find meaning of life by ourselves alone, we find it with another."

Advertisement

They even shared criticisms of the Christian religion as being "too aloof from the world," and focusing too strongly on a spiritual realm "which has nothing to do with the present one," Delio said.

"This kind of mentality is resurfacing today, this kind of, 'The church should not be involved in worldly affairs,' " she noted. "That's why we have a little bit of a divided church."

Merton's Fourth-and-Walnut epiphany even offers insight into society's shifting approach to spirituality today, Delio said, emerging as a Second Axial Age.

The First Axial Age, she explained, refers to the historic period from roughly 900 to 200 B.C. that gave rise to world religions such as Judaism, Buddhism and Hinduism — largely replacing the former tribal and "earth-centered" spiritualities.

The spiritual movements of this era placed focus on humans as autonomous, not being bound to the Earth and with a perspective of "there's a divine nature beyond me," she said.

But the modern era has birthed a Second Axial Age in which "we are moving away from characteristics of the First Axial Age to one of relatedness, immanence, ecology and a global consciousness," Delio said.

She sees Merton representing both Axial eras, as the first gave rise to monasticism, but the second more closely aligns with his 1958 revelation.

Merton also tread in an additional direction that people today can emulate, Delio noted, in his travels to the East to study Buddhism. In a furthering of his "mutational" evolution, he promoted interreligious dialogue and pursued a "transcultural consciousness," she said.

This spiritual unity is "Christophany at its best," she added. "It's to live in the appearance of divine love within every person. As Thomas Merton wrote, 'We must contain all divided worlds in ourselves and transcend in them in Christ.' "

Bearing all this in mind, Delio hails both Merton and Teilhard as "authentically Christian," she said.

"They saw this love of God deeply present in the whole of life in every person," she said. "They made every effort to actualize that love and bring it into existence, where we're no longer aliens to each other, but working together for a new wholeness, a new Earth."