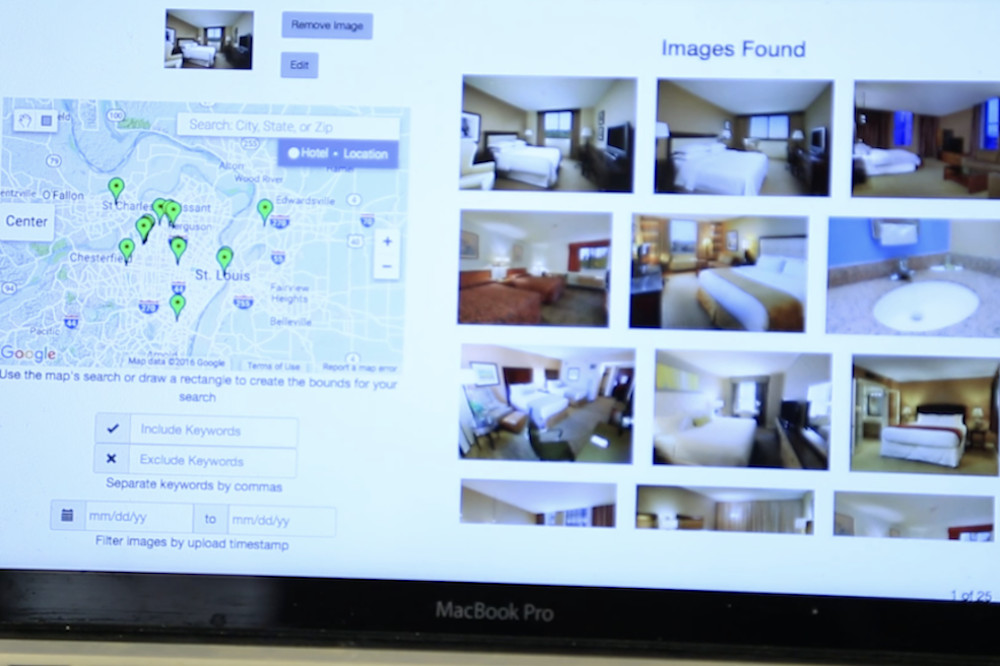

The TraffickCam system uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to compare photos of human trafficking victims to millions of photos of hotel rooms to find where the photo was taken. (Photo provided by Washington University)

It began with a request from the Sisters of St. Joseph Federation, who wanted to ensure their 2008 national gathering was at a hotel that worked to stop human trafficking.

Kimberly Ritter, senior account manager at Nix Conference & Meeting Management, laughed at the idea. "I said, 'Well, we're not in India, Sister.' "

But the sister explained that human trafficking happens everywhere, even in the United States, and at rates that would shock most people: The U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline reports 10,360 cases of identified trafficking in 2021 involving nearly 17,000 victims.

"Then we researched the details and found that the average age of entry into sex trafficking is 12 to 13, and [Nix owner] Molly Hackett and I both had daughters that age. We couldn't believe it," Ritter said. "And it's happening in hotels, where we spend millions of the sisters' money. We knew we had to do something."

So the St. Louis-based Nix worked with the hotel hosting the Sisters of St. Joseph Federation to sign ECPAT-USA's Code of Conduct for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation in Travel and Tourism, a voluntary set of business principles that travel and tour companies can implement to prevent sexual exploitation and trafficking of children.

Nix employees then wondered why they should stop with just one hotel, since they have the buying power to demand every hotel they contract with sign the code of conduct. In 2012, Nix became the first non-hotel company to adopt the code.

At the time, Backpage.com was notorious for running advertisements selling sex, and many ads featured women and girls who had been trafficked. Nix employees, who see hundreds of hotels every year, found they could identify the locations of those women and girls based on the pictures that Backpage.com posted with these ads. But when there were photos of hotels they didn't recognize, "we realized an office of meeting planners wasn't enough," Ritter said.

In 2013, Nix created a new corporation, the Exchange Initiative, to handle its anti-trafficking work, and the company drew the attention of Abby Stylianou, then a graduate student in computer vision and machine learning at Washington University in St. Louis. Stylianou believed computers could use artificial intelligence to recognize similarities in photos to find matches.

