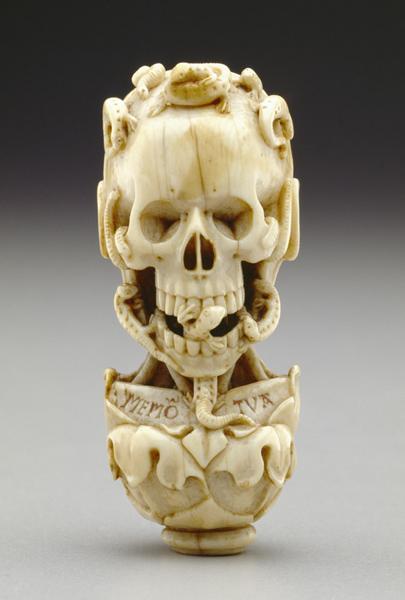

Pendant, memento mori from a chaplet, ivory, circa 1520-1530, northern France or southern Netherlands (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

Visual clues and ominous signposts are easily overlooked in 17th-century Dutch vanitas paintings, which feature massive, palatable displays. Every detail of the lavish food arrangements is delineated carefully, but abundance here foreshadows decay, echoing biblical passages. Having amassed cattle, money, houses, vineyards, gardens and "every sort of fruit trees," Ecclesiastes realizes that currency is counterfeit. "All that my eyes sought, I didn't deny them. I withheld no joy from my heart," he reports. Yet, all proved vanity and worthlessness, and "there is no profit under the sun."

Against this biblical backdrop, as well as other religious and humanist texts emphasizing the fleeting aspects of earthly life, a genre of art arose to prominence in the Middle Ages called "memento mori," a Latin admonition to remember that everyone must die. An exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, titled "The Ivory Mirror: The Art of Mortality in Renaissance Europe" (through Nov. 26), focuses on memento mori objects made around the year 1500. And although many illustrate moral values, they also cannot be considered wholly outside theology.

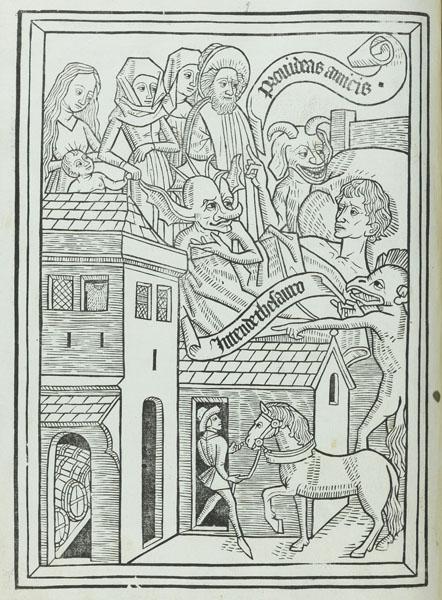

"The Temptation of Avarice," from "Ars Moriendi," a block book published by Nicholas Gotz, 1466, Cologne, Germany (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

Two pages from the 1466 German book Ars Moriendi ("The Art of Dying Well"), from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, appear in the show. In one, "there is this guy on his deathbed surrounded by the goathead demon, the Yoda demon, and the bird demon," explained Stephen Perkinson, associate professor of art history at Bowdoin and exhibit curator.

The evocative demons instruct the man, via speech scrolls, to look to his wine cellar, servants, and horses — all depicted. "Think of your treasures," one says. "Provide for your friends." The demon even gestures toward the man's family and friends — just the sort of entourage one would want today around one's deathbed. In the Middle Ages, death was omnipresent, and it was typical to die at home surrounded by loved ones.

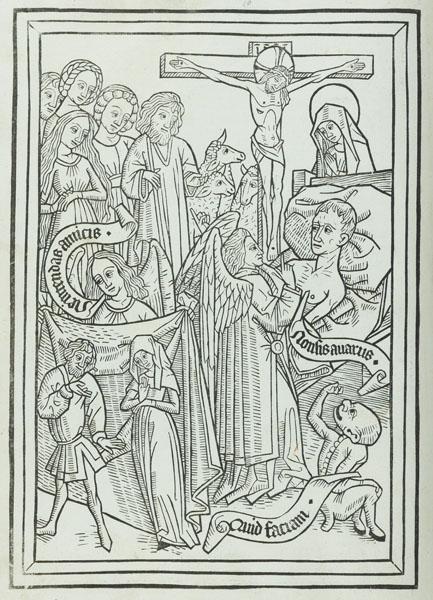

But this 15th-century book associates dying well with avoiding the avarice, or greed, of willing belongings to family and friends. In a second illustration, an angel tells the dying man, "Put completely behind you all earthly things, whose memory in any event cannot bring you salvation and is a great obstacle." The exhortation, Perkinson writes in the catalog, is to emulate Christ's "voluntary poverty." A second angel, in fact, has lifted a curtain to prevent the dying man from seeing his entourage, stating, "Do not concern yourself with your friends."