Kimberly Ritter (Courtesy of Nix Conference & Meeting Management)

The employees at Nix are "hotel super-recognizers," said Stylianou, now an assistant professor of computer science at St. Louis University. "They're amazing. But the scale that's needed, you have to use computers."

Stylianou collected millions of photos of hotel rooms around the world from travel websites, but the photos of sex-trafficking victims don't look like glossy advertising photos.

With an initial grant from the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, Nix created the free TraffickCam app, which lets users take photos of any hotel room and anonymously submit them to the database. About 600,000 photos have been submitted since it launched in 2016, and hundreds more are submitted every day. Today, the database includes 12 million images of about 500,000 hotels around the world.

"The submitted photos are key because they look more like the victim images," which don't use professional techniques and lighting, Stylianou said.

"The pictures we get the most correct hits on are the ones the public takes," Ritter said. "We need as many pictures as we can possibly get because at 3 p.m. when the sun is coming in, it looks different than when the curtains are closed or at night when the lights are on."

With a $1 million grant in 2020 from the National Institute of Justice, the Exchange Initiative improved the app and the computer models, enhancing the ability to examine details of the room, such as a lamp or desk.

"Every Motel 6 in the country has been renovated to be exactly the same," Stylianou said. "So if there's a unique scratch mark on a lamp, that can be important. ... Often, in the [victim] pictures, you only see one object in the image, just a picture on the wall or just the carpet, and then the AI doesn't work as well. So now, we ask for pictures of specific objects and have been building models to work on those."

That could be critical leading up to Feb. 12, when the Super Bowl is held in Glendale, Arizona. For weeks, Theresa Flores, program director for U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking and founder of the SOAP (Save Our Adolescents from Prostitution) Project, has been there, training people to recognize the signs of trafficking, which can increase dramatically during large sporting events.

While the database can in theory be used to locate and rescue a victim, most often, the perpetrators are long gone before law enforcement can arrive. Instead, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children uses it to assist law enforcement in investigations. Where photos of victims were taken can be important evidence in criminal cases against perpetrators.

Because of this, officials at the Exchange Initiative do not know how many victims have been rescued or traffickers prosecuted, but officials at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children tell them the database is used daily and has been successful in locating victims and prosecuting traffickers.

"It's clearly working if we've gotten these grants," Ritter said.

Advertisement

Nix also recently did a live demonstration with the FBI's cyber-crime division, where they ran an FBI photo through the database to correctly pinpoint a specific hotel.

Sr. Anne Victory, a member of the Sisters of the Humility of Mary and a board member for U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking, said the TraffickCam app is a valuable tool for law enforcement that also raises awareness of human trafficking and provides people with a way to help stop it.

"It's a hidden crime. It's generally not reported," Victory said. "Victims don't tend to come forward easily because they're frightened — and with good reason."

Stylianou said the database and the AI that uses it are powerful tools. The Exchange Initiative does not want them abused, so they are working on how to make the information more accessible to law enforcement without opening up the possibility that, say, an aggrieved partner could use it to locate an ex in hiding.

Abby Stylianou, then a graduate student in computer vision and machine learning at Washington University in St. Louis, created the TraffickCam system to find victims of human trafficking. (Photo provided by Washington University)

Currently, very few people have access, and those running the database monitor every query. Although international law enforcement agencies have contacted Stylianou directly, most database use is domestic, and almost all of it is funneled through the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Because of those concerns and others, such as protecting the identities of victims of sex crimes, the database specifically does not do facial recognition. And Stylianou knows the information they provide is just one piece of a criminal case.

But she marvels at the Catholic sisters who inspired the project, provided the initial funding, and helped test the app.

"It's really been an extraordinary experience to have [sisters'] support," Stylianou said. "We could not have done this without the support of the sisters."

Ritter, too, gives all the credit to sisters.

"We're just meeting planners," she said. "But the Catholic sisters, their impact is so vast. They stand up, and they stand firm. When they're standing for or with someone, you cannot lose."