"The Angel’s Counsel against Avarice," from "Ars Moriendi," a block book published by Nicholas Gotz, 1466, Cologne, Germany (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

So traumatic is this exchange to a lurking demon that the demon whines, "What shall I do?" He's right to worry, as he is competing with formidable foes: No less than the Virgin Mary and the crucified Christ look down from the top right of the picture.

"The gist there is thinking from the church's point of view that they are hoping to ensure that a significant portion of what you leave behind goes to church and charitable activities and not just to family," Perkinson explained.

As tricky artistic symbolism has gone, so has understanding the book of Ecclesiastes, which can read as a very nihilistic text. In the Middle Ages, St. Jerome's contemptus mundi ("contempt for the world") reading prevailed, said Dan Treier, professor of theology at Wheaton College and author of the 2011 book Proverbs and Ecclesiastes.

To Jerome, Ecclesiastes weaned readers off of worldly trappings toward "asceticism, even monastic withdrawal," Treier said. "Martin Luther prominently opposed this reading at the dawn of the Protestant Reformation, anticipating modern readings." If Ecclesiastes tries out a skeptical worldview, "the memento mori theme readily becomes a kind of realistic resignation before an inscrutable and almost despotic deity," said Treier, who subscribes to a more positive, "theologically friendly" reading of the text, in the context that "our labor in the Lord is not in vain."

"Ecclesiastes is looking for this brighter light, urging us to remember our creator while we are young, to enjoy the gifts of creation while remembering that we will die and face judgment," he said. "Ecclesiastes anticipates some kind of future that will make it worthwhile to remember our creator; it just can't see 'under the sun' what that future is."

Craig Bartholomew, professor of philosophy, religion and theology at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario, also rejects Jerome's reading of the work, which neither John Calvin nor Huldrych Zwingli wrote commentaries upon.

"Nevertheless it has been influential," Bartholomew said. "Jerome's contemptus mundi interpretation dominated for some 1,000 years." It took Lutheran reformers, with strong doctrines of creation and vocation, to "break the back of Jerome's — in my view incorrect — reading," he said. "I think a key element in memento mori is that Christians could focus on this, because they were sure it was not the end but the beginning of a new and eternal life."

But death, of course, wasn't suddenly discovered in Second Temple-era Judaism. Rather, according to Brown, there was distress at the time surrounding the "morbidity upon the individual," which had reached "unprecedented heights" in that ancient culture.

Pendant to a rosary or chaplet, ivory with traces of polychromy, attributed to Chicart Bailly, circa 1500-1530, thought to be created in Paris (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

Morbidity surfaces often in the memento mori works at Bowdoin, including ivory beads — perhaps for prayer — that depict skulls. Certain materials appealed in the Middle Ages for uses apparently intended by God.

"In the case of ivory, it said, 'Make me into something that is bone,' " Perkinson said of the skulls. The 13th and 14th centuries, he added, were periods of great Gothic ivories, including crucifixions. Those too drew upon the properties of the medium.

"If you hold it, it begins to take on body heat. So you're holding a little figurine of the virgin, and she seems to be coming alive in response, that's very appealing," he said.

A circa 1530 rosary with elephant ivory beads in the collection of London's Victoria and Albert Museum, which appears in the exhibit, contains a mid-19th-century insertion, a forgery, in the top piece, but the rest of the three-faced beads are authentic.

"They give you examples of people of different walks of life, kind of a cross section of medieval society," Perkinson said. Turning the biggest bead, the handler sees a young man in the flush of life wearing a laurel wreath — signaling an earthly victory — then a very elegantly coiffed woman and, finally and unexpectedly, a skull.

"Death is wearing the man's laurels," Perkinson said. "Death is the leveler. It erases social distinction."

Advertisement

And as with Ecclesiastes, what comes off to modern eyes as medieval, dark, morbid and moralizing would have been meant at the time to get people thinking and reacting in different ways. Memento mori objects were largely owned by aristocrats — arguably those who most needed the reminder of their mortality — but powerful bishops, particularly those with wealthy upbringings, also owned the objects. And these ivory reminders of how transient wealth is would, of course, have cost a pretty penny.

Pendant, memento mori from a chaplet, ivory, circa 1520-1530, northern France or southern Netherlands (Bowdoin College Museum of Art)

And as remote as memento mori objects can seem, they retain contemporary relevance. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bohemian princess Bonne of Luxembourg's early 14th-century prayer book shows the legend of the "three living and three dead," said Barbara Boehm, senior curator for the Met Cloisters. Three princely hunters suddenly find themselves face-to-skull with their own skeletons in the work.

"The best memento mori images stop us in our tracks, just like the three privileged hunters of the manuscript, and cause us to think about what we are doing with our lives, what kind of legacy we will leave," Boehm said.

And the Cloisters manuscript is particularly poignant, as the princess would have become the French queen if she hadn't died, in her mid-30s, of the plague.

"A princess who would have become queen, dying tragically in her 30s? That's a story from our own time," she said.

[Menachem Wecker is the co-author of Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education.]